River piracy, dust storms occurring in the Yukon as the climate warms

Locations that have been visited by generations of First Nations communities no longer look like they once did as landscapes change with the warming climate.

“That is a dry looking river bed.”

This was how Amber Berard-Althouse described the view from the top of Sheep Creek Trail looking out onto the ’A’ą̈y Chù’, otherwise known as Slim’s River.

Dry was an understatement. All that was left of the river is water trickling down from the mountain creeks that have flowed into the valley. What makes this even more disconcerting is that just four short years ago the ’A’ą̈y Chù’ used to be a vast, swollen river and the main water source for Kluane Lake.

So what happened?

“We watched it happen right in front of our eyes,” says Berard-Althouse who is a Public Outreach Education Officer with Parks Canada at Kluane National Park and Reserve.

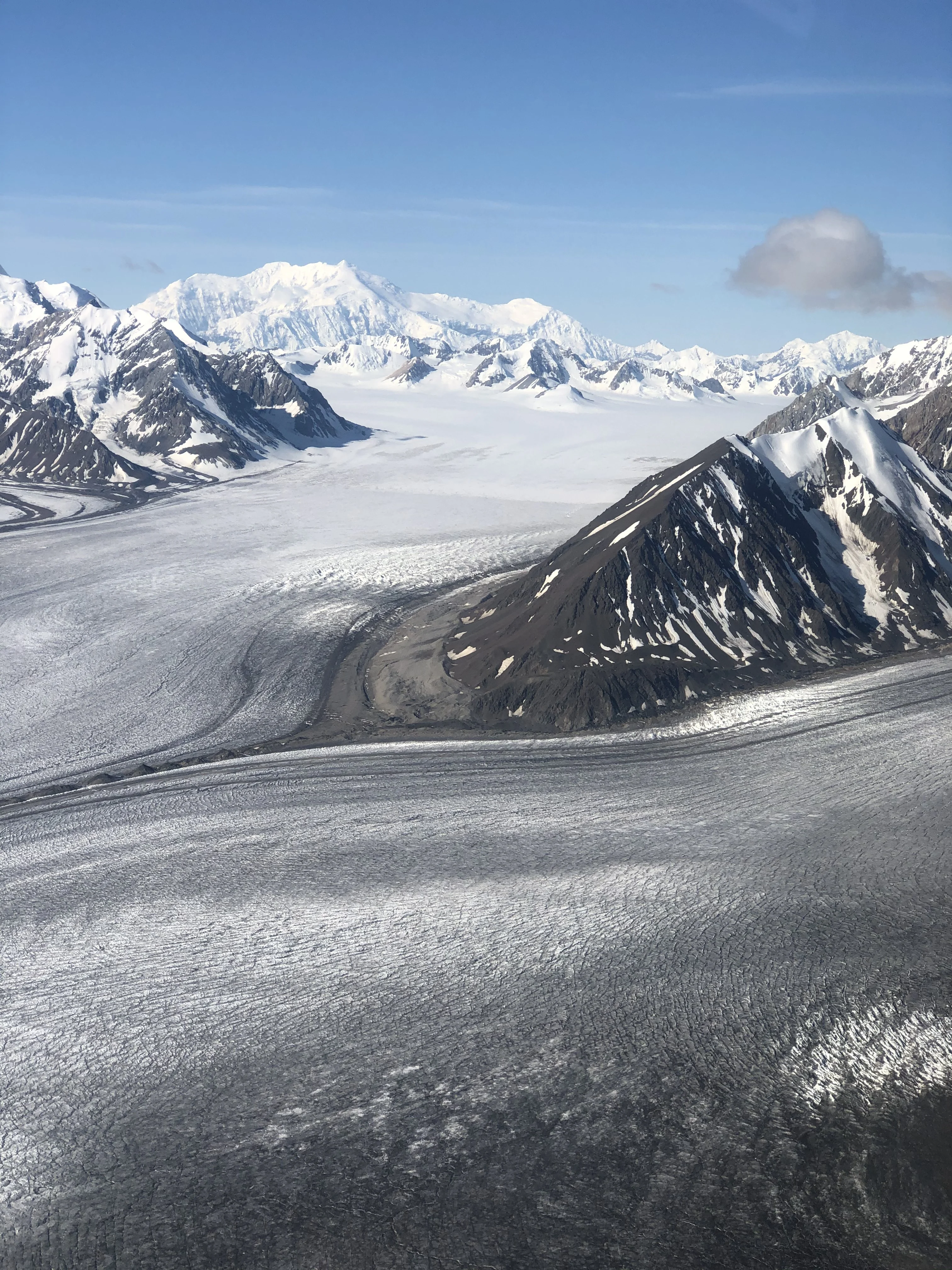

“Approximately 23 kilometres down the valley is the toe of the Kaskawulsh Glacier and the start of our icefields. Underneath the Kaskawulsh Glacier, we have two river channels, the ’A’ą̈y Chù’ and the Kaskawulsh River, which are both fed by the glacier. The glacier [started] to recede, and all of a sudden the water gets rerouted down only the Kaskawulsh River.”

Glaciers in the Kluane Icefield. Credit: Mia Gordon

The glacier eventually shrank enough that a narrow channel opened between the two lakes. Since the Kaskawulsh River was lower, gravity pushed all the water in that direction.

According to geologist Geoff Bond of the Yukon Geological Survey, this is the first time something like this has happened in over 300 years, which is a process that is now known as river piracy.

The disappearance of the ’A’ą̈y Chù’ has caused a devastating domino effect. Just down the valley is Kluane Lake, the largest lake in the Yukon and an important resource for the Indigenous Peoples that live in the area, but in the last few years, the lake level has dropped by two metres.

For Berard-Althouse, who is Southern Tutchone, this has had a personal impact on her and her family.

“A couple of years ago, after the river dried up, I went fishing with my great-uncle and we went out on Kluane Lake to a location where he learned how to net fish with his mother, my great-grandmother. I was able to learn a lot and come to this historical place, this ancestral place. We set this net, and by the end of the day we went back to collect our fish, thinking we were going to have a lot of fish.”

That wasn’t the case. When they pulled up the net, there was only one fish.

“I just saw my uncle. He looked completely confused. You could just see the disappointment and sadness in his face.”

This is just one example of the impacts that disappearing and changing waterways have had on the Indigenous Peoples that call the Kluane region home.

Right after the changes happened to the lake, boats weren’t able to launch out of Destruction Bay, which prevented people from fishing.

On top of that, the silt and dust from the mountains that were previously buried deep in the ’A’ą̈y Chù’ now have nowhere to hide. Berard-Althouse tells us there have been dangerous dust storms on the nearby Alaska Highway that have forced cars to pull over until they pass.

Kluane National Park and Reserve. Credit: Mia Gordon

As climate change grips the Kluane region, Indigenous Peoples have been forced to adapt to the changing landscape, but with how quickly the changes are happening, Berard-Althouse questions how much longer they can keep up.

“Southern Tutchone People and Indigenous Peoples in this area are super resilient and have been adapting to the environmental changes and external factors in this area for a long time. The thing is, is the changes are happening so quickly now that it is hard for us to keep up.”

Berard-Althouse explained to us that First Nations culture is orally passed down from generation to generation. The locations that are visited for hunting and fishing have also been passed down to family members year after year, but with the changes that are happening now, sharing this information has become next to impossible.

Despite being forced to adapt to the changing climate, Berard-Althouse tells us she is still hopeful for the future, especially because there are numerous governments working together to try and protect Kluane National Park and Reserve.

Kluane National Park and Reserve is a UNESCO World Heritage Site and is cooperatively managed by Parks Canada, Champagne and Aishihik First Nations, and Kluane First Nation. These groups work together to create a framework to monitor Kluane’s ecological health. Through science as well as knowledge and observations from Elders, Berard-Althouse is hopeful that we can all work together to make a difference.

“I really hope to see this place be protected for future generations, for my children, for my grandchildren. I hope to show my kids the same glaciers that my ancestors walked on.”

With files from Christine Aikens