Heat waves are increasing, and some neighbourhoods will be worse off

New research explores how different parts of Toronto will be disproportionately impacted by extreme heat.

Toronto has sweltered this summer under the oppressive heat of 19 days over 30°C as of Aug. 30, with many of those days having humidex levels tipping above 40°C.

In the 1990s, Toronto typically saw only around 12 days at this temperature in the summer. New research shows that the city will see closer to 30 days at 30°C in the next decade and around 60 by the year 2100.

Heat waves are an extremely dangerous type of weather that is becoming increasingly common in Canada. The June 2021 heat dome in British Columbia has been cited as the deadliest weather event in Canadian history with over 600 deaths being directly related to the abnormal temperatures.

Provincial authorities found that of the people that perished, the majority did not have air conditioning.

The federal government issues heat warnings for the City of Toronto when there are two consecutive days of 31°C or higher (with nighttime temperature remaining above 20°C), or when the humidex is over 40°C for two or more days in a row.

But even when the weather hits these benchmarks, some parts of the city see hotter conditions than others and impact residents in disproportionate ways. Those regions may have fewer resources to adapt to more frequent and severe heat waves in the future, Karen Smith, an assistant professor at the University of Toronto, told The Weather Network.

Sunny day at Sugar Beach, Harbourfront, in Toronto. (Katrin Ray Shumakov/ Moment/ Getty Images)

Smith is part of a team researching how the various regions of Toronto handle heat waves and the indicators of vulnerability to extreme heat. The team is using a heat index that was published in a study used to analyze heat waves in Vancouver, and Smith explained that “hot days” in the project refer to days with maximum temperatures of 30°C or greater.

While their research hasn’t yet been published, many of their insights are very relevant to the summer Toronto has just experienced.

Outside of the city’s official heat warnings, meteorologists categorize hot conditions as a heat wave when temperatures exceed 30°C for three consecutive days or longer.

Before the 2000s, Toronto typically saw only one or two heat waves per year, but this could climb up to six heat waves each summer at the end of this century, according to Smith.

“That's almost the whole summer. In Toronto, we've got two months of summer vacation for kids in school and about every day is going to be greater than 30°C,” Smith said.

Watch below: Extreme weather is changing Canadians' views on the climate crisis

Some areas are more affected by extreme heat than others

How these extreme temperatures impact residents depends on a number of factors, including where exactly in the city you live.

Smith said one of the most significant indicators of a neighbourhood’s vulnerability to heat waves is the amount of tree cover. In addition to the shade that trees provide, they also release water vapour, which lowers temperatures.

Shaded surfaces have been found to be up to 25°C cooler than unshaded areas.

“In older residential neighbourhoods that have lots of tree cover, we found less vulnerability to heat, whereas regions with lots of tall buildings, especially in the downtown core, there isn't much canopy cover and it isn't doing much above ground level. So we found that was a strong predictor of vulnerability,” Smith explained.

Condos cover the waterfront almost blocking views of the CN Tower in Toronto on July 30. (Steve Russell/Toronto Star via Getty Images)

The research team’s current analysis shows some of the coolest parts in Toronto include regions around the Don Valley, Rouge Park, and the Humber River Valley due to the extensive tree cover. Areas along Lake Ontario benefit from the lake’s cooling effect. Some of the warmest regions include Parkdale, the Humber River Black Creek, and the Jane and Finch area.

“These [temperatures] are clearly related to the valleys and ravines. The west side of the city tends to be more vulnerable than the east side,” said Smith.

Additionally, a 2016 study reported that heat-related ambulance calls in Toronto were 12.3 per cent higher during heat events compared to the previous or following weeks. The study stated that Toronto neighbourhoods with less than five per cent canopy cover had nearly 15 times as many heat-related calls as neighbourhoods with greater than 70 per cent tree canopy cover.

Low income and low education were demographic factors that indicated a higher risk of vulnerability to heat waves, according to the researchers. Some people with lower incomes have less access to health insurance or medical treatments. They might also have other health conditions that can potentially be exacerbated by high temperatures.

The Parkdale neighborhood is nearly empty during lockdown on June 7, 2021, in Toronto. (Ian Willms/ Stringer/ Getty Images News)

Smith noted the ability to adapt to these rising temperatures differs based on neighbourhood. For example, people in higher-income neighbourhoods can afford to install air conditioning systems, and if they own the home, they can do so without consulting a landlord.

However, renters might be in a situation where their landlord is not interested in installing air conditioning. The City of Toronto has bylaws regarding the installation and placement of window air conditioning units, which can limit tenants’ options for staying cool during the summer.

“The city is trying to overcome a few of these issues, but some of what needs to be done is at the provincial-level related to building codes. It seems like it's a complicated process to kind of update building codes around cooling because it's not something that all buildings already have,” said Smith.

Expanding green infrastructure

The City of Toronto has numerous strategies to try and improve sustainability and resilience as the climate continues to change. In 2019, Toronto released its first Resilience Strategy that outlines goals and actions for the city in the coming years, particularly in light of climate change and growing inequities.

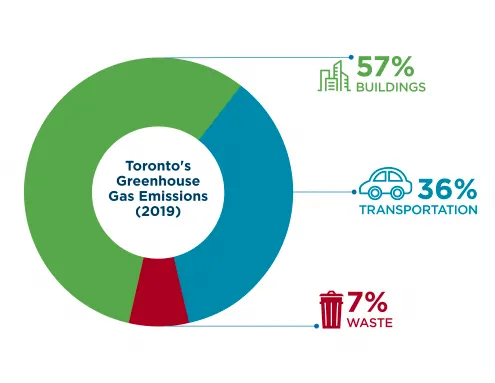

This figure from 2019 indicates that 57 per cent of greenhouse gas emissions in Toronto came from homes and buildings, primarily from burning natural gas for heating, 36 per cent were from transportation, with the majority being personal vehicles, and seven per cent were from waste, mainly from landfill emissions. (City of Toronto)

Heat is cited as one of the main hazards that the city aims to build more resilience against, which will be done through infrastructure and building solutions. Strategies that will be used to accomplish this include centralizing resources for a city-wide flood planning and prioritization tool, updating existing flood mitigation programs, and scaling efforts to advance sustainable infrastructure.

The TransformTO Net Zero Strategy also outlines a plan to reach zero greenhouse gas emissions by 2040, which is one of the most ambitious targets in North America. Some of the action items in this strategy include retrofitting existing homes and buildings to reduce energy consumption and ensuring near zero emissions for all new construction.

Don River and the Don Valley Parkway in Toronto. (Orchidpoet/ iStock/ Getty Images Plus)

In November 2021, the city council reaffirmed the target of 40 per cent tree canopy cover by 2050, which is expected to provide services such as energy savings, pollution removal, and carbon sequestration that are valued at $55 million annually.

However, a recent article from The Toronto Star points out that despite millions of dollars in spending, tree canopy coverage only increased by 0.4 per cent in Toronto from 2008 to 2018.

“A closer look at the numbers reveals that canopy coverage may have peaked in 2014. It’s been on the decline since,” the article stated.

“In 20-50 years down the road, I hope there will be some adaptation measures that help mitigate the projected extreme temperatures,” said Smith.

Thumbnail image: View of Toronto Downtown from Riverdale Park on a sunny summer day. (Katrin Ray Shumakov/ Moment/ Getty Images)