Ocean warming off Antarctica could trigger rapid sea-level rise

On a warming planet, most of the ice field covering West Antarctica would be lost, researchers conclude.

We’ve all heard the saying: “The best way to predict the future is to study the past.” And that’s exactly what climate scientists are doing to predict future global sea-levels.

A study led by Chris Turney, Professor of Earth and Climate Science at the University of New South Wales in Australia, explains that during the last interglacial period, about 129,000-116,000 years ago, Antarctica experienced a massive thaw that caused sea levels to rise up to three metres in some parts of the planet. According to Turney, temperatures across the polar oceans were less than 2°C above current values, and an ocean temperature rise of less than 2°C led to that scenario.

This is a cause for concern in present-day, as we continue to see temperatures rise at an unprecedented rate in the polar regions -- thus causing ice to melt more rapidly and subsequently contributing to rising sea-levels. On a warming planet, most of the ice field covering western Antarctica would be lost, researchers conclude.

An aerial photo of the Getz Glacier ice shelf front on November 5, 2016, reveals water so clear that you can see some underwater portions of the ice shelf, including two cavities being hollowed out near the water line. Source: NASA Operation Ice Bridge photo.

RECORD-BREAKING TEMPERATURES

This past February 6th, temperatures measured at the Argentine research base of Esperanza reached 18.3°C. That was officially the highest temperature measured in the southern continent on record, exceeding the previous record set in March 2015 with a high of 17.3°C. The surprising thing is that a few days later, on February 9th, the thermometer at the Argentine base of Marambio, located on Seymour Island, registered an even higher temperature of 20.75°C.

These temperatures are not common, and although they are certainly eye-openers, scientists investigating climate change in Antarctica have pointed out that they cannot be directly attributed to anthropogenic climate change affecting the region.

What really worries those investigating the metamorphosis that Antarctica is experiencing this decade, is the rise in ocean temperatures as it relates to accelerated ice melt and its potential contribution to sea-level rise.

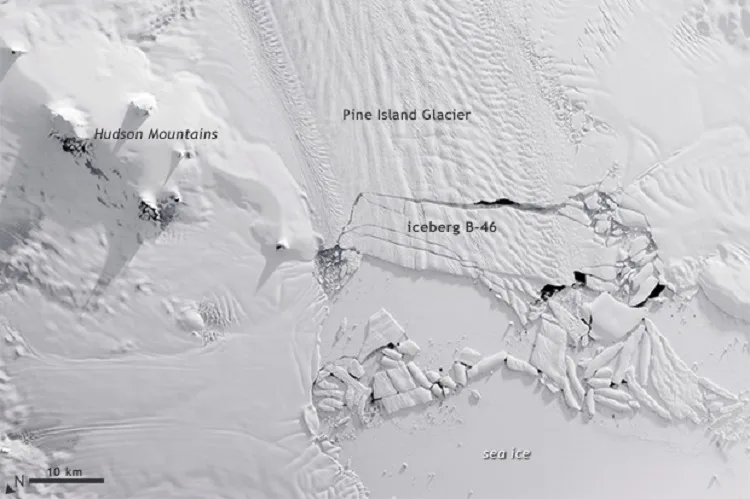

The Pine Island Glacier drains part of the West Antarctic Ice Sheet into the Amundsen Sea via Pine Island Bay. Recently, the glacier has been calving massive icebergs, such as this one, designated B-46, captured in a NASA satellite image from November 7th, 2018. Image by NASA Earth Observatory.

WHY WESTERN ANTARCTICA IS MOST VULNERABLE

Unlike the East Antarctic ice sheet, which is mainly on high terrain, the West Antarctic ice platform rests on a seabed. It is bordered by large areas of floating ice that protect the main section of the ice field. As ocean water warms and travels through the lower cavities of these platforms, the ice below melts, reducing the thickness of the platforms, making the central ice sheet highly vulnerable to higher water temperatures.

While most scientists investigating Antarctica drill vertically into the ice core to extract samples, Turney's team used a different method; the horizontal analysis of the ice core, based on isotope data collected from samples of volcanic ash, gases and DNA from bacteria trapped in the ice. The rate at which the ice fields of West Antarctica melt indicates that this region of the continent is especially vulnerable to ocean warming. In addition, this mantle of ice rests on oceanic waters that continue to warm year after year.

A look at the future of Antarctica’s ice melt, via numerical simulations conducted by the research team, shows the clear impact ocean warming would have on Antarctic ice sheets several centuries from now. For example, if we saw a warming of 2°C over the next thousand years, sea level would rise around 3.8 metres. The simulations also indicate that over the next 200 years, ice fields would melt first, with sea level subsequently increasing.

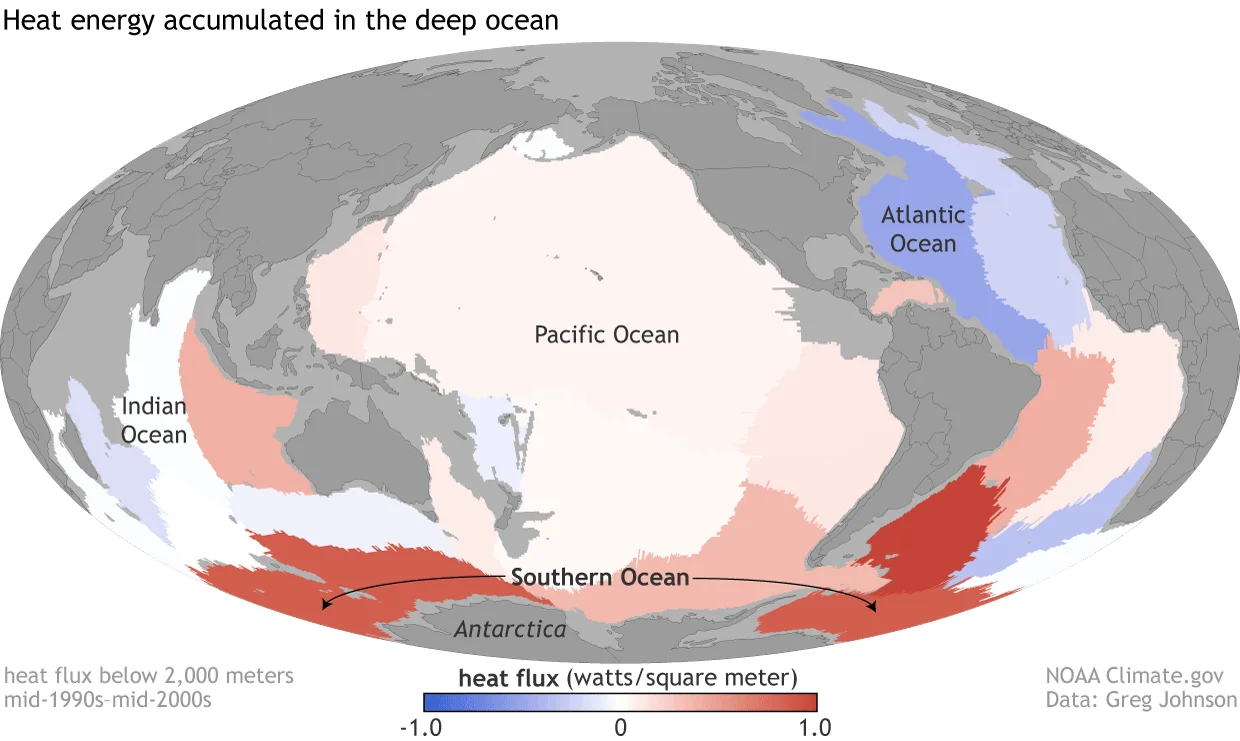

Map 1 : Heat flux into the deep ocean (below 2,000 meters) between the mid-1990s and the mid-2000s, based on repeat ship cruise data. Places where the deep ocean gained heat are red; places where it lost heat are blue. NOAA Climate.gov map, based on data provided by Greg Johnson.

Scientists also worry if this continuous rise in sea temperatures will end up affecting other areas of Antarctica. If so, the excess energy could accelerate ice melt beyond a tipping point that would eventually amplify ice melt even further while leading to much higher sea levels across the globe.