New law gives feds ‘explicit power’ to investigate toxins in tailings ponds

New changes to the Canadian Environmental Act spell out the federal environment minister’s role in gathering and reporting info on toxic oilsands tailings ponds.

Just one mention of tailings ponds in the recent update to the Canadian Environmental Protection Act (CEPA) could mean more accountability for oil and gas companies, according to experts.

Bill S-5, often called the first substantive update to Canada’s core environmental protection regulation in decades, now specifically states the federal environment minister may request and collect data about tailings ponds. The bill received royal assent on June 13.

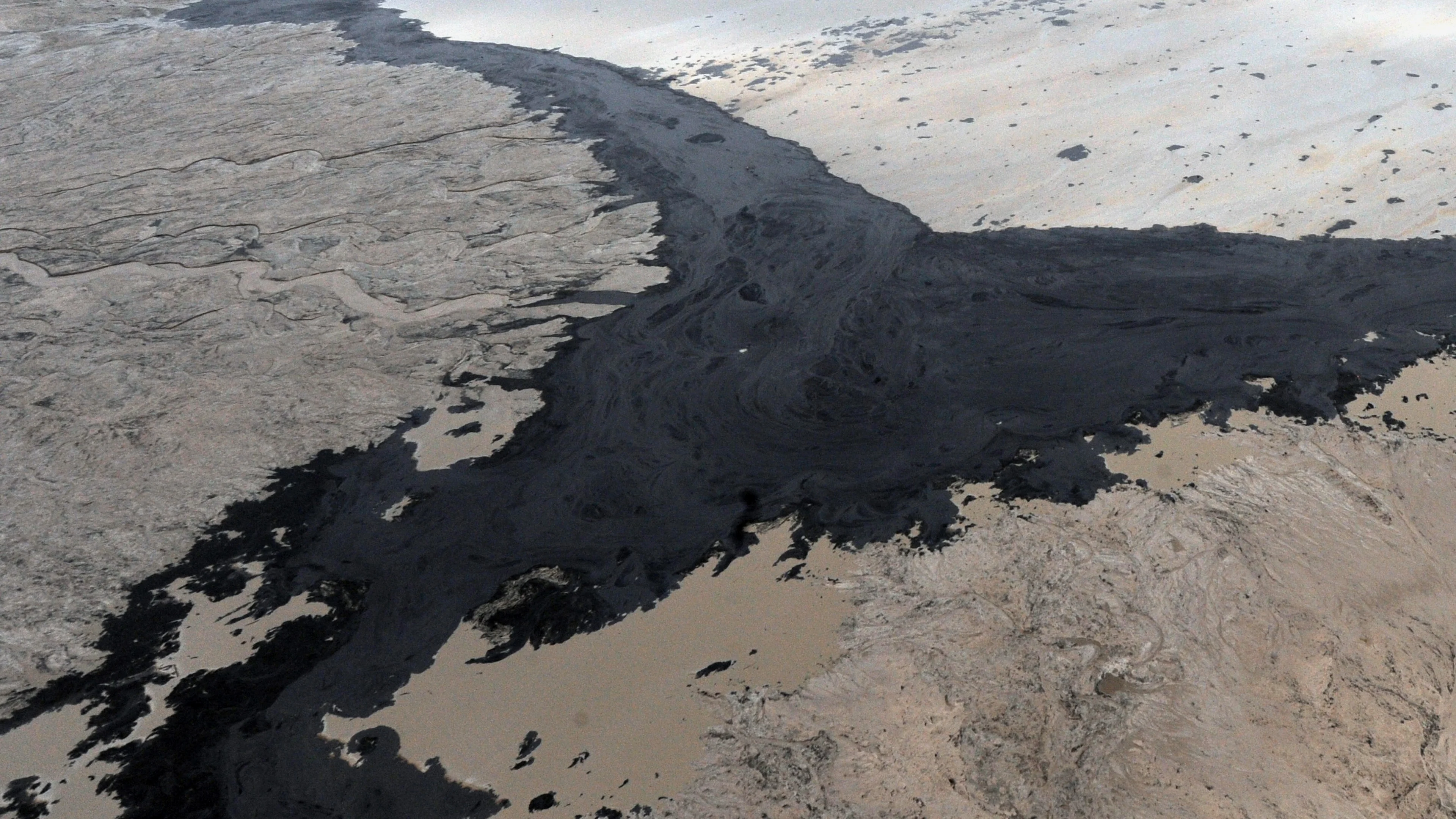

Tailings ponds are reservoirs of water and toxic byproduct chemicals from oil and gas extraction, as well as mining operations. In fact, they’re often more like tailings lakes, as some of them are kilometres long. According to Environmental Defence Canada, there are 1.8 trillion litres of tailings waters in Canada, spread across a surface area larger than Vancouver.

Sometimes, tailings ponds will leak, spewing potentially harmful chemicals into natural waterways. Nearly a decade ago, a leak from a mining tailings pond at Mount Polley, B.C., caused ecological devastation in the area. And more recently, Indigenous and environmental groups have sounded the alarm over leaks at fossil fuel operations in Alberta.

READ MORE: Canada opens formal investigation into Imperial's oilsands tailings leak

This new bill adds tailings ponds to a part of the 1999 version of the CEPA, which enables the federal minister to collect information for various purposes, including creating an inventory of data, guidelines, codes of practice, reporting, or assessments.

Green waste water pours into a tailing pond at the Syncrude open pit oil excavation mine in Fort McMurray in 2009. The tailing ponds are areas of refused mining tailings. They are a huge problem for the tar sand industry, as they contain toxic chemicals and waste water, and take much longer to settle than projected. They are also a eye-sore, a tell-tale to how dirty the tar sand industry is. (Orjan F. Ellingvag/Dagens Naringsliv/Corbis via Getty Images)

Experts told The Weather Network this addition could compel the federal environment minister to take more action on tailings ponds leaks. However, they also say there’s room for improvement in how Canada deals with the ponds and what fills them.

Lisa Gue, manager of national policy with The Suzuki Foundation, told The Weather Network she was happy to see CEPA strengthened through Bill S-5. She said that, while the federal minister could previously also request tailings ponds information from oil and gas operators, their mention in the bill confirms and specifies the federal environment minister’s authority to collect it.

“Obtaining information is often the first step towards … assessing environmental risks, obviously, and all sorts of decision making,” she said.

“We're very eager to see how the federal minister uses this new newly confirmed authority,”

‘Get the ball rolling’

Gue added the bill could result in stronger regulations on tailings ponds. The data would also enable the federal government to create and “fine tune” future regulations. A good first step would be for the minister to collect data on the types of contaminants in tailings ponds, and assess them for risk, she explained.

“We would certainly like to see the federal minister use this authority to get the ball rolling … by requesting the information needed to better characterize the risk from tailings,” she said.

Alienor Rougeot, climate and energy program manager at Environmental Defence Canada, reiterated the inclusion in Bill S-5 would “reaffirm” a level of federal jurisdiction over things like tailings leaks.

Earlier this year, it was announced that tailings from Imperial Oil’s Kearl mine operation had been leaking for months — a lengthy process that eventually prompted a federal investigation.

At the time, some impacted Indigenous groups placed the blame on the Alberta Energy Regulator (AER) for failing to report the massive leaks. However, Ottawa also received criticism.

Meanwhile, the AER has been criticized for its particularly light touch in regulating the province’s fossil fuel industry.

“Having the minister having an explicit power to be able to gather information might be able to cut through some of that,” Rougeot told The Weather Network.

Similarly, oil companies are receiving government funding to clean up their tailings ponds, but there’s limited public information about how this would play out, according to Rougeot. (Imperial Oil has also started the process of cleaning up its recent tailings leak.) In theory, the government now has a clearer opportunity to gather information on these clean up plans, she added.

An aerial view of a tailings pond at the Suncor oilsands mine near the town of Fort McMurray, Alta., on Oct. 23, 2009. (Mark Ralston/AFP via Getty Images)

The AER declined to do an interview on the topic. But Benji Smith, press secretary to Alberta’s Minister of Environment and Protected Areas, replied to The Weather Network with an emailed response stating “Alberta’s government is strongly committed to the responsible management of tailings, progressive reclamation of the oilsands, and credible environmental monitoring.”

The ministry is in the process of reviewing the changes to CEPA to determine how it will impact Albertans, according to Smith’s email. He added that tailings ponds, along with other Alberta Energy industry activities, are “already the subject of comprehensive, credible, and transparent environmental monitoring, and rigorous regulatory oversight and enforcement, at both the provincial and federal levels.”

According to Neil Craik, a professor of law with the University of Waterloo and the director of the School of Environment, Enterprise and Development, climate is a shared jurisdiction of both the federal and provincial governments. However, in recent years, there have been several court battles between both levels of government about which one gets to regulate different parts of the climate (Alberta’s efforts to curtail the federal Impact Assessment Act, for instance).

The new regulations are “perhaps signaling that the government is in the future going to look more closely at tailings ponds as a subject of federal regulation,” Craik told The Weather Network.

‘Indirect ways’ of taking action

According to Rougeot, there’s still room for improvement. One case would be through regulating toxic naphthenic acids in tailings ponds.

Around five years ago, the federal government performed a risk assessment through CEPA on a classification of chemicals called naphthenic acids. However, this assessment focused solely on naphthenic acids in consumer goods, rather than in tailings ponds.

Rougeot said these are some of the most toxic chemicals in tailings waters and the federal environment minister should perform a risk assessment and create a risk management plan for tailings ponds naphthenic acids through CEPA now. While Rugeot said she was happy to see an explicit mention of tailings ponds in the bill, it’s “really the bare minimum, and really far from what we need.”

The mention of tailings ponds is just one part of a larger update to CEPA. For instance, Bill S-5 includes provisions about the cumulative effects of pollutants, impacts on marginalized communities, and commits to implementing the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples. Perhaps one of the most notable additions is the right to a healthy environment.

According to Craik, in theory, the right to a healthy environment could apply to climate change and emissions. Citizens would not be able to levy lawsuits against, for example, an oil and gas company because of this. Rather, the provision will impact government decisions surrounding its environmental policies and, in theory, gives private citizens legal recourse against the federal government for when it doesn’t exercise the proper discretion, he said.

This means there’s a “higher burden of justification” for the government when it makes decisions related to CEPA. And the bill may, as such, put extra pressure on the feds because, if citizens feel they aren’t being sufficiently protected, the government policies may end up getting challenged.

However, he noted the wording of the law gives the government “a fair amount of leeway” in terms of interpretation. The new regulations include the right to a healthy environment, but this is balanced against several other factors, he said, including health, scientific and economic ones.

He added the part on cumulative effects could also apply to climate change. Even prior to Bill S-5, carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gasses were regulated by CEPA. According to Craik, it’s not that CO2 or various other greenhouse gasses are particularly toxic, especially in small amounts.

But, the cumulative effects of their release can impact the environment.

“I think that there's a number of indirect ways in which [these] changes may impact how the government addresses climate issues in the future,” he said.

WATCH BELOW: Digging deeper into greenhouse gas reporting with Steven Guilbeault

Thumbnail image: A crude scarecrow is used to thwart birds from landing in the oil residue floating on top of a tailings pond at the Syncrude oil processing facility. (Getty Images)