New climate report paints harsh picture for future of Canada's coastlines

Time is of the essence to prevent the worst effects of climate change for Canada's coastal communities

The year is 2050.

The remaining residents of Amherst, Nova Scotia - those that haven't yet packed up and moved away - are once again picking up the pieces and drying out after the waters of the Bay of Fundy topped the local dikes and flooded the small coastal community.

Even two decades ago, locals were concerned about the 'perfect storm' coming along, right at high tide, to cause the bay waters to flow over their existing protections. Now, with Bay water levels at their highest point ever as a result of unchecked climate change, it's not a 'perfect storm' that raises anxiety levels. Instead, any high tide is cause for concern, and the yearly king tides mean days of preparation and potential evacuations.

Indeed, everywhere in the province, coastal communities have been dealing with rising waters and increasing storm surge risks. Extreme flooding events only seen once every 100 years in the past are happening at least once a year, if not more, for over a decade.

Meanwhile, up and down the Atlantic coastline, fishing boats are again reporting disappointing catches. This isn't about limits imposed by the government, even those have been around for decades, to prevent overfishing. This is different. The populations just aren't there anymore. The news from Greenland fisheries is more encouraging, but around Atlantic Canada, even the traditional stocks have dwindled, noticeably.

Atlantic herring out of the St. Lawrence seaway is no longer a reliable source of income. Word is they migrated farther north. Any lobsters that are pulled from the water are tiny, thin-shelled specimens compared to what was caught just a few decades ago. It's extremely rare to find any lobsters that are above the maximum allowed size - the so-called 'jumbos' that were thrown back to protect the breeding stock. More than half don't even meet the minimum size requirements to keep.

In British Columbia, Vancouver's forward-thinking policies have undoubtedly saved the city from many potential flooding events due to sea-level rise. Other communities along the west coast have not been as fortunate, however. The frequency of extreme events has been on the rise, with already five 'once-in-a-century' floods recorded in the past three decades, and three of those in just the past ten years, alone. Scientists are projecting, with ever-increasing confidence, that it will only take another twenty years for them to become a yearly problem!

Fisheries up and down the B.C. coast have been dealing with hit-or-miss seasons for years now. Rising ocean temperatures, increasing acidity, and decreased oxygen content are taking even greater tolls on marine life.

In the Canadian Arctic, issues like sea-level rise and extreme flooding events haven't become a major issue yet. Communities there have been suffering through their own problems, stemming from sea ice loss and the permafrost melting beneath their feet, their buildings and the limited infrastructure in place that far north.

BACK TO THE PRESENT

The above is a view of one potential future for Canada's coastal communities, based on the newly released Special Report on the Ocean and Cryosphere in a Changing Climate (SROCC) report from the U.N.'s Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC).

In the report, more than 100 scientists from over 30 countries around the world scoured through the latest scientific knowledge about how climate change is impacting ocean, coastal, polar and mountain ecosystems, and the impacts on the human communities that depend on these ecosystems.

What they found after compiling all this collected knowledge is alarming.

"The world's ocean and cryosphere have been 'taking the heat' from climate change for decades, and consequences for nature and humanity are sweeping and severe," Ko Barrett, Vice-Chair of the IPCC, said in a press release on Wednesday. "The rapid changes to the ocean and the frozen parts of our planet are forcing people from coastal cities to remote Arctic communities to fundamentally alter their ways of life."

"By understanding the causes of these changes and the resulting impacts, and by evaluating options that are available, we can strengthen our ability to adapt,” she said. "The Special Report on the Ocean and Cryosphere in a Changing Climate provides the knowledge that facilitates these kinds of decisions.”

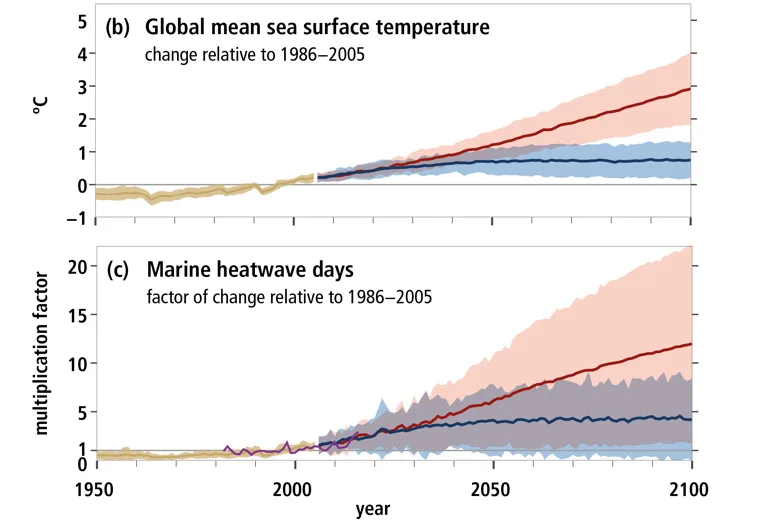

Ocean temperatures have been rising, unabated since 1970, and the rate of warming has likely doubled since the early 1990s, the report states. Marine heatwaves - periods of extremely high ocean temperatures - have not only become more intense, but the last 40 years have seen them doubling in frequency.

Adapted from Past and future changes in the ocean and cryosphere graphic, SROCC report Summary for Policy Makers, pg SPM-6. These two graphs show ocean temperature rise and the occurrence of marine heatwaves. The brown line is past changes. The blue and red lines, along with their range of impacts, represent the changes going forward, under the best-case scenario and the worst-case, respectively. Credit: IPCC

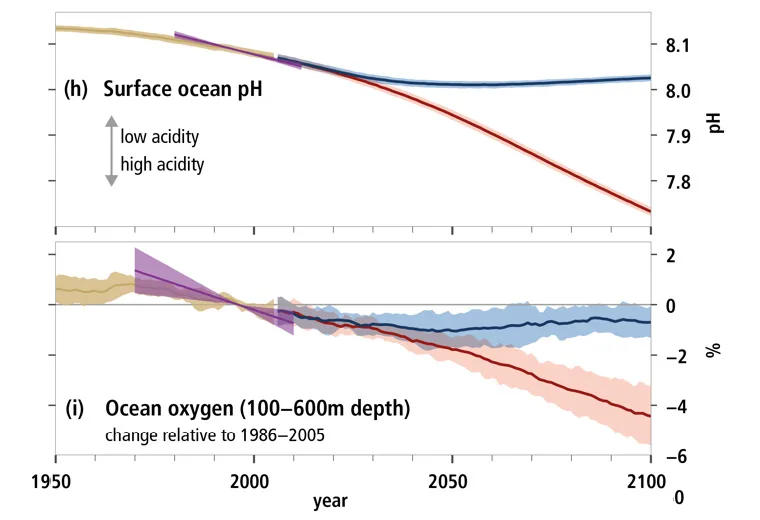

The surface levels of the ocean are becoming more acidic as they absorb more carbon dioxide, putting the survival of some marine life species at risk. There are also signs that oxygen levels in the water - critical for the survival of all marine lifeforms - are dropping as well.

Adapted from Past and future changes in the ocean and cryosphere graphic, SROCC report Summary for Policy Makers, pg SPM-6. These two graphs show the changes in both acidity (pH) and oxygen concentration in the water. The brown line is past changes based on models, while the purple is observations. The blue and red lines, along with their range of impacts, represent the changes going forward, under the best-case scenario and the worst-case, respectively. Credit: IPCC

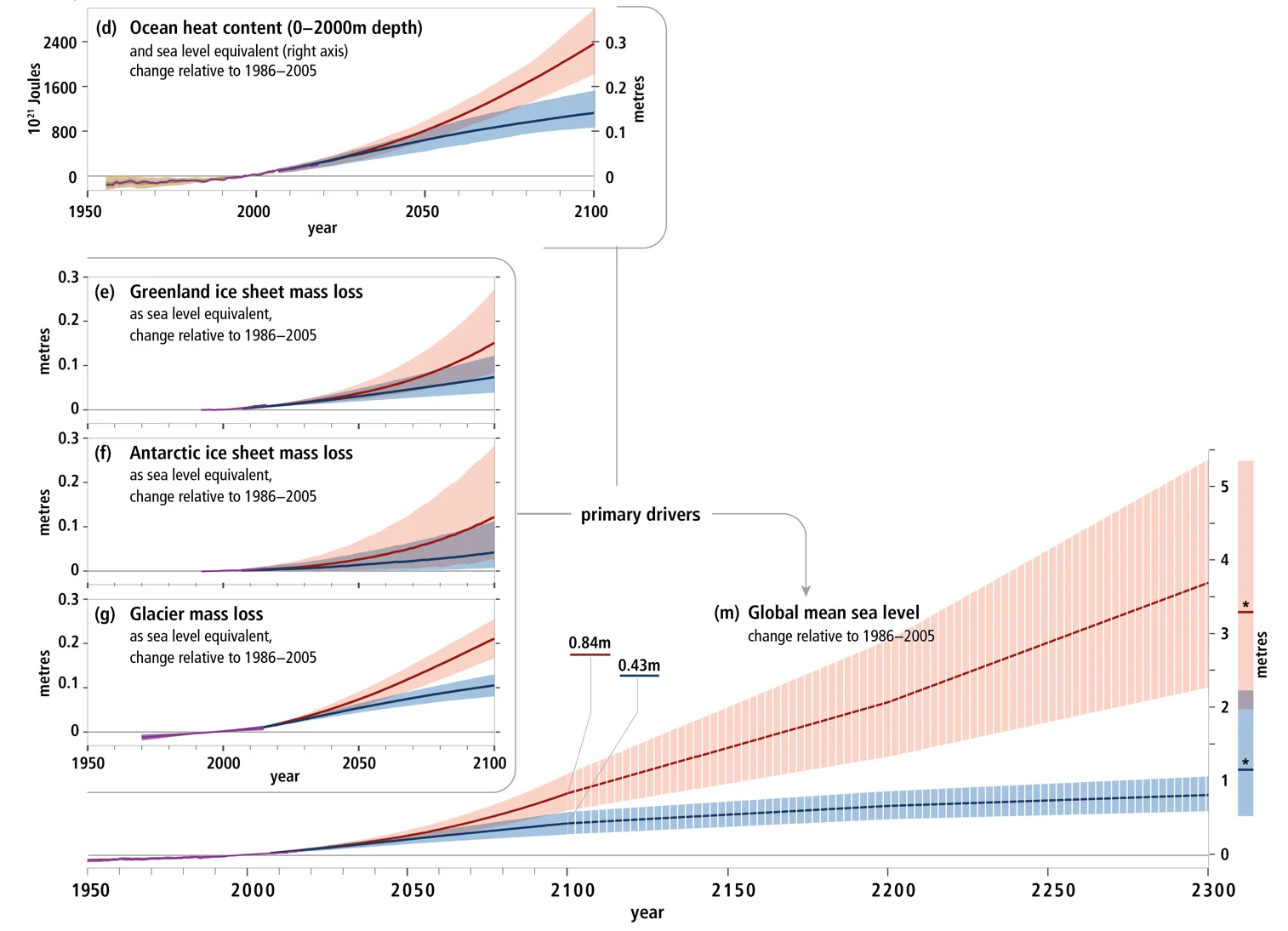

Additionally, ocean water levels have been rising steadily for decades, partially due to the addition of more water from melting glaciers and polar ice sheets, and partly due to thermal expansion of the ocean water.

Adapted from Past and future changes in the ocean and cryosphere graphic, SROCC report Summary for Policy Makers, pg SPM-6. The graphs show ocean heat content, plus the changes in ice sheet mass and glacier mass, globally, as contributors to sea-level rise. The brown line is past changes based on models, while the purple is observations. The blue and red lines, along with their range of impacts, represent the changes going forward, under the best-case scenario and the worst-case, respectively. Credit: IPCC

All of the above graphs reveal the changes we are already seeing in our oceans and the cryosphere.

Based on the best scientific projections available, these graphs also provide a look going forward, to what is likely to come, based on two different scenarios.

The blue lines, and their associated range (the shaded part), show the best-case 'RCP2.6' low emission scenario. This is the path forward that would limit global warming to just 2°C above pre-industrial levels, and limit global sea-level rise to an average of less than half a metre, by the year 2100.

In this possible future, we take strong, decisive actions now to halt the burning of fossil fuels and transition the world over to clean, renewable sources of energy. In this case, there are still impacts to come from the greenhouse gases that have already been emitted into the atmosphere. It is generally thought, though, that these are impacts our civilization can adapt to, with some effort.

The red lines and their associated range of uncertainties, on the other hand, are the worse case, 'RCP8.5' high emission scenario. In this future, global temperatures likely reach over 4°C by 2100, with ocean levels rising by nearly one metre.

These lines reveal the dire consequences if we continue on, business as usual, with our coastal communities likely suffering results similar to the fictional account presented at the top of the article.

In this case, there are substantial risks that human civilization will reach the limits of its ability to adapt to the changes taking place, likely guaranteeing disastrous consequences.

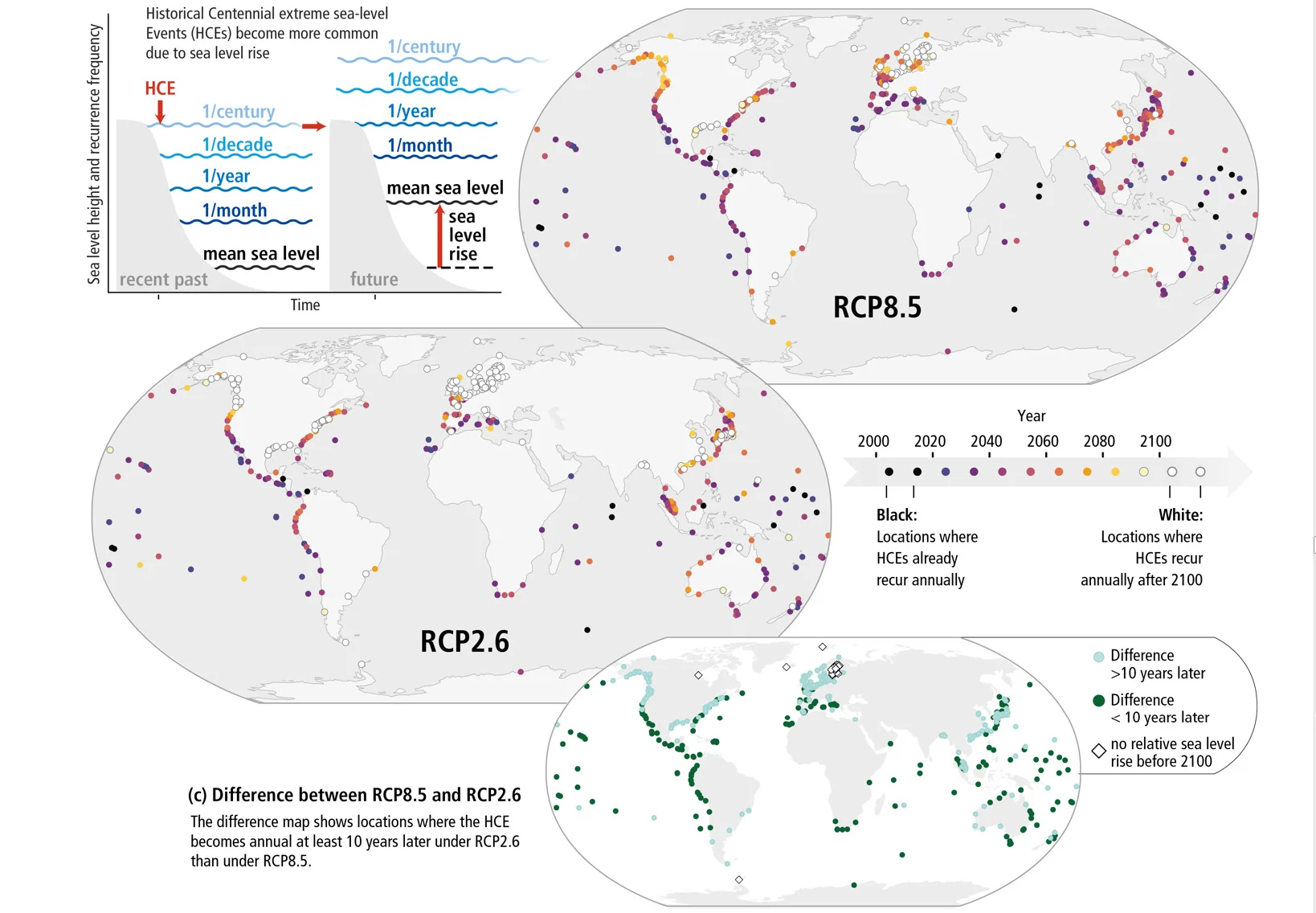

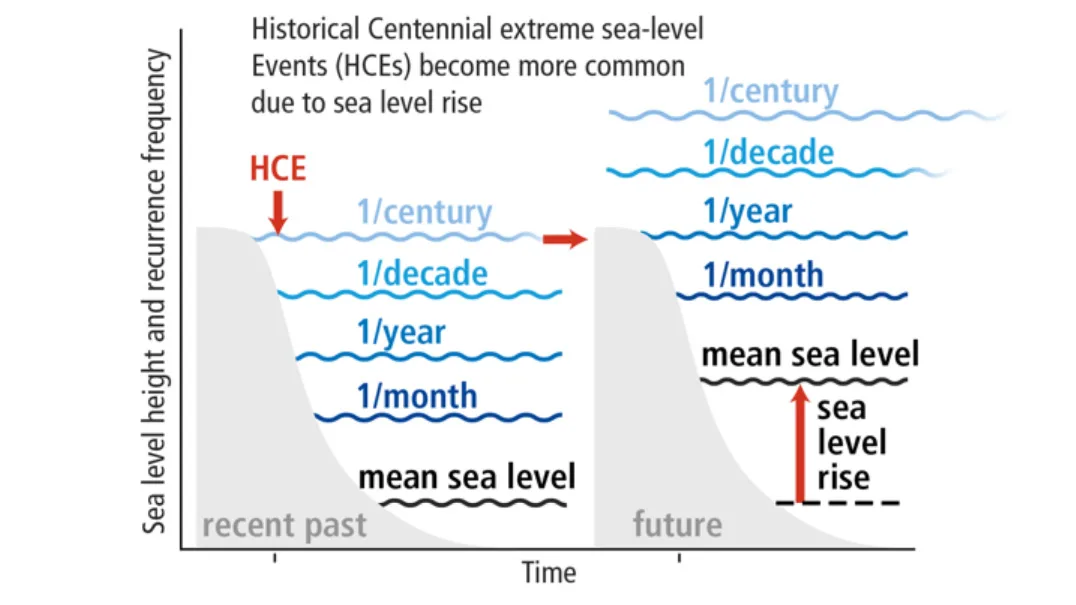

One area given special attention in this report was the occurrence of extreme sea-level events. These are events where local sea level rises significantly, due to the combination of sea-level rise, tides, and the impacts of weather, such as with storm surge.

Figure SMP.4, Extreme sea level events, from SROCC report Summary for Policy Makers, pg SPM-33. Credit: IPCC

Under global warming, these extreme sea-level events, which occurred only once per century in the past, are projected to increase in frequency, so that they happen yearly!

In many regions of the world, marked with coloured dots on the maps above, this transition is inevitable. It is merely a matter of time, with the darker the dot colour, the sooner we can expect this shift to yearly extreme events.

A close-up view of the effect of regional sea-level rise on projected extreme sea-level events, from the graphic above. Credit: IPCC

This special report is the third in a series, following up on the Global Warming of 1.5°C report released nearly a year ago, and the Land and Climate Change from earlier this year.

This U.N. report adds significant weight to the findings of the Canada's Changing Climate report, released by the federal government earlier this year.

"We will only be able to keep global warming to well below 2°C above pre-industrial levels if we affect unprecedented transitions in all aspects of society, including energy, land and ecosystems, urban and infrastructure as well as industry. The ambitious climate policies and emissions reductions required to deliver the Paris Agreement will also protect the ocean and cryosphere – and ultimately sustain all life on Earth," Dr. Debra Roberts, head of the Sustainable and Resilient City Initiatives Unit in eThekwini Municipality in Durban, South Africa, and co-chair of IPCC Working Group II, said during a press conference on Wednesday.

"The more decisively and the earlier we act, the more able we will be to address unavoidable changes, manage risks, improve our lives and achieve sustainability for ecosystems and people around the world - today and in the future," Roberts concluded.

Source: IPCC