Dealing with climate anxiety? Here’s some ways to help

Find out how to look past the doom and gloom of the climate crisis towards hope.

In the news there have been some terrifying headlines the past few years.

Phrases like “code red for humanity” and a million species at risk of extinction have flashed across the internet, causing alarm for many.

It’s led some to experience what many are now calling eco or climate anxiety.

“I think climate anxiety has sort of emerged as this catch-all term. It's sort of like all these emotions that people feel when they're confronted with climate change,” Grist climate change journalist Kate Yoder told The Weather Network (TWN).

“So that could be worry, fear, anger, grief, despair, you know, this whole host of emotions. And a lot of people, like experts, have stressed that this is like a completely rational, reasonable response.”

During her time reporting on climate change, Yoder says she’s noticed a rise in how often climate anxiety is being discussed.

“I've actually been tracking Google searches. And over the … past two years, there's been this massive increase ... there was like a six-fold increase in people just googling climate anxiety,” she said.

“And then I just checked again, and there was like a massive spike last month. And I think that's really interesting because that shows that people are really wanting to find these resources, and like really grappling with this issue.”

Talking helps

Neal Haddway knows just how heavy it’s weighing on some.

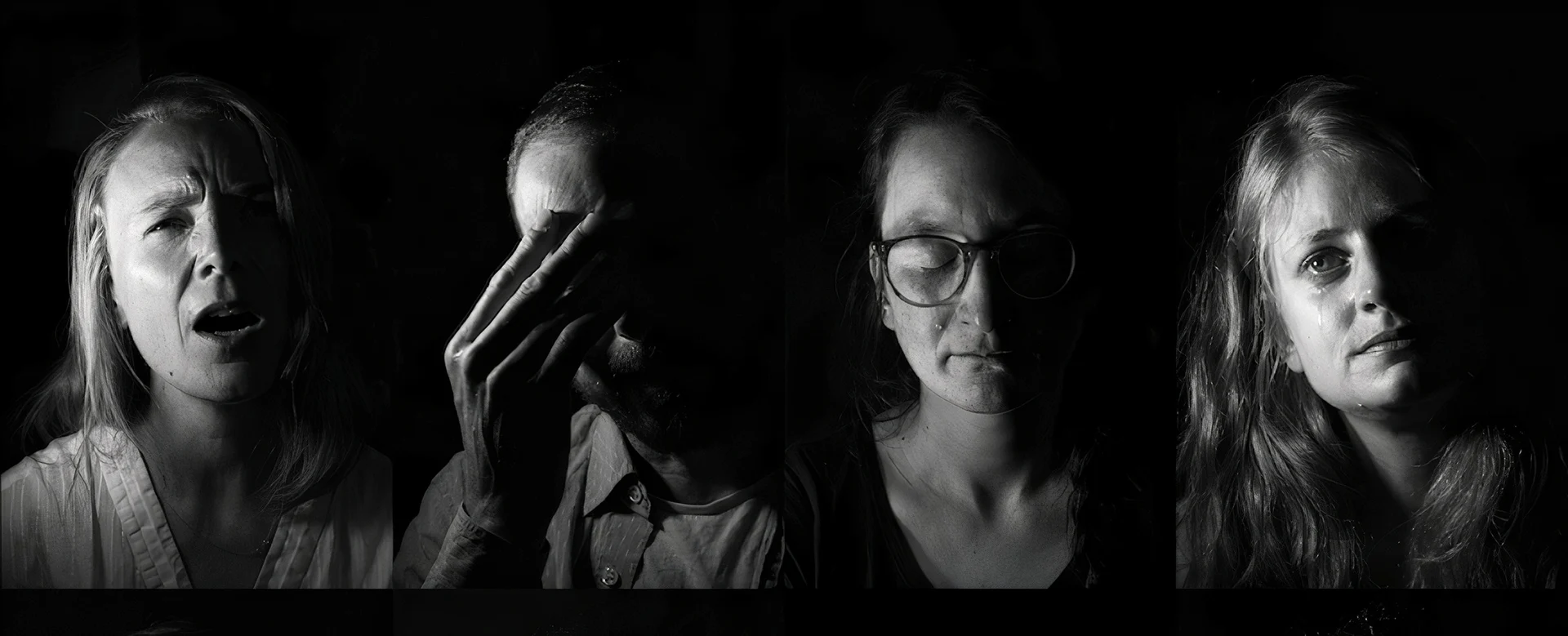

The photographer living across the pond in London started interviewing people working with the environment for a new online exhibit called Hope? and how to grieve for the planet.

“I started this project last summer after an extensive discussion with a close friend in Berlin about how hopeless we felt about the future,” Haddaway told TWN. “I wanted to know if other people working with the environment felt the same, and if we could learn from one another. “

He says the project turned into a hybrid of documentary photography and portraiture, as the images are from real conversations and not posed.

“My participants helped to select the images to make sure the emotions displayed represent how they felt. It’s all very raw and real,” said Haddaway.

“Some words were more common than others — frustration, guilt, sadness. I wasn’t really prepared for the tears, and I cried a lot.”

Photographer Neal Haddaway says he wanted those participating to feel more connected and less alone about the massive challenges facing our world. (Neal Haddaway)

But there was a cathartic release as well, and hope.

Britt Wray, author of the recently released book Generation Dread, says that sentiment is extremely important when it comes to one's mental health.

“It's totally healthy to feel concerned about what's happening because there is a real existential threat at play with environmental degradation and the climate crisis,” Wray told TWN, adding there’s nothing wrong with those thoughts as a crucial first step.

“Many of us have not been taught how to feel and embrace challenging feelings that are kind of unavoidable and really difficult scenarios.”

The next really important thing is to be able to come together with others who can contain the feelings, she says.

“There's a burgeoning space of climate aware therapists, for example — people who are professional mental health workers who are validating these worries and helping people move through them with more support,” said Wray. “There are community groups and peer networks to have these kinds of emotionally grounded conversations.”

Join a group

Pointing to groups such as Good Grief Network’s 10-step program modelled after Alcoholics Anonymous and Climate Awakening’s virtual sessions, Wray says there are a variety of free resources online.

“There's All We Can Save circles, there's Climate Cafés. I mean there's like a cottage industry of peer support for people to have that containing setting because it's hard to have these conversations at the dinner table, with your colleagues, you know, just out in the world as we are in a process of all collectively waking up to how much danger we're in with the climate crisis,” Wray continued.

“What's going to happen when we have never before seen climate migrations happening in the proportions of the hundreds of millions, and what that will mean for conflict and violence being stoked over dwindling resources and competition.”

All these things invoke a lot of anxiety about what that world really looks like.

Wray says instead of clinging to uncertainty as this anxiety-inducing stressor, we can learn how to harness anxiety as a resource to cope with the climate crisis because there are a variety of possibilities ahead of us.

“They're not all set in stone,” she said, adding it’s also important to work with one's nervous system in order to fit back into a window of tolerance for difficulty.

The window of tolerance concept coined by a psychiatrist Dan Siegel says we all have this zone in which we are optimally operating, where we have our best access to our finest cognitive capacities. We aren't so stressed out and hyper vigilant that we get pushed out of that window. And we're not so numb with depression that we're kind of detached out of the window.

“A bunch of really stressed out humans on a warming planet with dwindling resources does not bode well for how we're going to treat each other if we are not within that window of tolerance and able to be caring, compassionate people,” said Wray.

“If we don't have access to it, we are more in a rigid, reactive kind of animal mode — fight, flight freeze becomes how we operate.”

One thing that doesn’t help is what Wray calls “irresponsible storytelling.”

“We're not doing the work of telling the stories of how to intervene, of showing real examples of ways that people are changing their lives to address this,” she said.

Britt Wray, a human and planetary health fellow at Stanford University, literally wrote the book on how to tackle climate anxiety after years of research. (Submitted by Britt Wray)

What you pay attention to grows, and Wray says people need to be aware of mindful consumption — which could mean deleting social media apps if it becomes too much.

Wrays says the best things to ground us in the moment and comfort our nervous systems in times of emotional drama include practices like yoga, mindfulness, meditation, and spending time intentionally in nature for its therapeutic benefit.

The goal: recharging your battery instead of giving up — which Wray says can be a dangerous self-fulfilling prophecy.

“It can feel more relaxing to land on an apocalyptic narrative and commit to it, even though it's spelled out something truly terrifying, because then at least your mind doesn't have to hold two opposing thoughts simultaneously and like deal with the cognitive dissonance, as it were, around this crisis,” she said.

Yoder agrees.

“I think that that belief that it's too late, I think that's partly a communication failure on the part of the media and scientists and others who, I think with really good intentions, highlight the worst because they think that it will motivate people to take action. And sometimes that can work. And I think it's already sparked a lot of change.”

But at the same time those fear-based messages can backfire if people feel like they can’t take meaningful action.

Better supports needed

During her time reporting on the issue, Yoder says studies have shown our health-care systems are not currently up to the task.

“Climate anxiety in particular is often seen as this personal problem with an individual solution. Like, you just need to take action, like go to a protest, or, you know, change your lifestyle,” she said. “I think that that can be helpful. And we do need that cultural change, but that action ultimately needs to come from people in power.”

Governments can not only help tackle the climate crisis by building better infrastructure, but providing additional mental health support and funding for first-responders and communities dealing with extreme weather like flooding, wildfires, and droughts.

“I've seen studies that have a lot of interesting statistics around that. So 20 to 30 per cent of people who live through hurricanes develop depression or PTSD in the months afterward. And I think it's similar numbers for flooding,” said Yoder. “And wildfires, for example, have been linked to increases in substance abuse, sleeping problems. And temperatures above (32 C), when that happens, more people are reporting psychiatric visits.”

But governments need political pressure to do something.

In her time researching her book, Wray says that can come from working in groups.

“People don't sit around waiting to feel hopeful before they act,” she said. “They roll up their sleeves and come together with others in situations that feel hopeless.”

Thumbnail Image: London-based photographer Neal Haddaway spoke to a diverse group of people working in the environmental field for their thoughts on the future of our planet for an online project. (Neal Haddaway)