Even in the midst of winter, Antarctic sea ice sets new record low

The loss of ice from West Antarctica should be a warning to the world.

After setting a new record for lowest summer extent earlier this year, Antarctic sea ice saw a new record low going into winter as well.

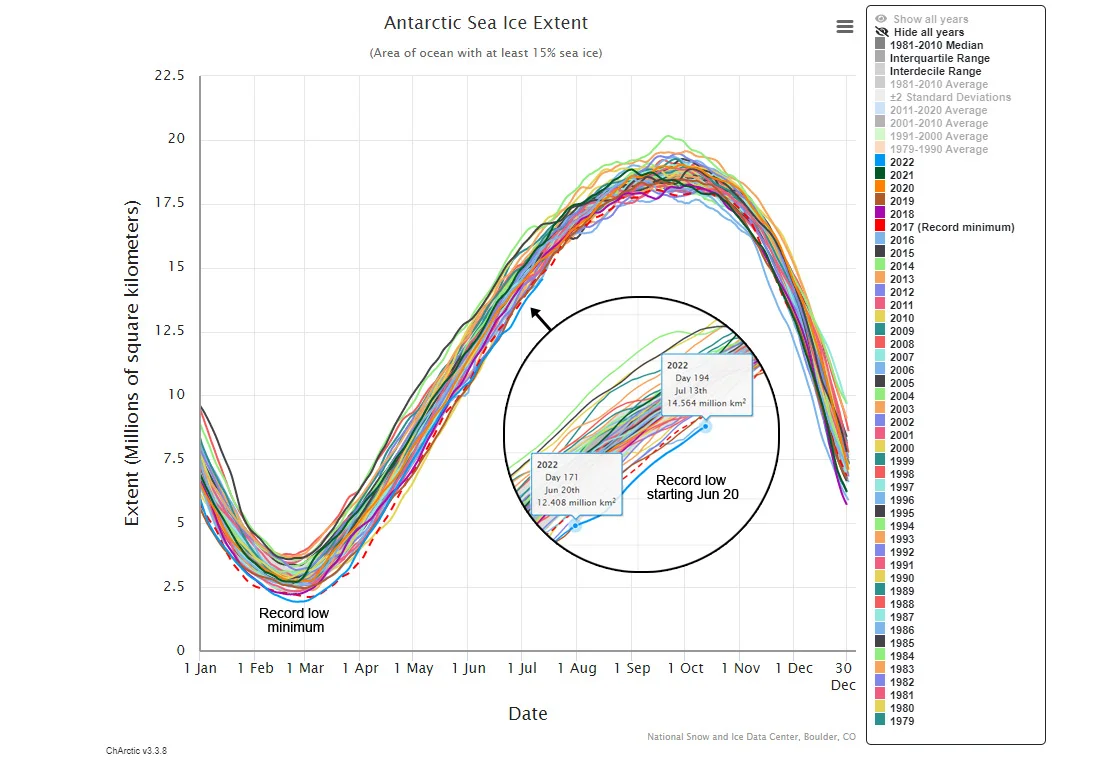

At the southern extreme of our planet, the continent of Antarctica is surrounded by floating ice, either frozen directly from the ocean or due to fresh water flowing off the continent's glaciers and ice sheets. Each year, the extent of that sea ice grows and shrinks with the seasons. It reaches a maximum extent sometime in late September or early October, towards the end of southern winter. It then melts away to a minimum extent towards the end of southern summer, typically in February or March. Between 1979 and 2021, Antarctic winter sea ice has covered as much as 20 million square kilometres (roughly the full extent of the Southern Ocean), while summer sea ice extent has shrunk down to as little as two million sq km.

In 2022, from Feb. 8 to March 8, the minimum fell below two million sq km for the first time in the satellite record. A new record low extent was set on Feb. 25 of just 1.924 million sq km.

The sea ice has been expanding since then, as temperatures drop and that region of the world is plunged into the darkness of winter. However, as of June 20, the day before the start of southern winter, the Antarctic sea ice extent has been setting daily record lows for this time of the year.

This graph shows the seasonal cycle of Antarctic sea ice extent, in millions of square kilometres, from 1979 up to July 13, 2022. The inset view zooms in on the past few weeks, to highlight the extreme low extents recorded since June 20. (NSIDC/Scott Sutherland)

According to the National Snow and Ice Data Center, June sea ice extents have been something of an anomaly, in that they do not match up with the wind patterns being experienced throughout the month.

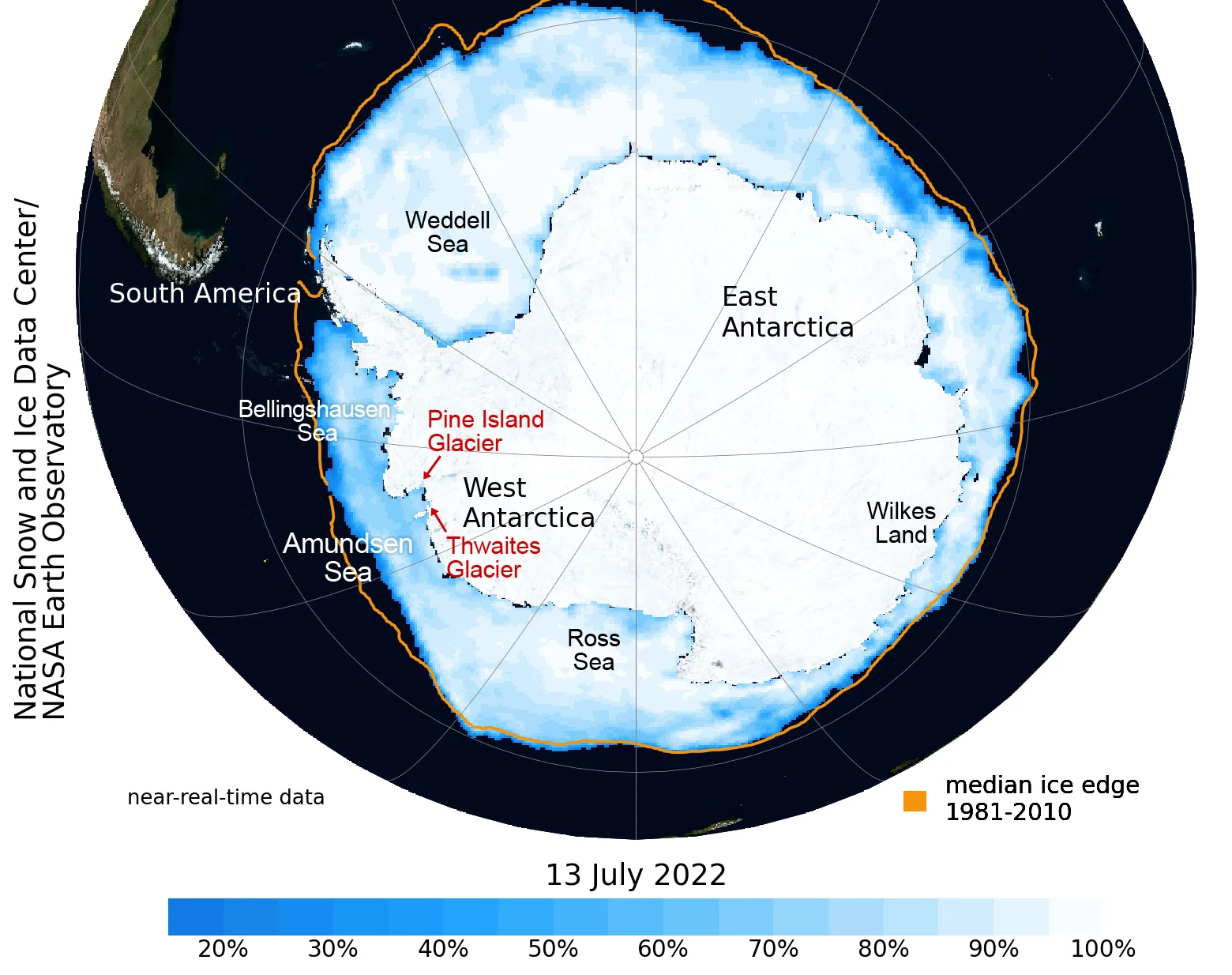

Sea ice off the Wilkes coast (where the Conger Ice Shelf collapsed on March 30) has apparently not been feeling the impact of the warmer conditions observed there. Meanwhile, despite cool continental winds blowing off West Antarctica over the Amundsen Sea, sea ice extents there have been low for this time of year.

Sea ice extent and concentration for July 13, 2022 are plotted on this map. Across the Amundsen Sea and Bellingshausen Sea, extents are well below average for this time of year (orange line), and the darker colours of the plot reveal how sparse the ice is in those regions of the Southern Ocean. (NSIDC/NASA EO/Scott Sutherland)

Researchers now believe they know the reason for the exceptionally low Antarctic sea ice extent we saw back in February and March.

In a study published in April, they described a combination of factors, such as the cooler ocean temperatures across the equatorial Pacific Ocean due to La Nina, the warm ocean temperatures experienced elsewhere in the southern hemisphere, and a strong region of low atmospheric pressure off the coast of West Antarctica known as the Amundsen Sea Low. Together, these factors set up a weather pattern that caused more heat to flow from lower latitudes towards the south pole, resulting in more sea ice loss.

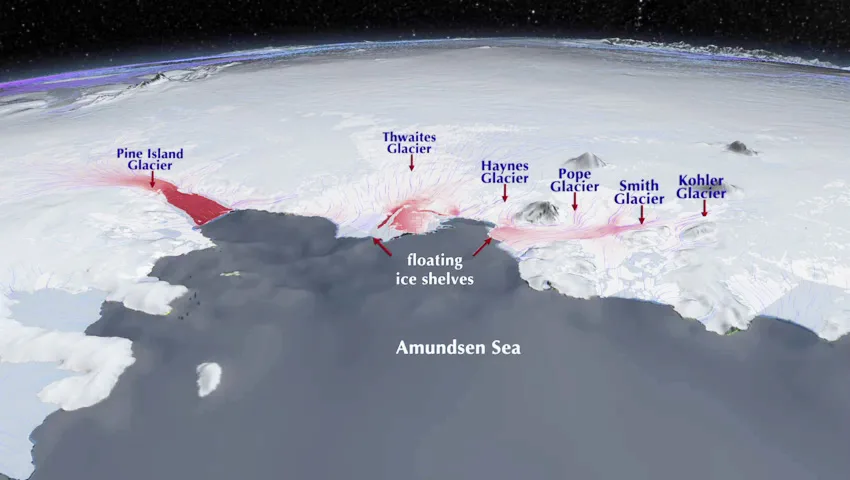

West Antarctica is experiencing more than just sea ice loss. Glaciers in that region of the continent have been particularly vulnerable to the effects of global warming. New research has found that the Thwaites and Pine Island glaciers, both located along the coast of the Amundsen Sea, are now retreating at a rate faster than anything seen in the past 5,500 years.

This illustration shows the locations of the major glaciers along the Amundsen Sea in West Antarctica. The red colour overlay represents satellite data showing where the speed at which the ice is moving towards the sea is increasing on a yearly basis. (NASA/JPL-Caltech)

The risk of the Thwaites Glacier collapsing has prompted scientists to nickname it the Doomsday Glacier.

Thwaites, the widest glacier in the world, contains enough water to raise ocean levels by roughly 60 centimetres if it were to collapse into the sea. The larger danger, though, comes from how Thwaites is tied to the glaciers around it, helping to pin them in place, and how it is connected to the larger mass of the West Antarctic Ice Sheet.

If Thwaites were to completely collapse — a real risk if we do not shift the course of climate change — it would clear a pathway for the surrounding glaciers to follow. Ted Scambos, one of the world's leading experts on Thwaites, says that this could drag the rest of the West Antarctic Ice Sheet along with it. Such a catastrophe would result in three to four metres of sea level rise, displacing millions of people from coastal communities around the world.

(Thumbnail image courtesy National Snow and Ice Data Center)