Parts of B.C., Quebec could be underwater if the planet keeps warming

Many Canadians that live in coastal communities will face rising sea levels and flooding in the future if global greenhouse gas emissions are not drastically reduced.

Climate Central, a nonprofit research group, collaborated with several international institutions to create visual representations of flooding in major coastal cities if the planet warms to 3°C above pre-industrial levels.

The world has already warmed 1.2°C (± 0.1°C) and ongoing conversations at COP26 are exploring what humanity can do to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and limit global warming.

Over 90 per cent of the temperature rise associated with these emissions are absorbed by the oceans. The two main mechanisms behind sea level rise are increased amounts of water melting from frozen landscapes, glaciers, and ice sheets, and the thermal expansion of water molecules as they warm and take up more space.

The rising tepid waters will eventually force themselves on land and of the 50 cities that were featured in the study, three Canadian cities made the list: Quebec City, Vancouver, and Victoria.

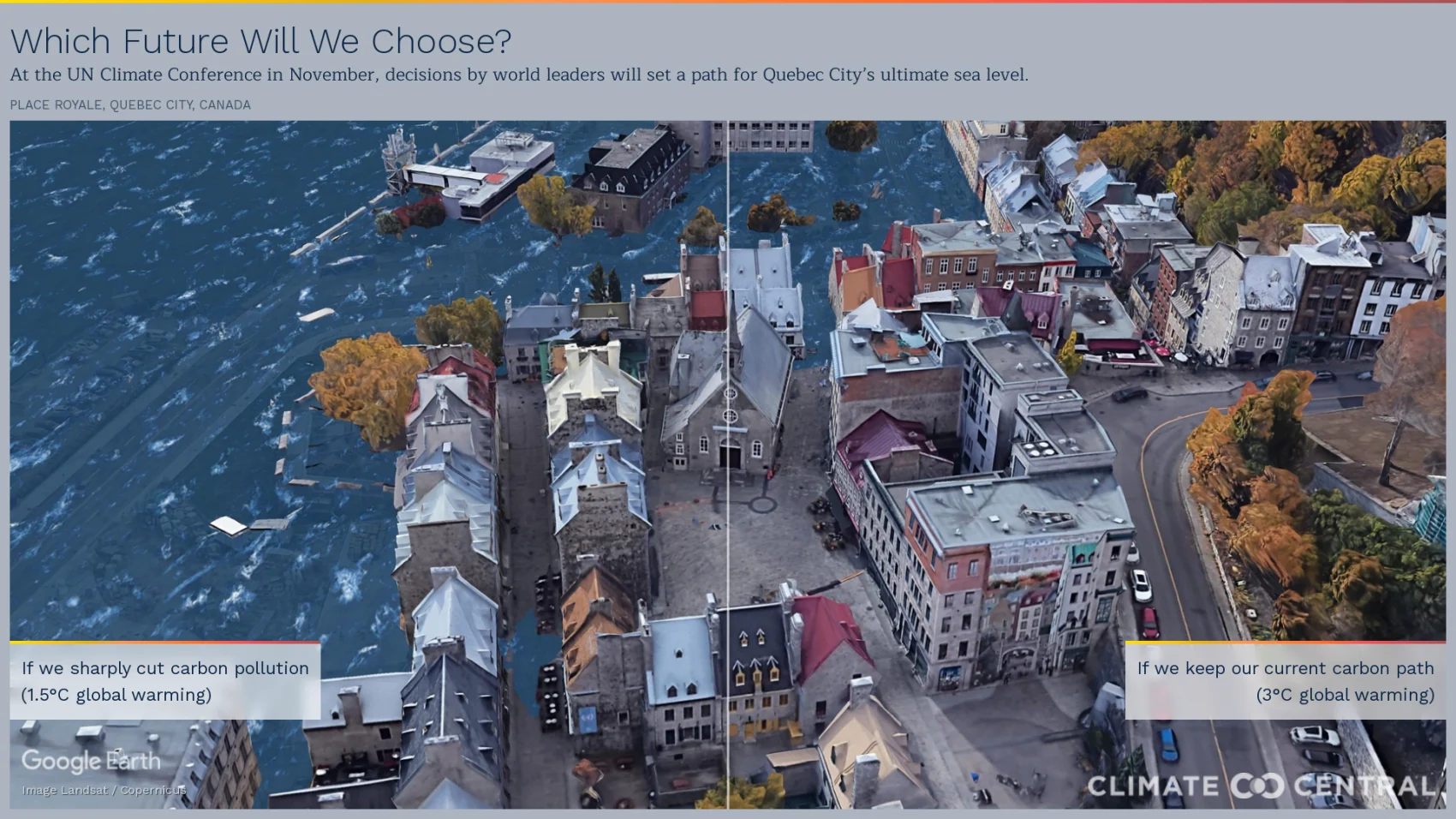

In the East Coast, the study looked at Place Royale in Quebec City and projected high levels of flooding, even if warming is limited to 1.5°C. A French settlement was first built here in 1608 and much of the city’s history is reflected in buildings and architecture that are situated close to the St. Lawrence River. If 3°C of warming occurs, Climate Central’s illustrations show that many roads and homes will be flooded.

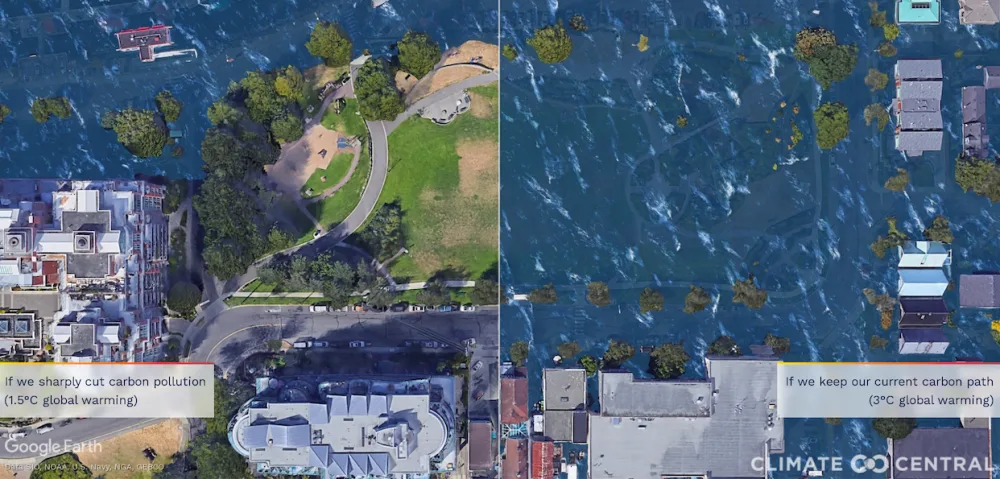

In British Columbia, the projections suggest significant flooding in southern regions in a 3°C warming scenario, including places such as the H.R. MacMillan Space Center, the Legislative Assembly of B.C., Fisherman's Wharf Park, and B.C. Place.

Climate Central has stated that global warming will stop around 1.5°C if we cut pollution in half by 2030. If present-day policies remain in place and no additional regulations are implemented, Climate Action Tracker projects a global temperature rise of 2.7°C above pre-industrial temperatures.

King tide on Vancouver's seawall in November 2018. (Submitted by Edwin Poulston)

FUTURE SEA LEVEL RISE IN BRITISH COLUMBIA

Roughly 80 per cent of B.C’s population lives within five kilometres of the coast. Kees Lokman, an associate professor at the University of British Columbia, says that some parts of the province are “very close to sea level” and are at risk of flooding. Lokman told The Weather Network that sea level rise projections are changing as new research is released, but current numbers suggest a rise of 0.5 metres by 2050 and 1.2 metres by 2100.

When asked what could occur if emissions continue on a business-as-usual scenario, Lokman said: “That would probably result in migrations or relocation, I would say of populations to areas higher ground or places where the risk of flooding would be lower, and giving space back to ecosystems to kind of adapt with changing water levels over time.”

While the projections are alarming, a mass inland migration is the worst-case scenario, and Lokman has said we can minimize impacts by being proactive and implementing certain projects and infrastructures.

Many promising projects include nature-based methods that are centred around Indigenous knowledge. This includes expanding and protecting wetlands and salt marshes so they can act as natural buffers against flooding.

Living dykes are another strategy that can be implemented globally. These types of dykes have a lower gradient on the seaward side so plants and salt marshes can grow on it as sea levels rise, which helps reduce the force of waves.

“[Living dykes] would allow coastal ecosystems to inhabit that edge of the dyke, which is much better than our typical dyke that has kind of a three-to-one slope and doesn't really allow for coastal ecosystems to inhabit those spaces.”

“Change will be disruptive. It won’t be ‘win-win’ for everyone. But not all change has to be bad,” Lokman said in a UBC press release.

“If we’re proactive, the disruptions to our lives will be much less than if we ignore the issue.”

Thumbnail credit: Climate Central