90% of humans are exposed to air pollution that exceeds safety guidelines

Each year over four million people die prematurely due to PM2.5 exposure.

A study published by researchers from Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) reports more than 90 per cent of the global population is exposed to average annual concentrations of pollutants that exceed the air quality guidelines set by the World Health Organization (WHO).

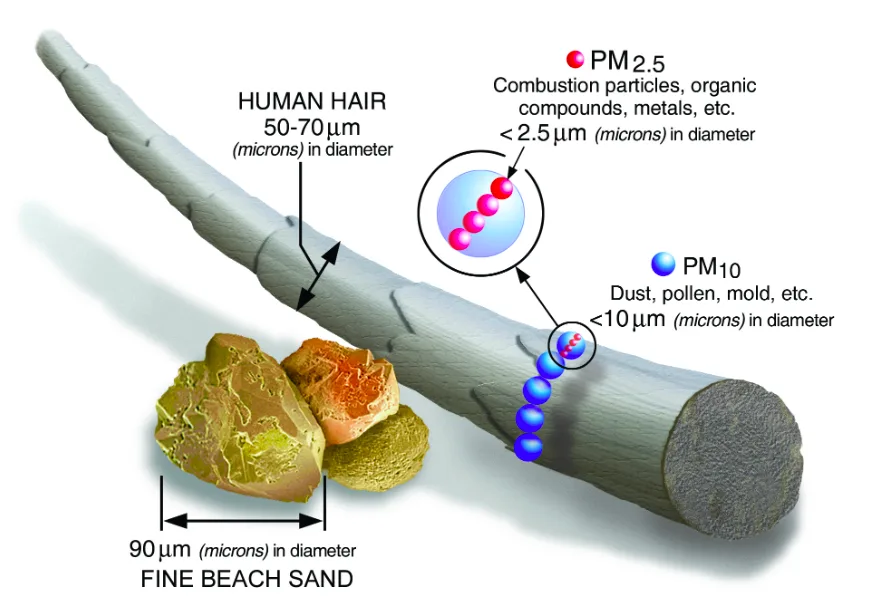

The study focused on the specific pollutant called PM2.5, which has a maximum diameter of 2.5 micrometres. This tiny size concerns scientists because it is small enough to enter our bloodstream and lungs where it can then cause respiratory and cardiovascular complications.

PM2.5 has a diameter of 2.5 micrometers or less whereas the average human hair is approximately 70 micrometers in diameter. (United States Environmental Protection Agency)

According to research from McGill University, approximately 4.2 million people prematurely die each year from inhaling PM2.5. This includes one million deaths in China, over 500,000 in India, nearly 200,000 in Europe, over 50,000 in the United States, and about 5,900 in Canada.

The growing body of evidence that confirms the dangerous and potentially fatal outcomes of PM2.5 prompted WHO to update its air quality guidelines. The changes, released in September 2021, include a 50 per cent reduction in the recommended annual PM2.5 exposure to only five micrograms per metre cubed.

The MIT study states that the updated guidelines highlight the need to reduce human-released greenhouse gas emissions, but reports that PM2.5 contributions from natural resources would still exceed WHO air quality guidelines, largely due to fires, dust, lightning, and volcanoes.

The researchers’ data revealed that even if we suddenly stopped releasing all anthropogenic emissions, over half of the global population would still be exposed to hazardous levels of PM2.5 compared to the current 90 per cent.

“If you live in parts of India or northern Africa that are exposed to large amounts of fine dust, it can be challenging to reduce PM2.5 exposures below the new guideline,” Sidhant Pai, co-lead author, stated in the study’s press release.

Crowds in a popular street in Cairo, Egypt during the late afternoon. (Izzet Keribar/ Stone/ Getty Images)

The data found that PM2.5 in the Amazon largely came from deforestation fires, whereas emissions in northern Europe were linked to vehicle and fertilizer usage. Different chemicals, such as carbon and nitrogen, were detected in the pollutants, which the scientists say indicates different toxicity properties that may result in a range of negative health impacts.

The study recommends that mitigation and adaptation strategies should be specific for each region as opposed to a global one-size-fits-all approach.

“I hope that as we learn more about the health impacts of these different particles, our work and that of the broader atmospheric chemistry community can help inform strategies to reduce the pollutants that are most harmful to human health,” said Colette Heald, senior author of the study.

In addition to reducing fossil fuel usage, the study recommends routine global measurements of PM2.5 and using that data to implement a number of strategies to improve air quality in various regions.

Thumbnail image: At an intersection in Denver, Colorado, exhaust pours out of a tailpipes from accelerating vehicles onto Santa Fe Drive. (milehightraveler/ E+/ Getty Images)