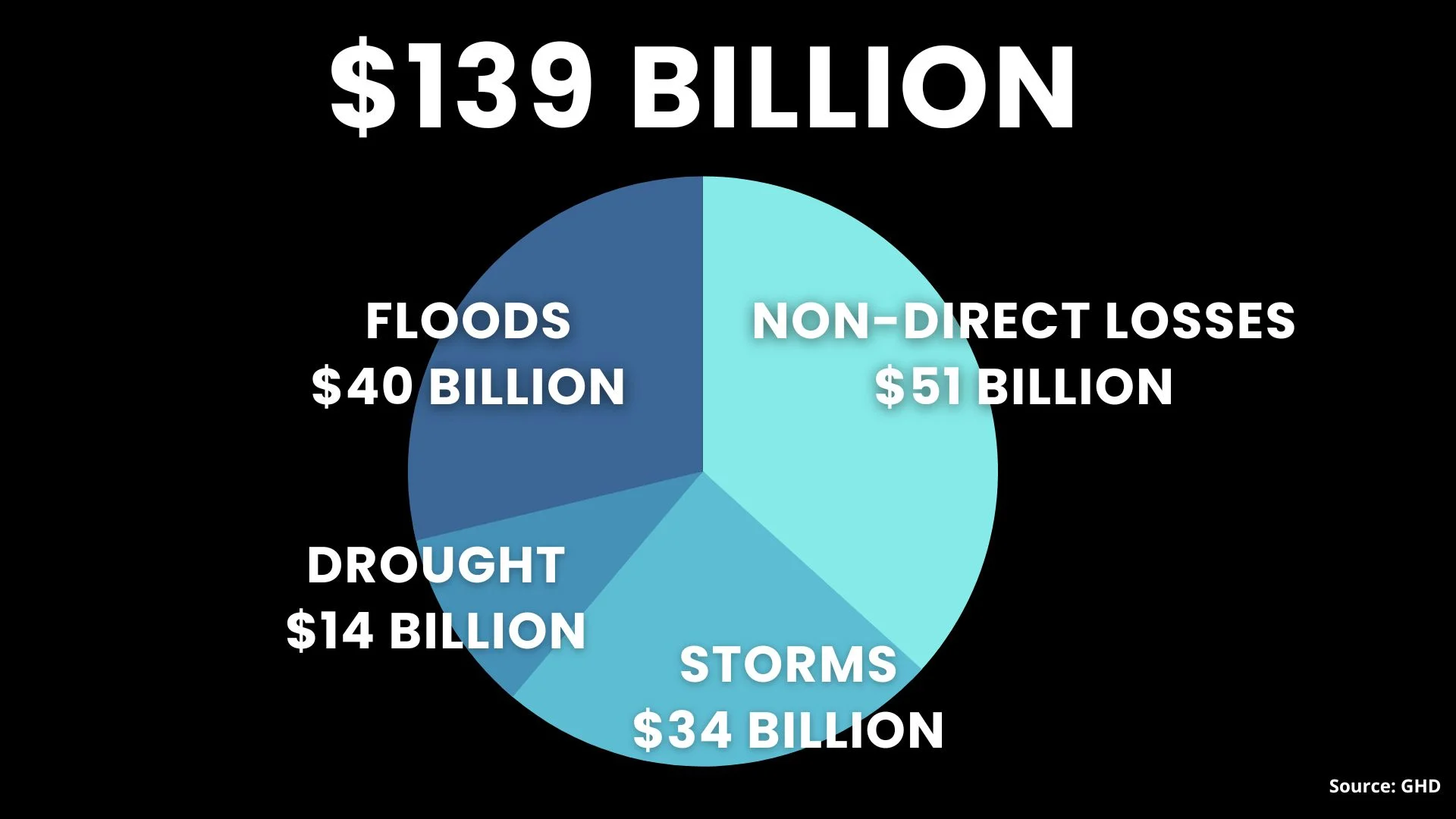

This climate risk could cost Canada's economy $139B

First-of-its-kind research claims our country’s water risk from floods, storms, and droughts could cause major GDP loss over the next three decades.

Oftentimes the main reason for not taking action on climate change comes down to impacts on the economy, but a new report says that will be a big mistake.

Global engineering and architectural professional services company GHD released a report this week — titled Aquanomics: The economics of water risk — that states floods, droughts, and storms could result in a loss of $139 billion to Canada’s gross domestic product (GDP) between 2022 and 2050.

That number rises even higher when looking at the global impact, topping out at $7.2 trillion when adding Canada to the six other countries studied: Australia, China, Philippines, United Arab Emirates (U.A.E.), United Kingdom and U.S.

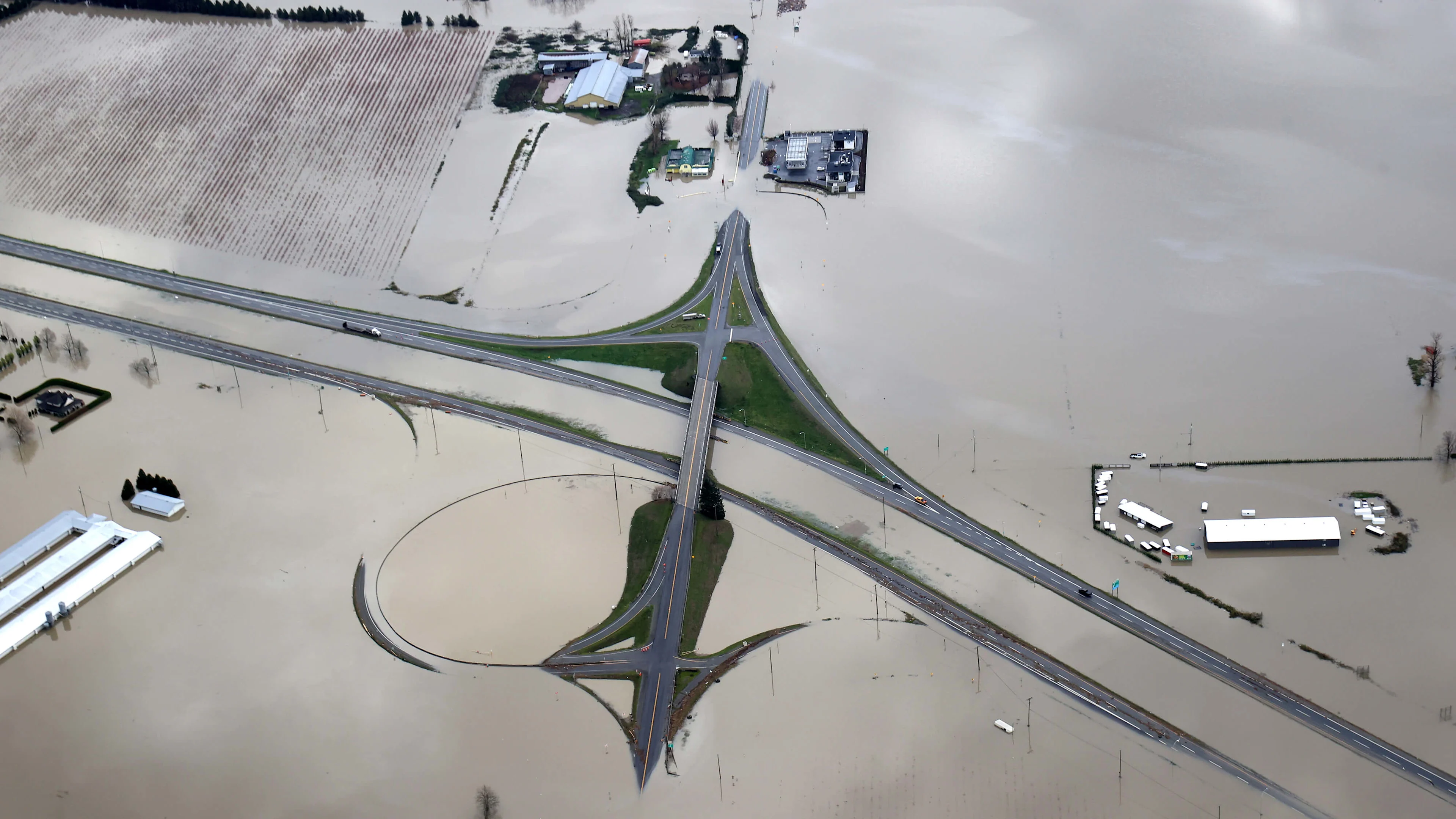

While the study says Canada’s large land mass combined with low population density means less water risk, it still exists. It’s something that most likely remains on the minds of British Columbians, who experienced extreme flooding, fatal landslides, and infrastructure damage when heavy rainfall hit their province for months in 2021.

“I think after last year's floods, a lot of us ask ourselves, ‘What's the true cost of this?’” Zuliana Mawani, the business group lead for water and wastewater for GHD Ontario, told The Weather Network.

Flooding alone could cost Canada $40 billion, according to new research. The report’s direct loss totals were calculated using information from the insurance industry, but it also took into consideration what the cascading costs of that damage could mean. (GHD)

Agriculture, banking and insurance, energy and utilities, fast-moving consumer goods (FMCG) and retail, and manufacturing and distribution are expected to be some of the hardest hit sectors — and that doesn’t even address the human cost.

“What happened in B.C. last year, it essentially cut off major transportation routes, and one of two of Canada's only real international ports. So you can imagine from just a flow of goods standpoint, it was just completely stopped. And so if we start to then break down what the knock on impacts of that,” said Mawani.

Crews assess a large landslide across Highway 7 at Ruby Creek, B.C., in November 2021. The slide was one of several that paralyzed the transportation industry moving goods between the Lower Mainland and the Interior. (B.C. Ministry of Transportation and Infrastructure)

“If you're a manufacturing company that's looking for goods, and waiting for something to come from overseas, the chain just starts to sort of cascade from there.”

The Government of Canada just released a new report called Adapting to Rising Flood Risk. It states damage costs of Canada’s most common and costly natural disaster are expected to rise even higher. The report questions how the government can help attract affordable flood insurance to currently uninsured homes in high risk areas.

The Insurance Bureau of Canada told CBC in 2021 that up to 10 per cent of Canadian homes “are currently uninsurable due to flooding and that estimate could go up as more insurance companies update their risk assessments to account for the rising threat of climate change.”

In an aerial view, floodwaters cover a section of Highway 1 on Nov. 20, 2021, in Abbotsford, B.C. The Canadian province of British Columbia declared a state of emergency following record rainfall earlier that week that resulted in widespread flooding of farms, landslides, and the evacuation of residents. (Justin Sullivan/ Getty Images)

Natural disasters almost always affect insurance rates, as seen in Alberta after the 2013 flood.

It’s also happening to some extent south of the border.

Take Florida, for example, where insurers are cancelling policies, leaving the state, or liquidating at a rapid pace. It’s presented a risky market to home insurance companies for quite some time because of widespread weather-related damage, among other factors like home insurance fraud.

Planning for natural disasters and infrastructure design has been traditionally based on historical data.

“Now we're seeing that we're just wiping that right out and so what we're having to do is clearly take a clean slate and put really more predictive modeling together to figure out what we can expect in the future,” said Mawani.

A growing number of municipalities have declared climate emergencies and are implementing policies to boost resiliency.

Watch below: Extreme weather is changing Canadians' views on the climate crisis

“We did some work with the City of Vancouver, and Calgary as well, to redefine what the intensity duration and frequency curves were for their rainfall and … what we found is that the precipitation in totality will remain the same but it's going to be in the short, very intense storms. And from a design of infrastructure perspective that's game changing, right? How we want to be sure that our infrastructure is resilient and able to accommodate those intense storms.”

So how can Canada prepare?

“We know it's not an if but a when,” said Mawani. “And so we talked about an adaptation, optimization and prioritization, and it's just looking at making sure that these are considerations that are made when we're building new infrastructure.”

Thumbnail image: A home and car sit submerged in floodwaters on Nov. 21, 2021, in Abbotsford, B.C. (Justin Sullivan/ Getty Images)