Earth's days are getting longer due to melting polar ice

Global warming is slowing the rotation of Earth.

New research has confirmed that our days are getting longer due to global warming.

Earth's rotation is anything but constant. It slows down and speeds up due to a number of different factors, and this has a direct impact on the length of our days.

The strongest influence over time has been tidal friction with the Moon, which slows the planet's rotation enough to add an average of 2.4 milliseconds to our day every century. Smaller effects are seen from powerful earthquakes and friction with the atmosphere, as well as the rate of spin of Earth's solid iron core, and the 'rebound' of the mantle towards the poles seen since the end of the last ice age.

However, another factor has emerged that could soon rival even the Moon's influence on the rotation of our planet — global warming.

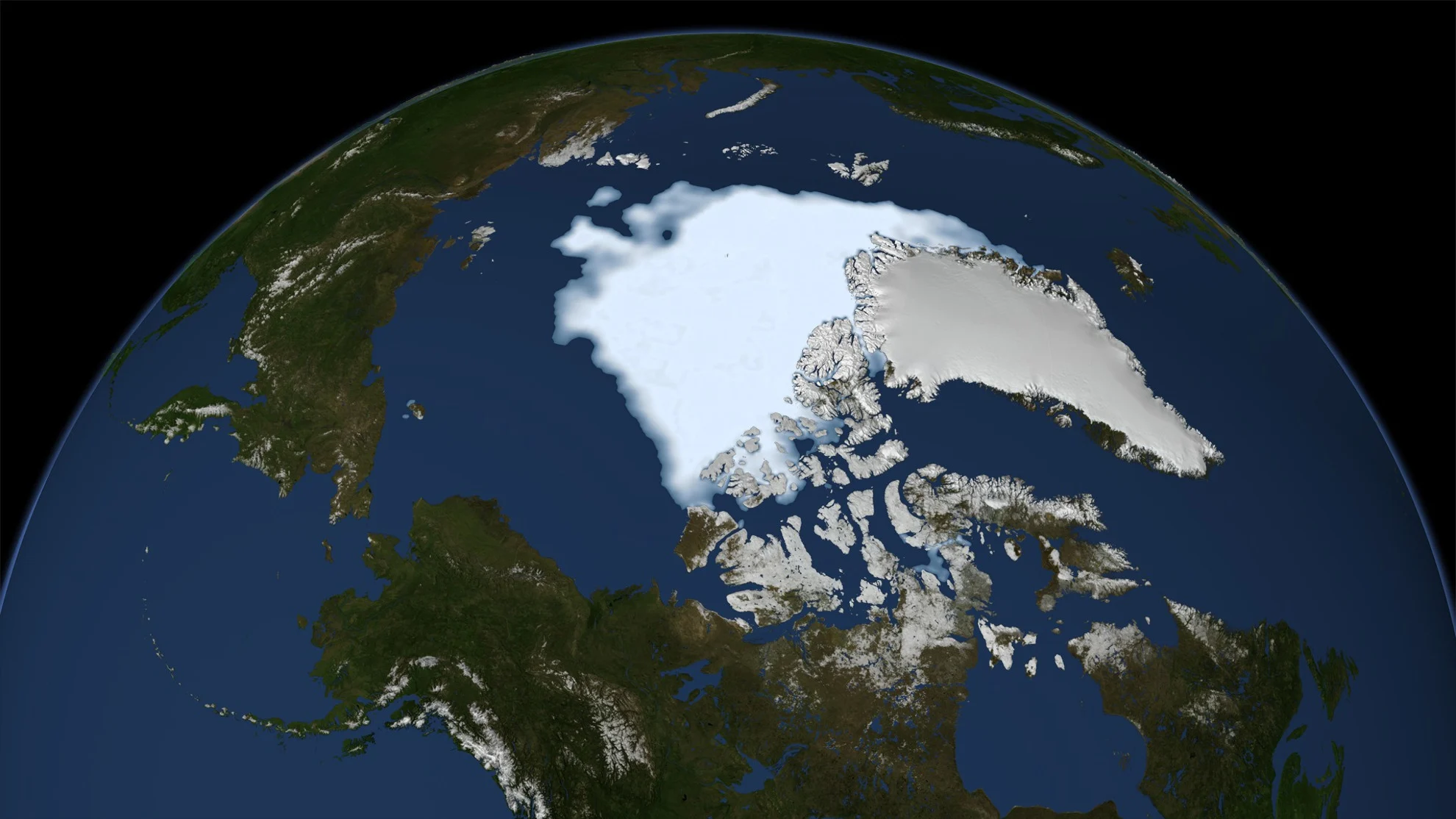

As we continue to burn fossil fuels, the greenhouse gases released into the atmosphere cause our planet's temperature to rise. This results in more ice loss from the poles — both from ice sheets and sea ice — with the meltwater then spreading out into Earth's oceans.

The overall impact of this is that millions of tons of mass are shifting from the poles towards the equator.

READ MORE: Melting ice caps put the need for bizarre 'negative leap second' on hold

In the same way that a spinning figure skater can slow their rotation by extending their arms out away from their body, this shift in mass away from Earth's axis slows the rotation of the planet.

New research using data from NASA's Gravity Recovery and Climate Experiment (GRACE), and the follow-up NASA/GFZ GRACE-FO mission, has confirmed this.

"In barely 100 years, human beings have altered the climate system to such a degree that we're seeing the impact on the very way the planet spins," study co-author Surendra Adhikari, a geophysicist at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory, said in a NASA press release.

The GRACE and GRACE-FO missions both measured gravity anomalies. The amount of gravity that an orbiting satellite experiences at any moment is based on exactly how much mass is directly between it and the centre of the planet. For example, GRACE and GRACE-FO would experience a bit more gravitational pull when passing over the Rocky Mountains than they would over the middle of the Atlantic Ocean. The data from these missions was used to construct the highest resolution gravity map of our planet ever made.

The GRACE mission's gravity map of Earth. (NASA)

From this, scientists tracked the shifting of magma in the Earth's interior and the movement of groundwater through aquifers. Perhaps the most important result, though, measured how the melting of ice sheets, glaciers, and sea ice was altering the mass-balance of our planet.

In this new study, data from GRACE and GRACE-FO was combined with measurements taken throughout the 20th century. This allowed the researchers to relate the movement of mass due to groundwater and melting ice to the variations in the length of our days, from the year 1900 through until 2018.

For the 100 years between 1900 and 2000, they found that the rate at which Earth's days grew longer due to the loss of ice and shifting of water ranged between 0.3 to 1.0 milliseconds per century.

However, after the year 2000 — at the same time that the world was seeing an increase in the rate of ice loss from polar regions — the rate of change in the length of Earth's day jumped up to 1.33 milliseconds per century.

These changes in Earth's rotation, and thus the length of our day, can accumulated to the point where we need to add extra time to our clock, via a 'leap second'. They can also impact the function of GPS satellites and even space missions to other planets.

"Even if the Earth's rotation is changing only slowly, this effect has to be taken into account when navigating in space," said co-author Benedikt Soja, a Professor of Space Geodesy (using satellite data to studying the geometry, gravity, and spatial orientation of Earth) at ETH Zurich.

Over the millions of kilometres travelled on the way to Mars, for example, a small error in the timing of the launch due to the changing spin of our planet could result in a spacecraft being off target by hundreds of metres when it arrives, potentially putting the entire mission in jeopardy.

Stabilizing the rise in Earth's temperatures, specifically by transitioning away from fossil fuels to clean energy sources as quickly as possible, can slow this effect over time.

However, if emissions continue to rise, the researchers say the rate of day-lengthening could reach as high as 2.62 milliseconds per century, surpassing the influence of tidal friction from the Moon.

"We humans have a greater impact on our planet than we realize," Soja said, "and this naturally places great responsibility on us for the future of our planet."

(Thumbnail image courtesy NASA's Goddard Scientific Visualization Studio)