Mysterious 'Dark River' may flow for 1,000 km underneath Greenland

Models suggest that melting water from the centre of Greenland’s ice sheet could flow through a subglacial valley and exit into the ocean along the northern coast of the country.

Greenland’s vast ice sheet covers nearly 80 per cent of the country and is the second-largest body of ice on Earth, after Antarctica. Given the enormous size of Greenland’s ice sheet, it is especially vulnerable to warming atmospheric temperatures and is rapidly undergoing changes that researchers are racing to document.

A study published in The Cryosphere considers how the canyons, trenches, and valleys within and underneath Greenland’s glaciers formed and what they could look like. The researchers state that this study is a thought experiment to speculate what could be underneath Greenland and suggest that there could be a river, nicknamed the ‘Dark River’, inconspicuously flowing for more than 1,000 kilometres from the deep interior of the massive continental glacier.

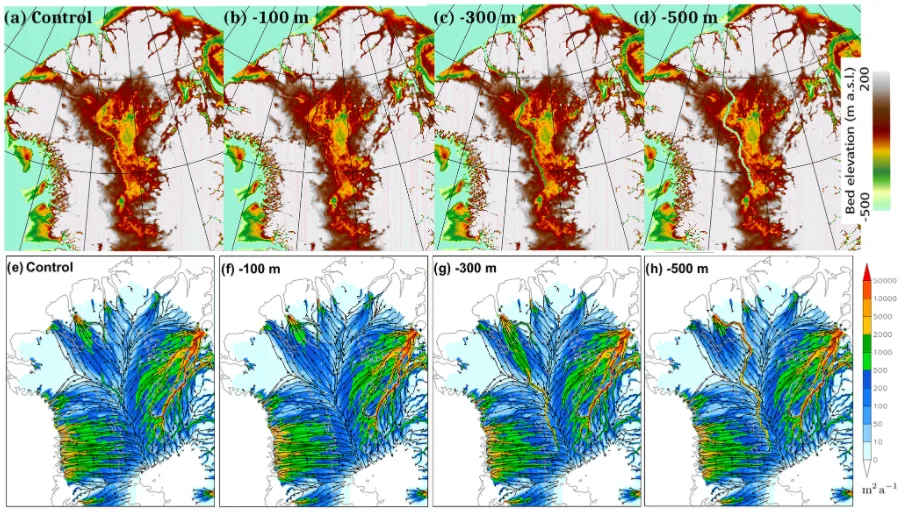

Ice-penetrating radar surveys and models of Greenland’s bedrock indicate that there could be a long valley, but the researchers are uncertain if it is continuous or broken into segments. To explore what would happen if deep parts of the ice sheet’s centre began to melt more quickly, they created simulations for valleys that were both continuous and segmented.

The models showed that an open valley would stretch over 1,000 kilometres from the interior out to the Petermann Fjord on Greenland’s northern coast. The valley is described as being “relatively flat” with elevations that range from 250 to 500 metres below sea level. “[The valley] follows a path near the interior ice divide that roughly intersects the east and west basal hydrological basins,” the researchers say in a press release.

Simulations showing fixed valley base elevations relative to sea level (red) and basal water flux magnitude and streamlines for north Greenland (blue). Credit: Chambers et al., The Cryosphere, 2020. (CC BY 4.0)

The researchers also note that the length of time that the valley has potentially existed for is unclear and say that it could have developed over a “long” period of time since the valley’s flatness is consistent with the structures of “long-term active waterways.” The sheer weight of the ice sheet would have most likely made the valley’s base uneven because it released inconsistent levels of pressure as it formed, which is why the researchers are particularly curious about the valley’s relative flatness.

RELATED: Earth's deepest canyon could be flooded by a massive melting glacier

Due to the obvious constraints that prevent researchers from investigating the interior of the ice sheet, the study notes that both radar and aerial data availability are a source of significant uncertainty with respect to their Dark River hypothesis.

“The results are consistent with a long subglacial river,” Chambers says, “but considerable uncertainty remains. For example, we don’t know how much water, if any, is available to flow along the valley, and if it does indeed exit at Petermann Fjord or is refrozen, or escapes the valley, along the way,” said Christopher Chambers, a scientist at Hokkaido University and one of the study’s authors.

A scientist in west Greenland using a ground-penetrating radar device. Credit: Silvan Leinss/ Wikimedia Commons. (CC BY 4.0)

While the prospect of a hidden river flowing for 1,000 km underneath Greenland is both whimsical and eerie, this research reflects the massive scale of Greenland’s ice sheet and the amount of frozen water it holds.

“This could introduce a fundamentally different hydrological system for the Greenland ice sheet. The correct simulation of such a long subglacial hydrological system could be important for accurate future ice sheet simulations under a changing climate,” said Ralf Greve, another scientist at Hokkaido University that authored this study.

Climate models indicate that global sea levels could rise about 6 meters (20 feet) if Greenland’s ice sheet completely melts, which would force the millions of people currently living in coastal communities to seek refuge inland.

Thumbnail credit: Adobe Stock