East Antarctica’s Conger Ice Shelf disintegrates. What are the experts saying?

Global warming is making events like this more likely.

The Conger Ice Shelf in East Antarctica, thought to be stable and relatively unaffected by climate change, completely disintegrated in mid-March. Here's what the experts are saying about this event.

Just a few weeks after scientists logged the smallest sea ice extent for Antarctica in over 40 years, temperatures soared across the eastern part of the continent to roughly 30°C higher than normal. In the aftermath, satellite imagery captured something completely unexpected. The Conger Ice Shelf — a roughly 1,200 square kilometre sheet of glacial ice along the coast of East Antarctica — had shattered in just a matter of days.

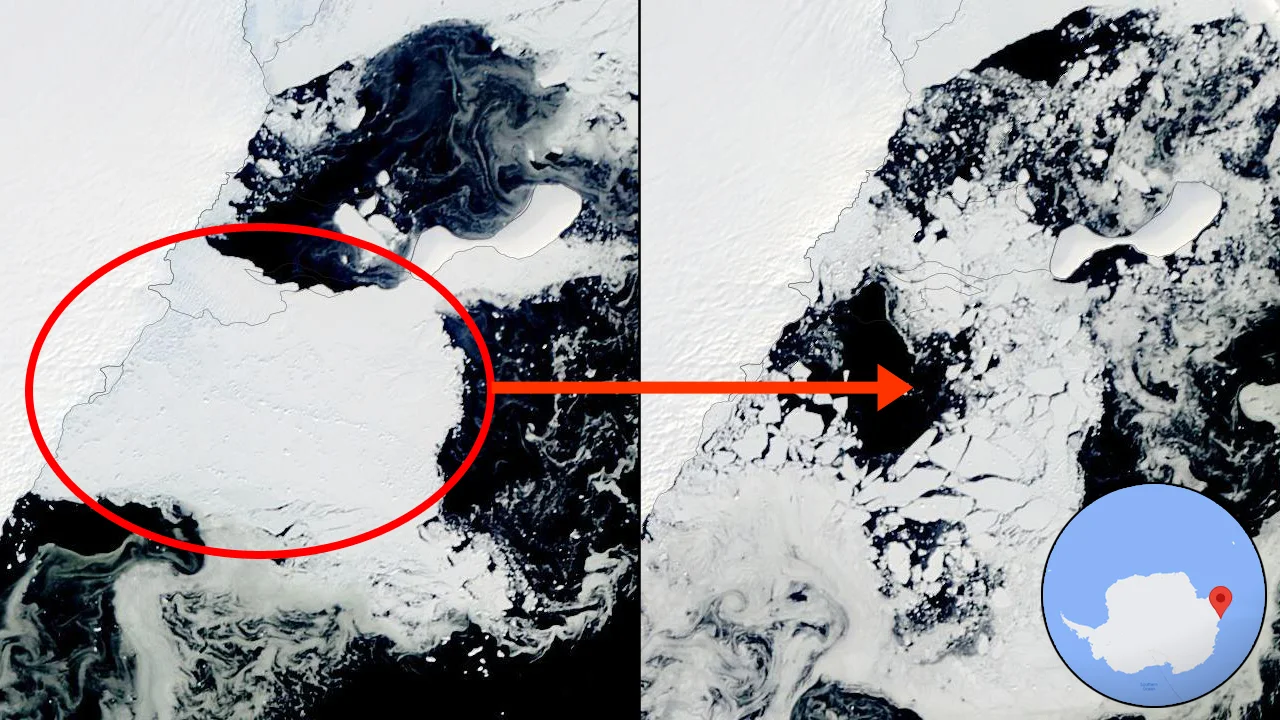

Satellite images show the Conger Ice Shelf relatively intact on March 12 (left), but a similar overpass on March 21 shows the ice shelf completely gone. North is to the right side of the image frames, west is towards the top. The inset map shows the location of the former Conger Ice Shelf along the coast of Antarctica. Credit: NASA/Terra MODIS/Scott Sutherland

Since the late 1970s, Conger has been on a slow decline. Pinned between the shores of the Wilkes Land region of East Antarctica and Bowman Island, this ice shelf was once connected to the larger Shackleton Ice Shelf to the west. That connection broke down over 20 years ago, though.

Since then, the western edge has retreated further until, in 2020, the ice shelf covered an area of just over 1,600 square kilometres — close to three times the size of the city of Toronto. Over the past two years, another 400 square kilometres of ice was lost.

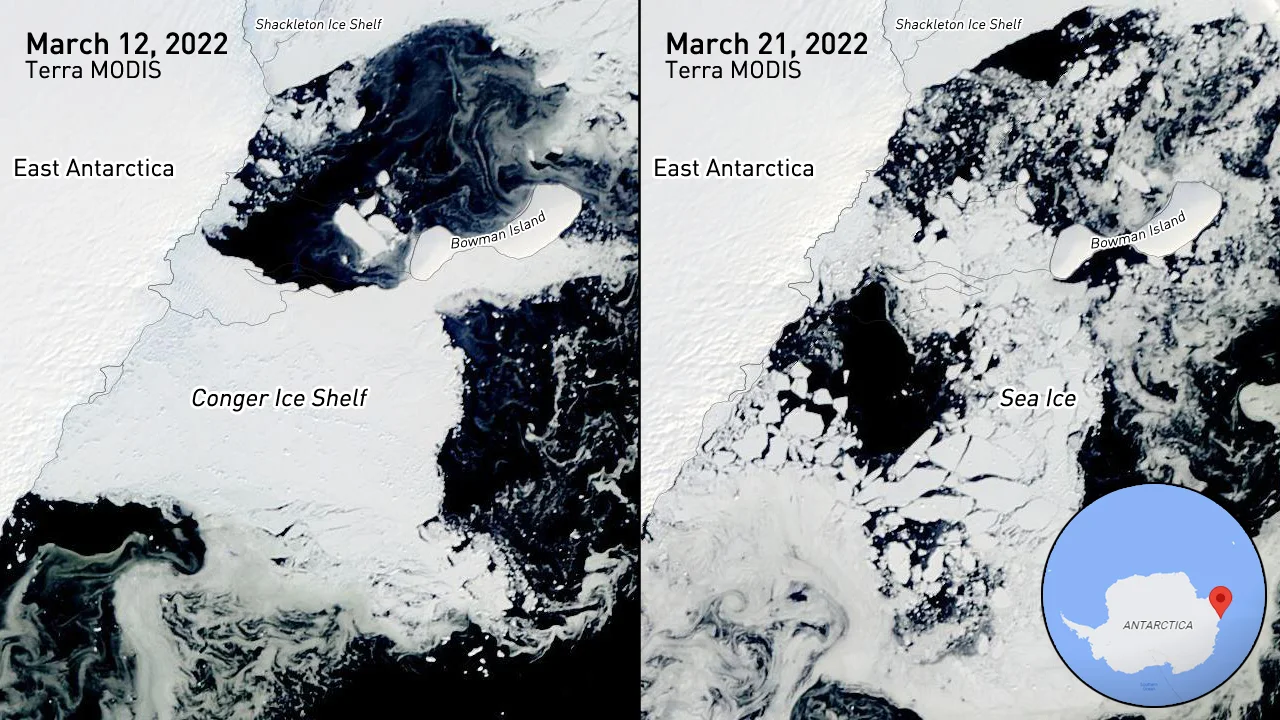

Then, on March 17, the US National Ice Center reported a new iceberg named C-38, measured at around 550 square kilometres, in the waters near Bowman Island. In that same press release, they said that the Conger Ice Shelf was gone.

"C-38 comprised virtually all that remained of the Conger ice shelf," they wrote.

The entire 1,200 sq km ice shelf had collapsed, leaving behind C-38 and a scattered collection of sea ice.

Newly-calved iceberg C-38 is visible in this satellite image from Sentinel-1A on March 17, 2022. Also visible is iceberg C-37, which is the last remaining piece of the former Glenzer Ice Shelf, which was located just to the west of the Conger Ice Shelf. C-37 broke away from its attachment to Bowman Island on March 7, 2022. Credit: USNIC

Iceberg calving is nothing new to Antarctica.

"The breaking and detachment of parts of ice shelves is a natural process," glaciologists Hilmar Gudmundsson, Adrian Jenkins, and Bertie Miles wrote in a piece penned for The Conversation. "Ice shelves generally go through cycles of slow growth punctuated by isolated calving events."

"But in recent decades, scientists have seen several large ice shelves undergoing total disintegration," they explained.

According to Gudmundsson, Jenkins, and Miles, the exact cause of the Conger Ice Shelf collapse is unclear. While the collapse occurred at roughly the same time as the 'heat wave' that impacted East Antarctica, it appeared to begin before those weather patterns developed. Thus, the timing may only be a coincidence.

ANTARCTICA'S SAFETY BAND

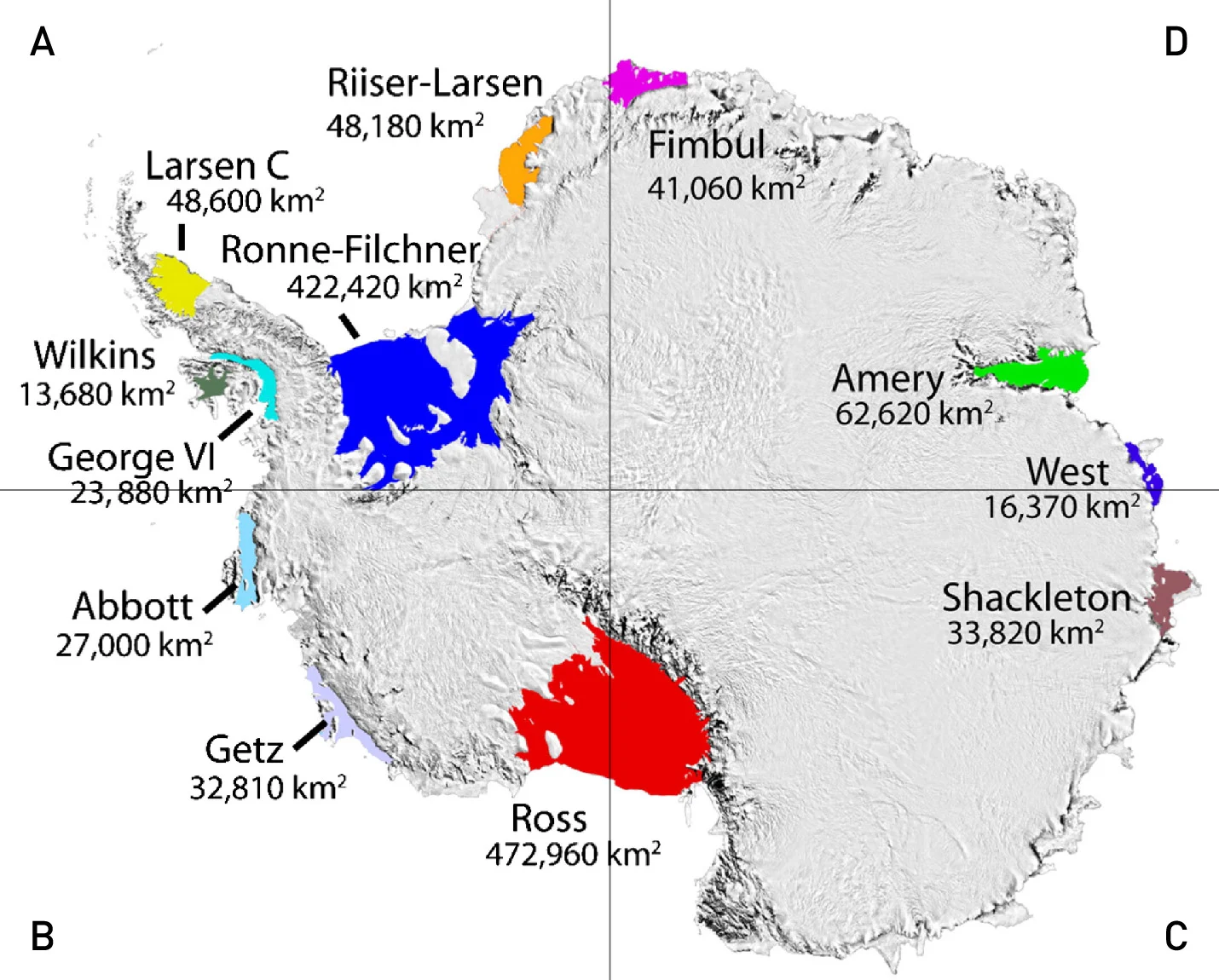

Antarctica has dozens of ice shelves along its coastlines.

They form when glacial ice, under the force of gravity, flows down to the coastline and then pushes out over the water. While it is rooted to the continental shoreline, the buoyancy of the ice causes it to float, forming a shelf over the water. Once the ice shelf forms, its buoyancy pushes back against the glacier, holding back the advance of the upstream ice. For this reason, researchers sometimes refer to ice shelves as the "safety band" of Antarctica.

However, as ocean currents, warm waters, and strong winds stress the leading edge of the ice shelf, icebergs break off and float away. Losing ice from the end of the ice shelf weakens the pushback of buoyancy, allowing the glacier to advance.

Watch below: Ice shelves are the support system for Antarctic glaciers.

The loss of an entire ice shelf speeds up this process considerably, and in some cases, it can lead to a rapid advance or even a significant collapse of the glacier. Floating ice shelves have already been contributing to global sea levels for much longer than we have been measuring it. However, if those ice shelves disappear, it allows more ice to flow over the water from on land, and that new ice pushing out over the water causes global sea levels to rise.

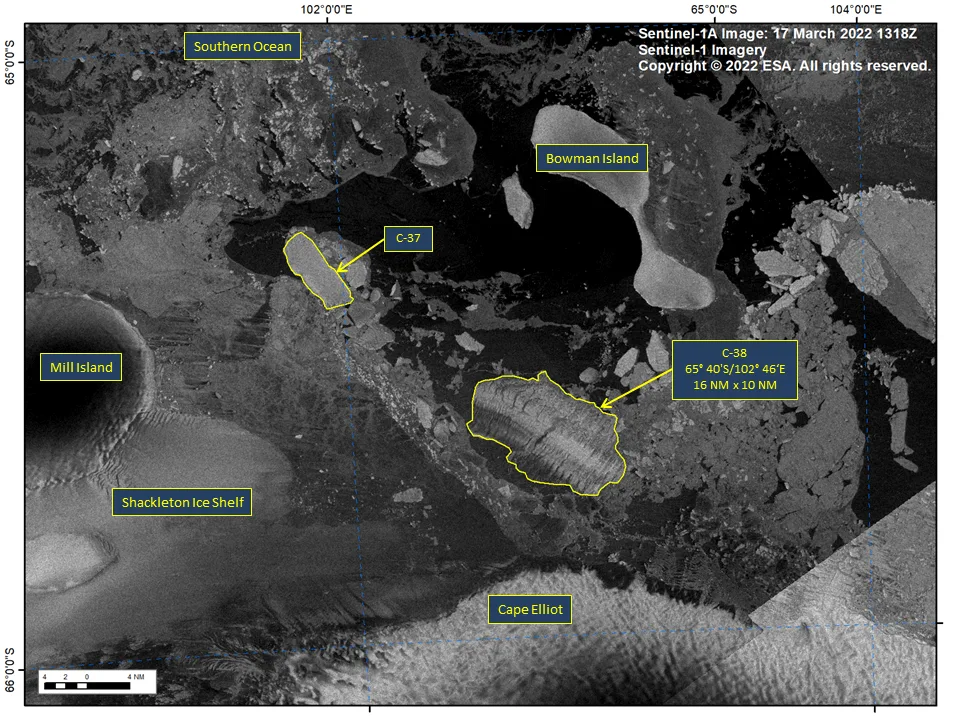

The Larsen ice shelves are perhaps the most infamous so far. Located near the northern tip of the Antarctic peninsula, Larsen A collapsed in 1995, while Larsen B disintegrated in 2002. In early February of 2022, a large mass of multi-year sea ice had accumulated and frozen itself to the shoreline of the Larsen B embayment. This 'landfast ice' was seen to slow the advancement of the glaciers around the embayment somewhat, but then that ice completely broke apart in a matter of days.

Larsen C, located farther south along the peninsula, calved off iceberg A-68, which held the title as largest iceberg in the world from 2017 to 2021. The rest of Larsen C continues to hold fast. Still, scientists are watching it closely as Larsen A and B collapses were preceded by large icebergs breaking away.

This view of the Larsen A and B embayments includes annotations showing the past extents of the ice shelves, and includes an inset map of the entire Larsen ice shelf. Credit: NASA Earth Observatory

GLOBAL CONSEQUENCES?

The complete loss of the Conger Ice Shelf is something of a surprise, though. It is also a cause for concern.

In East Antarctica, we have not generally seen the same level of impacts due to climate change that have been witnessed in West Antarctica. Based on that, it was thought that this ice shelf would likely persist for many years to come.

Fortunately, the loss of this particular ice shelf will apparently have few immediate consequences.

It is not expected to contribute to the global rise of ocean levels because the iceberg and sea ice that once made up the ice shelf displaces the same amount of water the ice shelf did before the collapse. The only change has been that the ice is no longer attached to the glacier on land.

Also, while the loss of an ice shelf usually raises concerns about impending sea level rise, according to Gudmundsson, Jenkins, and Miles, the Conger collapse is unlikely to have any long-term significance. Due to the shape of the ice shelf, and because the area where the ice shelf grew from is small, they say it did not appear to be a significant "buttress" to the flow of the glacier.

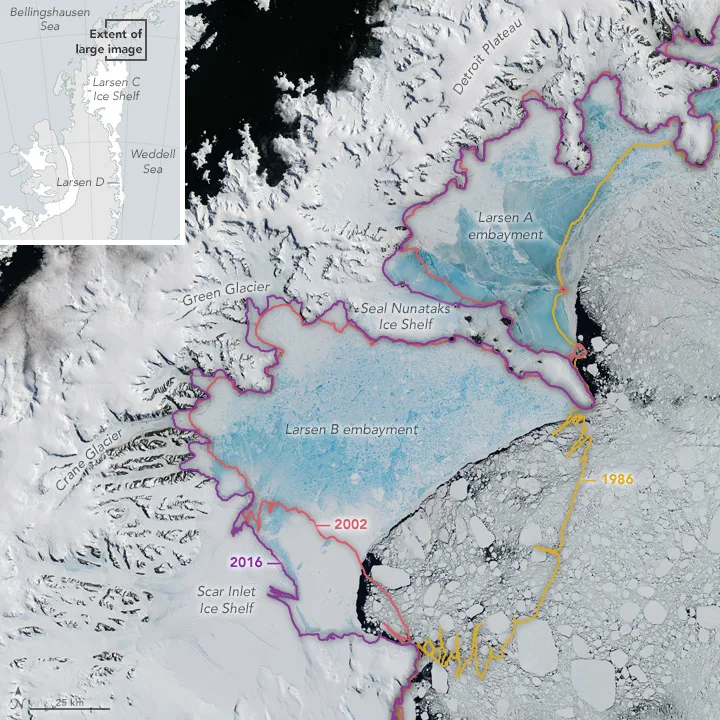

This map of Antarctica divides the continent into the quadrants used to name icebergs. The major ice shelves surrounding the continent are also included. Credit: Ted Scambos/NSIDC/Scott Sutherland

However, they add that global warming makes these events more likely to occur.

"And as more and more ice shelves around Antarctica collapse, ice loss will increase, and with it global sea levels," they wrote. "There is enough ice in the West Antarctic ice sheet to raise sea levels by several meters, and if East Antarctica starts losing significant amounts of ice, the impact on sea levels could be measured in tens of meters."

"Not everything that happens in nature is due to global warming alone," they explained.

"Antarctica loses mass through the discharge of icebergs and waxing and waning ice shelves as part of a natural cycle. But what we are seeing now, with the collapse of the Conger ice shelf and others, is the continuation of a worrying trend whereby Antarctic ice shelves undergo area-wide collapse one after another."