‘Groggy climate giant’ slowly awakening from under Arctic Ocean

"These results are important because they indicate substantial but slow climate feedback," says one researcher.

Frozen for thousands of years in Arctic permafrost, billions of tons of carbon and methane are slowly being released into the atmosphere due to rising temperatures. A new study shows that while the release is slow, continued thawing of this permafrost will significantly impact Earth's climate.

Over the past two centuries, human activities have released around 1.8 trillion metric tons of carbon dioxide into the environment. As a direct result of this, global temperatures have risen by about 1°C since the 1800s. Based on only the most optimistic of projections, that warming is expected to reach at least 2°C by the end of this century.

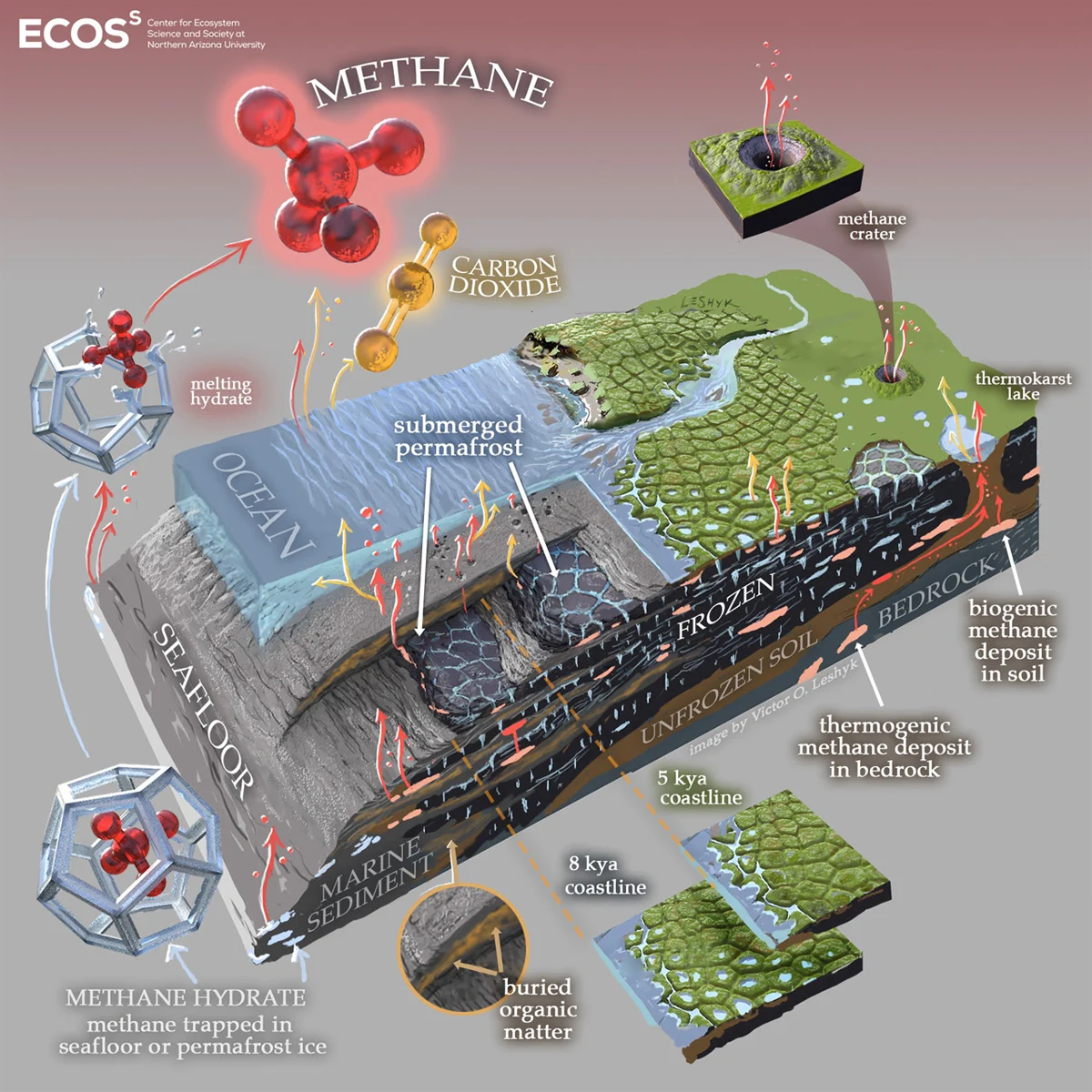

While the world's nations continue to burn fossil fuels, there is a slumbering 'climate giant' in the Arctic. Permafrost—soil that remains frozen all year long—contains immense reservoirs of buried organic matter, as well as pockets of methane trapped in ice (methane hydrates). As these regions thaw, that trapped methane more easily reaches the surface. Meanwhile, microbes become active in the warmer soil and begin breaking down that organic matter, producing carbon dioxide and methane in the process. As these greenhouse gases are added to the atmosphere, warming becomes even worse. This is known as a climate feedback loop.

This diagram shows an artist's impression of subsea and coastal permafrost, with its abundant carbon and methane deposits. Credit: Victor Oleg Leshyk, Northern Arizona University

Knowing exactly how big this carbon reservoir is and how quickly these processes can occur is very important. Scientists need this information to make accurate predictions of how Earth's climate will change in the years to come.

With novel research, an international team of scientists focused their attention on subsea permafrost.

"Subsea permafrost is really unique because it is still responding to a dramatic climate transition from more than ten thousand years ago," Sara Sayedi, the Brigham Young University PhD student who co-led the study, said in a university press release. "In some ways, it can give us a peek into the possible response of permafrost that is thawing today because of human activity."

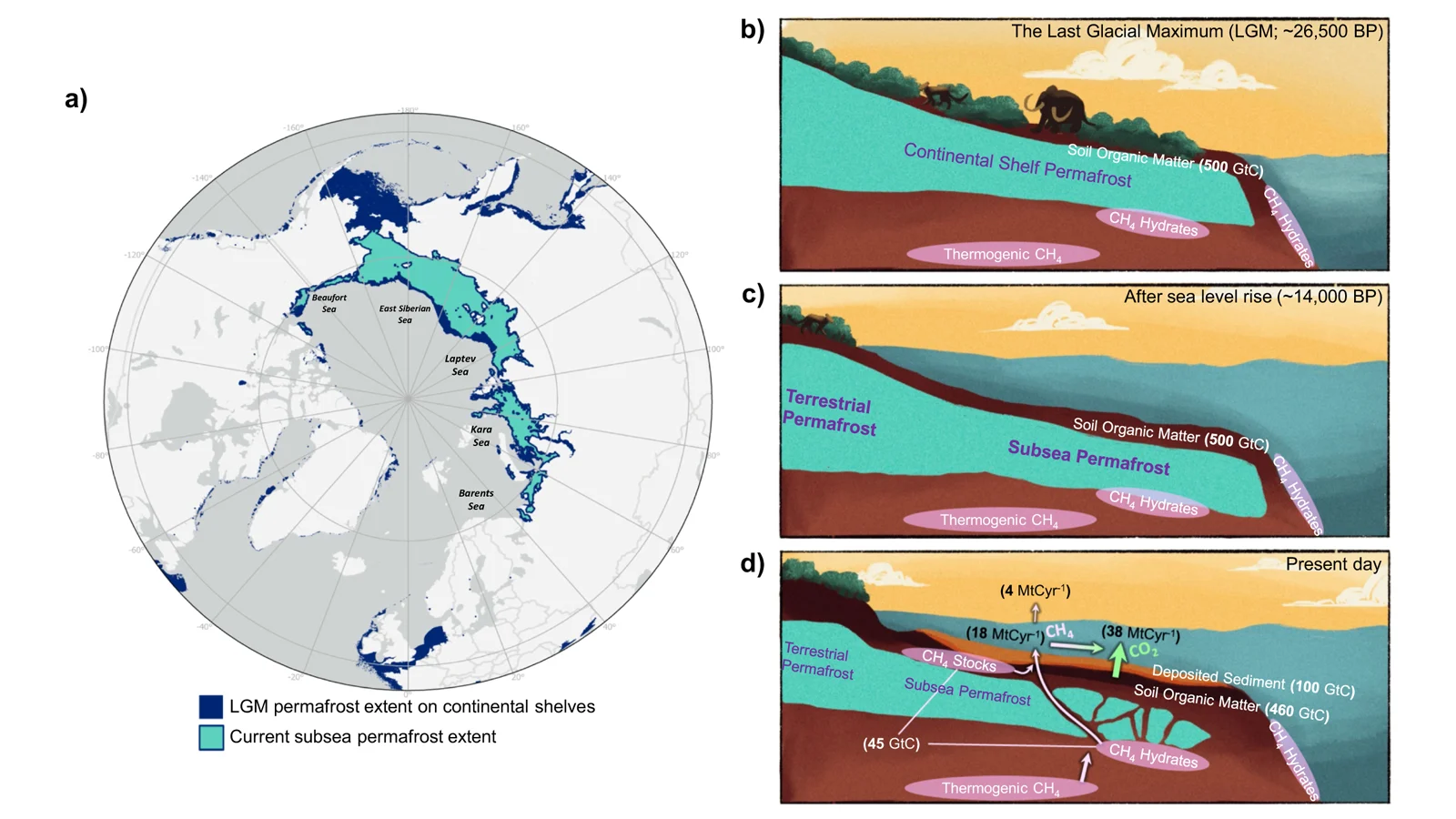

During the last glacial period, tens of thousands of years ago, much of North America, Europe, and Asia were covered in ice several kilometres thick. With all of that frozen water locked up on land, Earth's oceans were much smaller and more shallow than they are today. In the north, this meant that exposed shores of that shallower ocean became permafrost.

The extent of subsea permafrost during the last glacial maximum (left, dark blue) and current extent (left, light blue), plus the processes of permafrost formation during the LGM, and its submersion over the past 14,000 years. Credit: Sayedi, et al./IOP

As Earth warmed and those glaciers retreated, rising sea levels submerged that permafrost under the frigid waters of the Arctic Ocean. Over those tens of thousands of years, the ocean water, which is only a few degrees above freezing, has been very slowly thawing the subsea permafrost along the northern continental shelves.

During the course of their research, Sayedi and her team combined numerous sources — a method known as 'expert assessment' — to estimate how much buried carbon and methane are likely trapped in these subsea layers. They also produced an estimate for how much is already being released into the atmosphere from this source.

Based on their study, the carbon stored in these regions of subsea permafrost represents the equivalent of over 2 trillion metric tons of carbon dioxide (plus 60 billion metric tons of methane). That is more carbon than has been emitted by all human activity since the start of the Industrial Revolution.

The coastline of the Bykovsky Peninsula in the central Laptev Sea, Siberia retreats during summer, when ice-rich blocks of permafrost fall to the beach and are eroded by waves. Credit: P. Overduin/IOP

Fortunately, there is some small amount of good news from this study. Their results indicate that Arctic methane and carbon deposits might not be the 'hair-trigger bomb' that we fear they are.

As of 2019, the amount of excess carbon dioxide released each year reached around 40 billion metric tons. The annual release of methane was a little over 600 million metric tons per year. By comparison, the thaw of subsea permafrost only releases around 140 million metric tons of carbon dioxide and 5.3 million metric tons of methane per year. So, while the total amount of carbon stored in subsea permafrost is substantial, the current rate of release is slow.

"These results are important because they indicate substantial but slow climate feedback," Sayedi said. "Some coverage of this region has suggested that human emissions could trigger catastrophic release of methane hydrates, but our study suggests a gradual increase over many decades."

Watch below: Thawing permafrost splits trees, causes massive 'slump'

This is not to say that the rate of thaw will always remain slow. The rate the researchers computed is based on the natural warming these permafrost regions have experienced over the past 14,000 years. As the climate continues to warm due to human activities, this rate will undoubtedly increase. By how much remains to be seen (and much more study is needed in this area).

Based on their expert assessment, however, Sayedi and her team believe that the large-scale release of carbon and methane from subsea permafrost is something that would happen over the next few centuries, rather than all at once.