Disastrous megaflood could cause historic damage in California, study warns

The simulated megaflood would put parts of Los Angeles and other cities underwater and cause $1 trillion in damage, which exceeds the cost of all other natural disasters in global history.

California, the state that is the top producer of agricultural products in America, is in the throes of historic drought conditions and continues to invest billions into water infrastructure to keep the taps running and croplands hydrated.

While the lack of water remains one of the most pressing issues for the state, researchers from UCLA and the National Center for Atmospheric Research warn a different type of water crisis threatens California.

Their study, published in Science Advances, warns that a megaflood of such extreme proportions could become the most expensive natural disaster in history, and it could happen this century.

Climate models, historical records, and sediment deposits from thousands of years ago show that the state typically sees extreme flood events every 100 to 200 years that overwhelm major valleys and travel hundreds of kilometres.

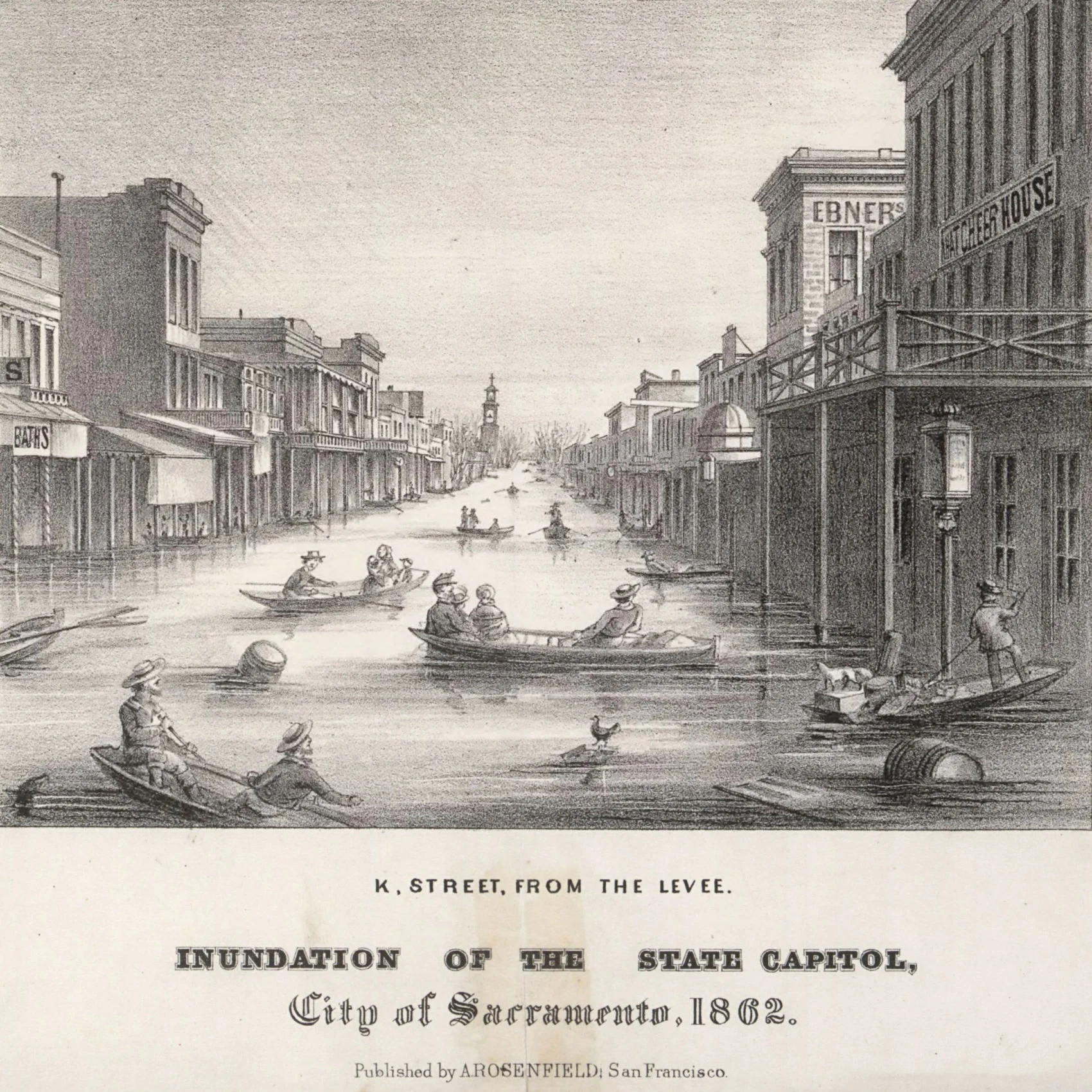

Nearly 200 years ago an atmospheric river event, dubbed the Great Flood of 1861-1862, resulted in consecutive weeks of winter storms that brought historic amounts of rain and snow. The study stated that the interior Sacramento and San Joaquin valleys were “turned into a temporary but vast inland sea nearly [482 kilometres] in length,” which covers what is now Los Angeles and Orange counties.

Downtown Sacramento during the Great Flood of 1862. One-third of the state’s taxable land was destroyed and Governor Leland Stanford was forced to row to his inauguration. (A. Rosenfeld/Wikimedia Commons)

NOAA defines atmospheric rivers as “long, narrow regions in the atmosphere — like rivers in the sky — that transport most of the water vapour outside of the tropics” and states that the amount of water vapour is roughly equivalent to the average flow of water at the mouth of the Mississippi River.

“Atmospheric rivers play a tremendous role in modulating the water availability in any given watershed. Many of these atmospheric rivers are beneficial, but there's a fine line between beneficial and destructive,” said Tyler Hamilton, a meteorologist at The Weather Network.

“Robust atmospheric rivers in quick succession can be problematic. Increased snowmelt runoff and soil saturation amplify the threat of slope failure and infrastructure damage.”

RELATED: Climate change threatens Coachella Valley, Palm Springs tourism, study says

The researchers stated that a growing body of evidence is indicating that climate change is increasing the risk and intensity of extreme precipitation events, including atmospheric rivers, along the Pacific coast of North America since a warmer atmosphere holds higher levels of water vapour that can fall as precipitation.

Rising global temperatures are also influencing other atmospheric patterns, such as El Niño, which affects winter rainfall and snowfall in this part of the world.

WATCH: Human remains revealed as Lake Mead hits historic low amid drought

Given the recurring nature of significant flooding events every 100 to 200 years in California, the researchers modelled what this phenomenon would look like during the projected climate in 2081-2100. The scenario simulated multi-week winter storms that were similar in nature to those that occurred during the Great Flood of 1861-1862 and El Niño conditions.

In the future scenario, the data showed that runoff in the Sierra Nevada Mountains could increase by up to 400 per cent with more intense hourly rainfall rates and stronger winds. Certain parts of California would see around 2,500 mm of rain per month and over six metres of snow on the mountain peaks. The increased runoff from this precipitation would lead to devastating landslides and significant volumes of debris, which could be particularly hazardous in areas that have been damaged by wildfires.

Flooding damaged the Oroville Dam main spillway after record 2017 storms in parts of Northern California. The simulated storm events would bring much more precipitation over a wider region. (William Croyle/California Department of Water Resources)

“Every major population center in California would get hit at once — probably parts of Nevada and other adjacent states, too,” Daniel Swain, UCLA climate scientist and co-author of the paper, stated in a press release.

In 1862 the entire state’s population was 500,000 but has now grown to 40 million. The researchers estimate that a flooding event of a similar magnitude would put parts of certain cities, including Los Angeles, underwater and cause $1 trillion in damage, which exceeds the cost of all other natural disasters in global history.

“Our initial atmospheric modelling results presented here demonstrate that extremely severe winter storm sequences once thought to be exceptionally rare events are likely to become much more common under essentially all plausible future climate trajectories — suggesting that 20th-century hazard mapping, emergency response plans, and even physical infrastructure design standards may already be out of date in a warmer 21st-century climate,” the study concluded.

The researchers stated that some solutions to increased flood risks are floodplain restoration, levee setbacks, forecast-informed reservoir operations, and revised emergency evacuation plans that consider transportation disruptions that have never been witnessed before.

Thumbnail image: Heavy rain in the Californian region. (middelveld/ E+/ Getty Images)