Historic Amazon rainforest fires threaten climate, raise risk of new diseases

The checkerboard of forest edges increases the potential points of contact between humans and wildlife, which in turn increases the likelihood of viral transmission and the emergence of novel human diseases.

By Kerry William Bowman, University of Toronto

The fires in the Amazon region in 2019 were unprecedented in their destruction. Thousands of fires had burned more than 7,600 square kilometres by October that year. In 2020, things are no better and, in all likelihood, may be worse.

According to the Global Fire Emissions Database project run by NASA, fires in the Amazon in 2020 surpassed those of 2019. In fact, 2020’s fires have been the worst since at least 2012, when the satellite was first operated. The number of fires burning the Brazilian Amazon increased 28 per cent in July 2020 over the previous year, and the fires in the first week of September are double those in 2019, according to INPE, Brazil’s national research space agency.

Despite the surge in fires, international attention has waned in 2020, likely due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Yet the degradation of the Amazon rainforest has profound consequences from climate change to global health.

Global climate implications

The Amazon rainforest covers approximately eight million square kilometres — an area larger than Australia — and is home to an astounding amount of biodiversity.

It helps balance the global carbon budget by absorbing carbon dioxide from the atmosphere, and plays a key role in the global water cycle, stabilizing global climate and rainfall. A nine nation network of Indigenous territories and natural areas have protected a massive amount of biodiversity and primary forest.

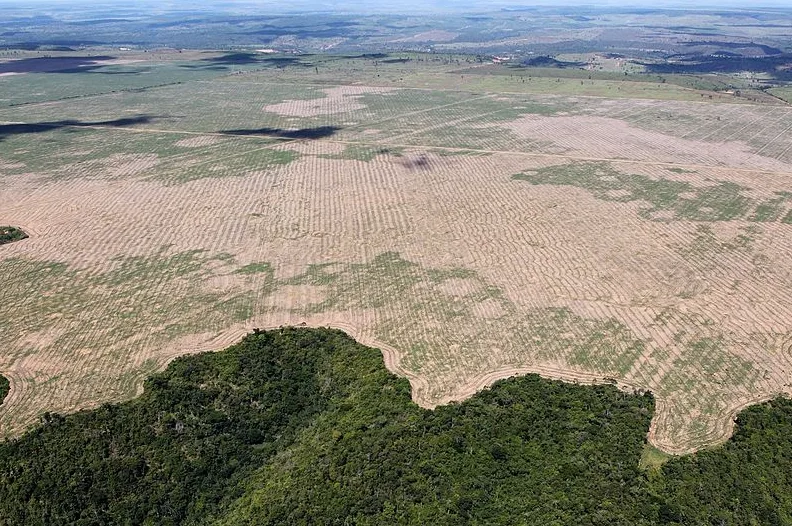

Yet these lands are under siege. As of 2019, an estimated 17 per cent of the Amazon’s forest cover has been clear-cut or burned since the 1970s, when regular measurements began and the Amazon was closer to intact.

Clear-cutting in the Gurupi Biological Reserve and the Caru and Alto Turiaçu Indigenous Lands, in Maranhão, Brazil. Credit: Felipe Werneck/Ibama, Wikimedia Commons

As the rainforest bleeds biomass through deforestation, it loses its ability to capture carbon from the atmosphere and releases carbon through combustion. If the annual fires burning the Amazon are not curtailed, one of the world’s largest carbon sinks will progressively devolve into a carbon faucet, releasing more carbon dioxide than it sequesters.

While the global impacts are dire, the local impacts of these fires are also significant. Persistent poor air quality, which extends far into Brazil and other regions of South America, including in metropolitan centres like São Paulo, can lead to health problems.

As roads are built and forests are cleared for timber production and agriculture, a checkerboard of tropical forest edges is created. These destructive activities can lead to rapid extinctions and a severe loss of species richness anywhere that human encroachment occurs.

Many researchers predict that deforestation is propelling the Amazon towards a tipping point, beyond which it will gradually transform into a semi-arid savanna. If the deforestation of the rainforest continues past a threshold of 20-25 per cent total deforestation, multiple positive feedback loops will spark the desertification of the Amazon Basin.

Global health implications

Zoonotic diseases, like SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19, are on the rise. Understanding the root causes of these spillover events that move viruses from animals to humans gives us insight into how to prevent future zoonotic outbreaks. The degradation and fragmentation of tropical rainforests such as the Amazon may be a key factor in this process.

The checkerboard of forest edges increases the potential points of contact between humans and wildlife, which in turn increases the likelihood of viral transmission and the emergence of novel human diseases. Intact forests and high levels of biodiversity, on the other hand, can provide a “dilution effect” associated with a lower prevalence and spread of pathogens.

Prevfogo/Ibama Indigenous brigades fighting a forest fire in the Porquinhos Indigenous Land, in Maranhão, Brazil. Credit: Terra Indígena Porquinhos/ Wikimedia Commons.

Read more: Why bats don't get sick from the viruses they carry, but humans can

The present pandemic may well have had an environmental genesis. Maintaining the Amazon’s current high level of biodiversity is vital, both for the health of the global ecosystem and because, otherwise, the Amazon could become a future hotspot of emerging diseases. When we protect the global ecosystem, we also protect ourselves from emerging zoonotic diseases.

Interventions are complex, but the protection of Indigenous territories, the restoration of already degraded lands and, most importantly, continued international awareness of political dynamics and consumer choices, all offer us ways to avert oncoming tragedy. If we do not take a longer view of this pandemic and look upstream for drivers and causes, pandemics will continue to emerge.

This article was co-authored by research assistants Benjamin Thomas Rabishaw, Jevithen Nehru, Samuel Dale and Sumana Dhanani.

Kerry William Bowman, Adjunct assistant professor, bioethics and environment, University of Toronto

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.