Fewer dead bugs on your windshield is actually a bad sign for insects

Have you noticed that you don’t have to squeegee your car windows as often anymore? Entomologists certainly have, and they are concerned it points to a serious worldwide decline in insect populations and diversity.

The Weather Network's Kyle Brittain recently shared pictures from an Alberta road trip into Strathmore showing his car entirely covered with bug carcasses after driving through a massive mayfly hatch.

Mayflies emerge from their water larva stage in swarms through the spring and summer. Ask any fishing enthusiast: mayflies are such an important source of food for fish that they inspired fishing flies.

But the sight of Kyle’s filthy car is becoming the exception, due to the global decline in insect populations.

People over the age of 30 may remember bug-encrusted windshields as a normal part of summer road trips in their childhood. Over the past few decades, it seems we’ve had to wash our windshields a lot less often.

This has been dubbed by entomologists and conservation scientists as the windshield phenomenon.

Maxim Larrivée, director of the Montreal Insectarium, explained it this way: “The windshield phenomenon is a really simple example that every Canadian has witnessed over the past 30 years. When you go on a road trip, your windshield is much cleaner than it used to, and the obvious reason is that there are a lot less insects.”

It is a powerfully simple illustration that can spark reflection and help us grasp the amplitude of the decline in insect population and diversity. But the windshield phenomenon — and the insect decline more generally — have been validated by a number of studies.

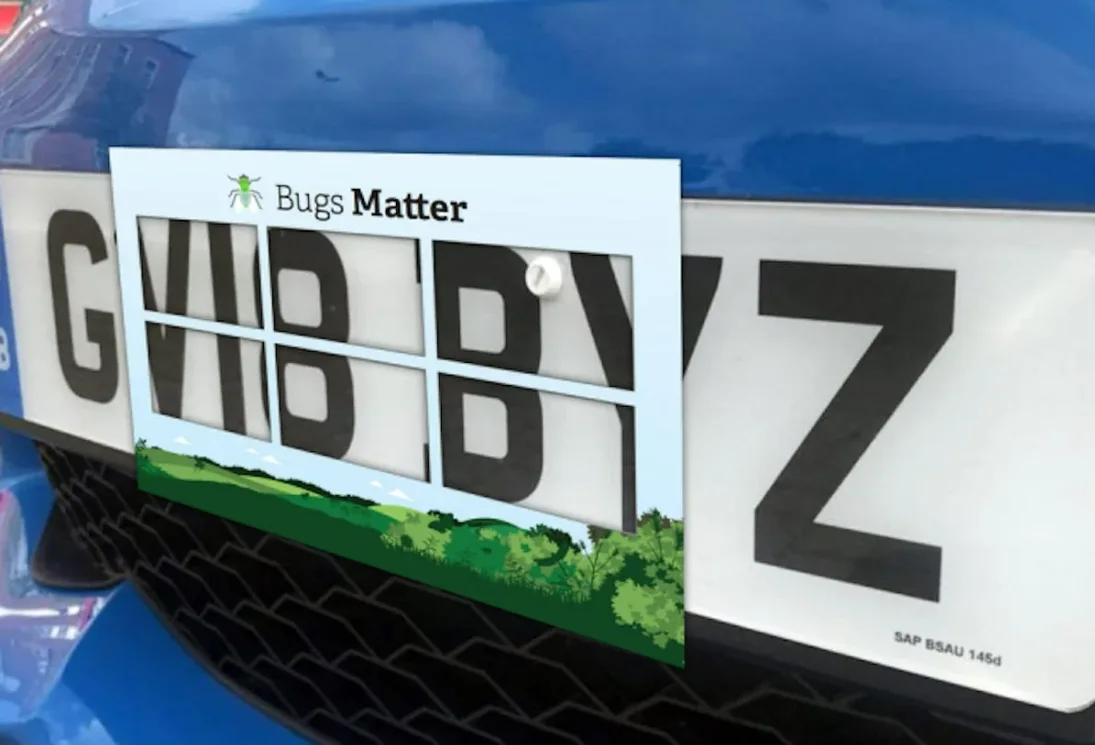

In the U.K., the Kent Wildlife Trust and Buglife are running a citizen science project to tackle the question directly.

In 2021, they conducted an experiment where volunteers attached a grid on their licence plate to document the number of insects squashed on their journey. This method had been employed for a similar survey in 2004, so the researchers were able to compare the results over time.

Their conclusions were concerning, showing a 71.5 per cent decline in the number of insects sampled on cars in Kent between 2004 and 2021. Convinced of the need for further research and monitoring, they are repeating the experiment this year.

A grid stuck on a car licence plate to count hit insects for the Bugs Matter project. (Kent Wildlife Trust)

Other studies have found similarly alarming declines elsewhere. In Western Europe, the Krefeld Entomological Society documented a 75 per cent decline in insect biomass in protected areas — leading to a flurry of headlines about an “insect armageddon” in 2017.

Some species of insects are declining faster — more complex beetles, flying insects, and species that depend on wild prairies, which have been widely replaced with wheat and corn fields.

Fewer insects might not seem so bad to mosquito-haters, but their loss has a knockdown effect on other species. In a now famous study conducted by Chris Grooms at Queen's University in Kingston, Ont., biologists dug through 48 years of excrement deposited by chimney swifts — a fairly common bird that feeds exclusively on flying insects.

From the very bottom of the pile of sediment, they found that the birds’ diet used to be composed mainly of beetles, but as they got closer to the top, and more recenly deposited, they found more chemicals associated with DDT and the remains of smaller, less calorie-rich insects. This change in diet had a definite negative impact on the swift population, and the parallel decline of flying insects and aerial insectivores has been more widely documented since.

Insect particles (magnified eight times) recovered from the chimney swift guano deposit in Kingston, Ont. (Chris Groom/ Queen's University)

And the consequences of insect decline are not just felt by the wildlife. As Larrivée put it: “Consequences are pretty dire, but for most people, the consequence is in their pocket.”

Insects play an important economic role as pollinators of our fruits and veggies — their loss means that produce will become more scarce and expensive.

Insects also keep each other in check. One species disappearing can open the way to a more damaging one. The mountain pine beetle, for example, has been blamed for the wildfires that raged through the western United States and Canada in 2020. Although the causes of wildfires are multiple and overlapping, bark beetles (which are attracted to drought-stressed trees) leave a lot of dead timber, or as Larrivée put it, “a forest of matchsticks.”

Trails left behind by the mountain pine beetle scar a fallen lodgepole pine log in Beaverhead-Deerlodge National Forest on Sept. 12, 2019. The insects have killed more than six million acres of forest across Montana since 2000. (Chip Somodevilla/ Getty Images)

The causes of insect decline are many, truly death by a thousand cuts. Larrivée named habitat destruction and conversion to agricultural production, pesticide use of course, and globalization leading to the introduction of destructive or invasive species. Climate change also plays a role, exacerbating and amplifying these other pressures. Extreme weather events, more frequent due to climate change, have the potential to push a threatened insect species over the brink.

A pollinator garden filled with life, designed specifically to attract insects with native flower species. (Valerie Bourdeau)

The famed entomologist E.O. Wilson called invertebrates “the little things that run the world” and their loss should be of deep concern for all who share that world. Thankfully, insects’ rapid generation time means they can bounce back, if we give them the chance.

Creating healthy habitats for insects to feed, reproduce and hibernate is key. That can mean planting a pollinator garden (or even flower boxes) with native plant species, leaving yard waste alone in the fall and resisting the urge to mow in the spring. You can also contribute to the ongoing study of insect populations through citizen science initiatives like Mission Monarch or eButterfly.

One final suggestion from Maxim Larrivée: “Talk about it. With your loved ones, or your elected officials. Make them understand that insect diversity is important for your well-being.”

Thumbnail image: Dead insect on the windshield of a car. (diatrezor/ iStock/ Getty Images Plus)