Wildfire smoke may pose risk for brain health

Wildfires have burned more than 100,000 square kilometres of Canada’s forests in 2023 so far — roughly the size of Newfoundland.

The wildfires have burned four times as much land as the average wildfire season in this country. The ash, smoke, and other pollutants released by the fires spread over parts of North America and far across the Atlantic, even darkening skies in mainland Europe on occasion.

When people breathe in wildfire smoke, the small particles — called fine particulate matter — don’t just stay in the lungs. The fine particulate matter is absorbed in the bloodstream and can reach the brain. There is emerging evidence linking exposure to forgetfulness, trouble focusing, brain fog, and even dementia. Some researchers worry that human-caused climate change may intensify these forest fires in the future.

"We are currently living through devastating wildfires across the country during one of the worst wildfire seasons on record,” said Jean-Yves Duclos, Canada’s former minister of health, in a statement. “During these times, we should all take the necessary actions to protect our health and well-being, including knowing the air quality in our communities and reducing exposure to wildfire smoke."

Visit The Weather Network's wildfire hub to keep up with the latest on the active start to wildfire season across Canada.

How does wildfire smoke affect the brain?

According to Gould, the small particulate matter in wildfire smoke is so small that it can bypass the brain’s first line of defense: the blood-brain barrier. While this structure prevents large toxic compounds from entering the brain, the fine particulate matter is small enough to sneak through the defenses. Gould explained these pollutants can cause inflammation and oxidative stress on the brain.

“Growing evidence posits a connection between air pollution and other outcomes related to brain health,” said Carlos F. Gould, an assistant professor at the University of California in San Diego who studies the links between air pollution and health. “These include impacts on dementia, cognitive performance, and productivity.”

However, he cautioned that scientists aren’t yet able to say that wildfire smoke directly causes poor cognitive performance or dementia.

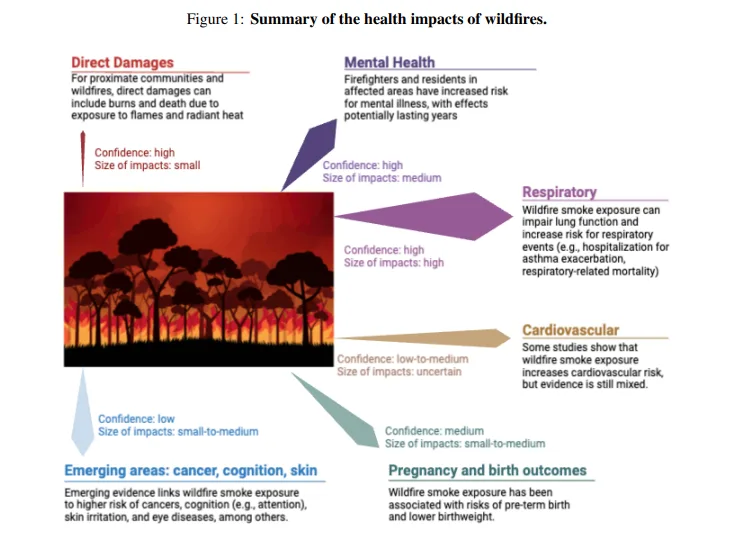

The literature on wildfire smoke’s impacts on respiratory conditions is particularly rich, showing increased respiratory-related mortality, increased respiratory-related hospitalizations and emergency visits, declines in lung function, the exacerbation of chronic respiratory conditions and asthma, and more ambulance dispatches. (Health effects of wildfires study)

For his part in the research, Gould recently released a preprint — which is currently being peer-reviewed for publication by a scientific journal — summarizing what scientists know about the health effects of wildfire smoke. To date, many of the studies looking at wildfire smoke focused on its effects on the heart and lungs.

SEE ALSO: Does breathing in wildfire smoke mean lung issues for life?

Nonetheless, studies have shown people who are exposed to more small particulate matter as a result of wildfire smoke perform worse on academic tests and laboratory measures of memory, thinking, and attention. People who live in areas that are exposed to more fine particulate matter are more likely to have a stroke and more likely to be diagnosed with dementia.

“While individual level changes in risks may be small, population-level effects could be large,” Gould said.

If the chances of an older individual developing dementia in a given year is one per cent, a five per cent increase in risk may be negligible. In a larger population, this means substantially more cases of dementia.

Future research

The Weather Network asked Health Canada if they have more information on the impact of wildfire smoke on memory, cognition, or brain health. Tammy Jarbeau, a senior media relations advisor, provided a link to a Health Canada press release about the wildfires and other official sources of information. These resources did not mention these potential risks.

Researchers say human-caused climate change will increase the conditions for wildfires to ignite and spread, as well as their intensity, in the future. What does this mean for the brain?

“It seems likely that an increase in wildfire activity will also lead to more widespread negative impacts on brain health,” Gould said. “Only a limited number of studies have credibly attributed changes in health to changes in wildfire smoke.”

Right now, scientists don’t have the data to say whether these wildfire pollutants will have the same impact as similar-sized particles released by other sources like gas-guzzling cars. But thanks to recent technological advancements, it has now become possible for researchers to measure the levels of fine particulate matter released specifically by wildfires. This will allow scientists in the future to better estimate the risk that wildfire smoke poses to brain health.

“Addressing the health impacts of wildfires begins with the upstream determinants of wildfire activity,” Gould wrote in the preprint. “Broadly speaking, the recent increase in wildfire activity in North America has been driven by the combined effect of a century of fire suppression that left an accumulation of fuels, a warming climate that has made these fuels drier and more flammable, and increased human activity in the wildland-urban interface that have made ignitions more likely.”

In the meantime, Health Canada advised people to pay attention to the Air Quality Health Index and any special air quality statements that are released by Weather Canada. People who have chronic health conditions, like diabetes, might be at a higher risk of complications from wildfire smoke. Individuals should drink lots of water, limit their exercise and how much time they spend outside. Outside, a high quality air respirator can help filter out some of the pollutants in wildfire smoke.

WATCH BELOW: How wildfires can increase flood risk and impact water supply

Thumbnail image: The Eagle Bluffs Wildfire burns behind a home after it crossed the Canada-U.S. border from the state of Washington and prompted evacuation orders in Osoyoos, B.C., on July 30. (Jesse Winter/REUTERS)