The curious case of a 'triple-dip' La Niña in a warming world

With hundreds of millions of people being affected by El Niño and La Niña events, scientists are closely studying how climate change could be playing a role.

The planet is gearing up for a “triple-dip” La Niña this winter. This is only the third time that has happened since the 1950s.

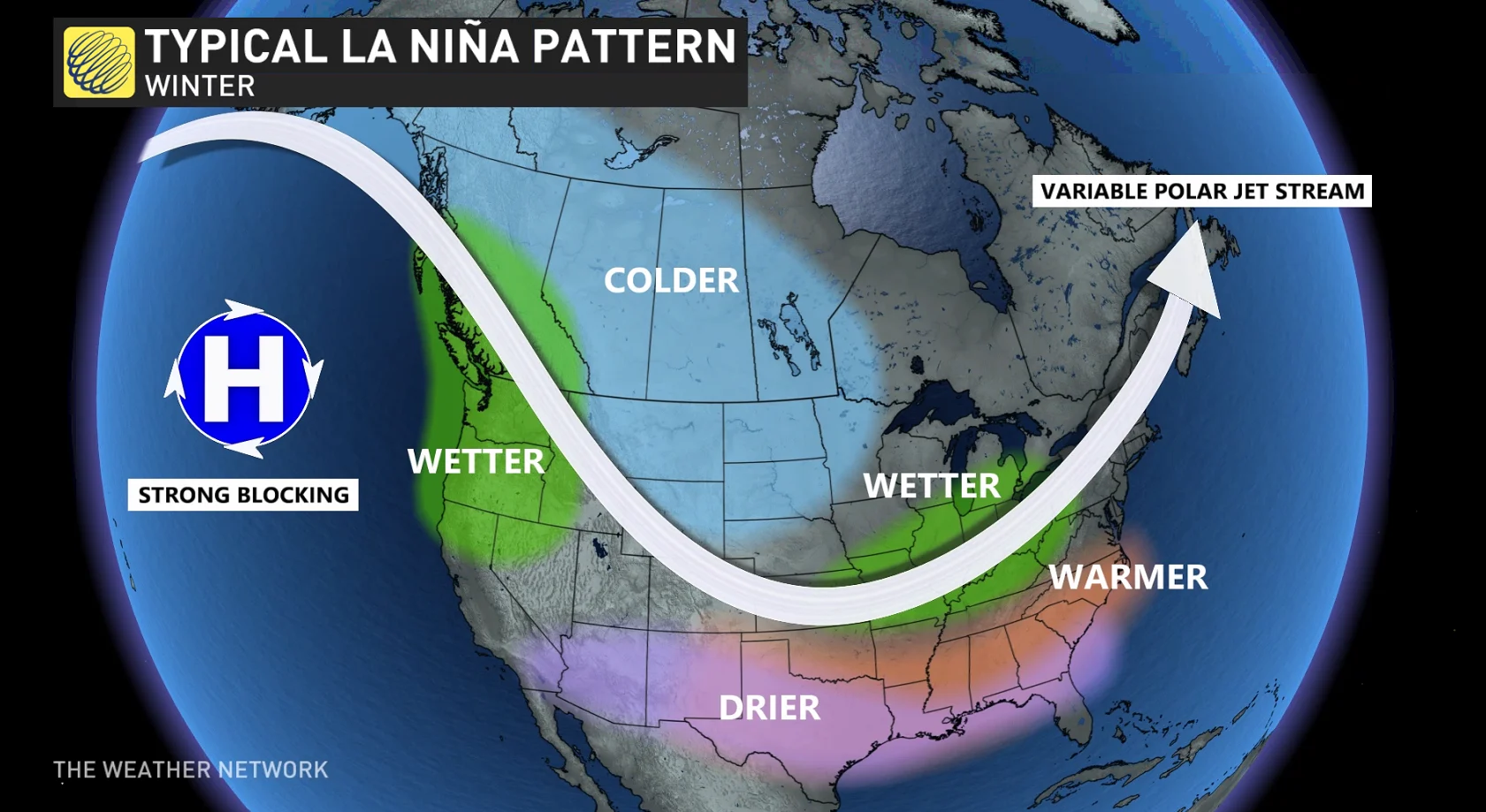

Typically during La Niña years in Canada, B.C. and the southern Great Lakes region can see above-normal levels of precipitation, the Prairies and northern Canada can be colder than usual, and the East Coast can see periods of higher than normal temperatures.

From severe drought conditions on the Pacific West Coast to severe flooding in Australia and Southeast Asia, the impacts that La Niña has on agriculture, energy, and water can cost economies billions of dollars and can be hazardous to human health.

El Niño and La Niña occur roughly every three to seven years, which is why three consecutive La Niña events are garnering so much attention. Since the past eight years on Earth will likely become the eight warmest on record, many are wondering how climate change is coming into play.

Before we dive deeper into this topic with a climate lens, it’s worth highlighting a few key concepts.

La Niña is the cool phase of the El Niño-Southern Oscillation (ENSO), which is Earth’s strongest year-to-year climate fluctuation that has far-reaching impacts.

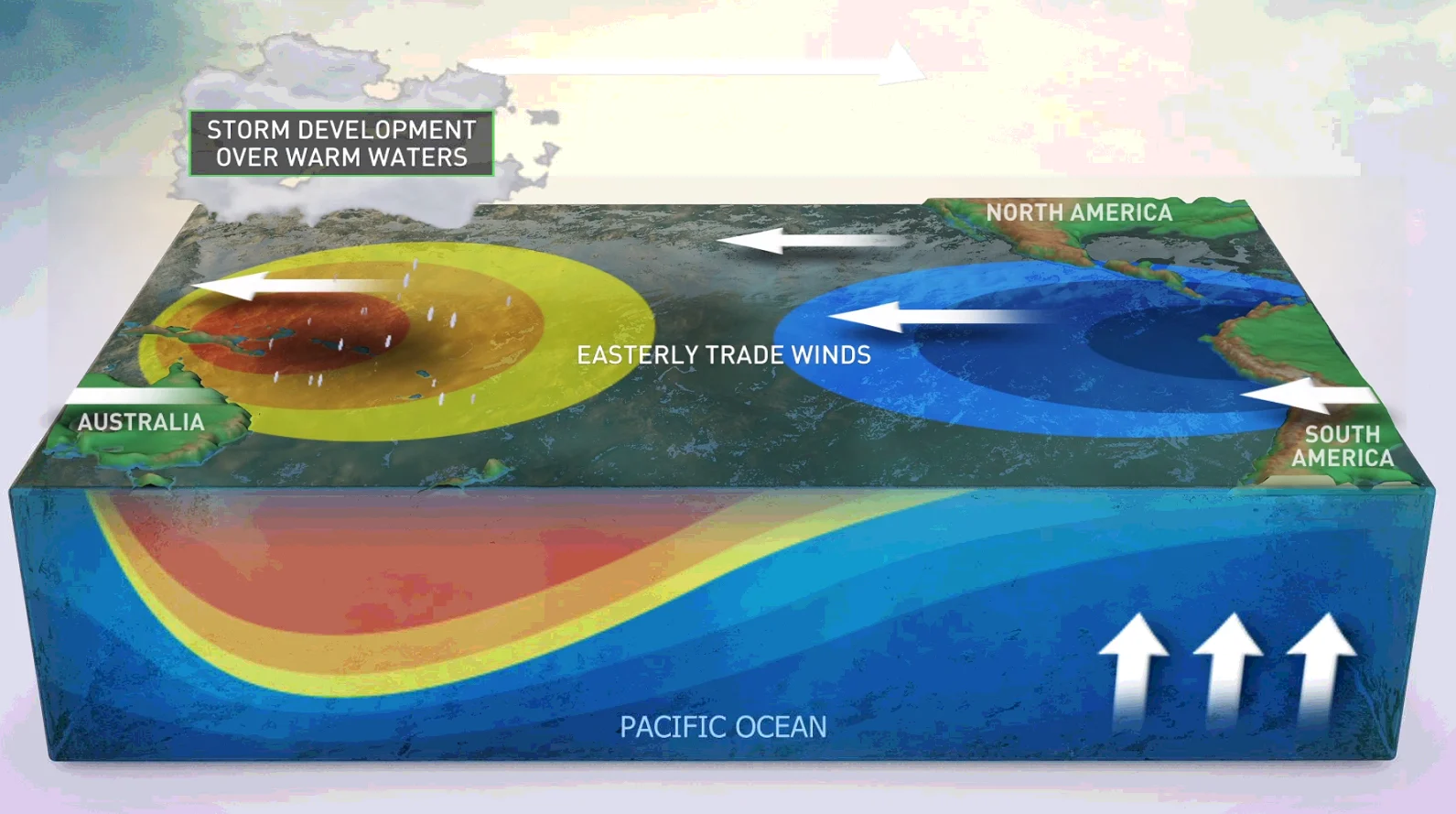

ENSO is characterized by changes in the waters in the Pacific Ocean. Normally, the winds over the equatorial Pacific Ocean blow strongly from east to west, which causes warm waters to 'pile up' in the west and cold waters to well up along the coast of South America.

During El Niño, those west-blowing winds weaken, allowing the warm water to slosh back towards the east, bringing a shift in weather patterns along with it.

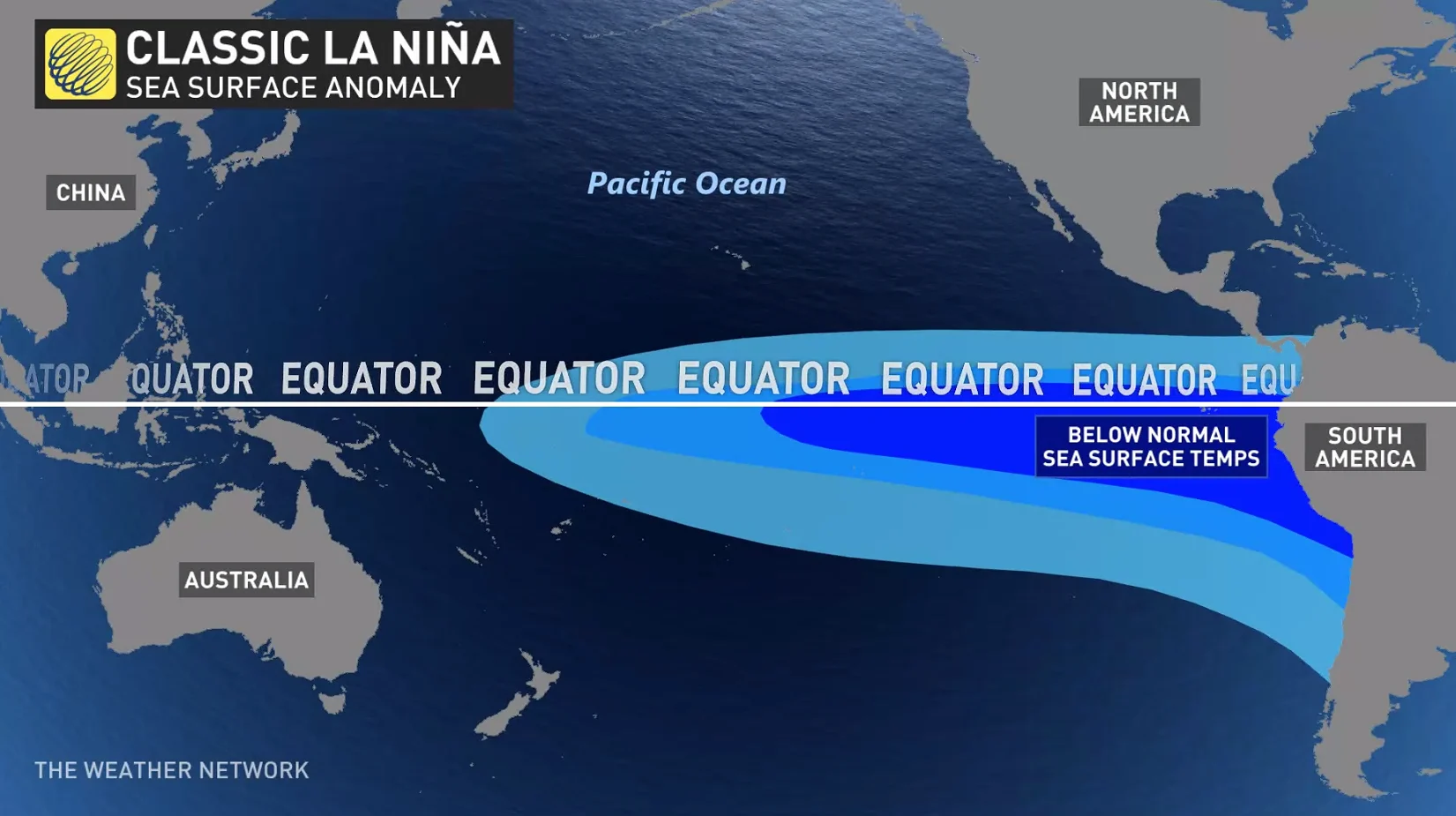

Alternatively, during La Niña, the normal east-to-west winds intensify, pushing the warm surface waters even more strongly towards the west and causing even more cold water to well up from deeper in the ocean in the east.

The atmospheric pressure over the equatorial Pacific Ocean is also affected during the different ENSO phases and can allow for the jet stream to funnel more storms across North America during the winter.

Rodrigo Bombardi, Director of Climate Science for Weather Source, explained to The Weather Network that there is uncertainty surrounding the exact influence that climate change is having on El Niño or La Niña.

Bombardi, whose Ph.D. research focused on the variability and predictability of climate models, said “it's quite rare to stay in one state for this long.”

“It's hard to find a cause and effect when comparing climate change and ENSO. Climate change is something that is happening at a global scale much slower than the cycle of El Niño or La Niña,” he added.

The correlation between human-released greenhouse gas emissions and warming oceans has been made extensively by the most accredited scientific institutions. However, the waters become murky when climate models try to separate the naturally occurring rise in sea surface temperatures during El Niño from the warming that has occurred due to climate change.

Watch below: Billions of snow crabs near Alaska have disappeared, what's going on?

Bombardi explained that there are limited historical data records for El Niño and La Niña, which makes it challenging for scientists to evaluate long-term trends. However, all weather patterns are now occurring within an atmosphere that has been warmed by human activity, which is causing storms, droughts, and other severe types of weather to worsen.

“We know that climate change will impact extreme events. So what will likely happen in the future is a drought because of El Niño or a flood because of La Niña that could be slightly worse because of climate change,” said Bombardi.

“There are some hotspots that wouldn't have otherwise experienced the persistence of the conditions that come with El Niño or La Niña. A lot of industry and human activities depend on weather conditions, so society would have to adapt to harsher conditions. For example, I'm from Brazil, where 70 per cent of the electricity comes from hydropower. So if it doesn't rain, it will affect energy production,” he added.

See also: Most of humanity just experienced the warmest October on record

Climatologists have spent years researching the possible impacts climate change is having on ENSO, with some reporting more robust findings than others.

A recent study by an international research team published in Nature Communications reports that stronger La Niña and El Niño in the eastern Pacific Ocean could start occurring between 2024 to 2036 due to rising global temperatures, which is decades earlier than originally anticipated.

The researchers analyzed ENSO since 1950 and simulated future scenarios using state-of-the-art climate models. The results indicated that warmer ocean temperatures in the eastern Pacific will cause stronger El Niño events that discharge significant amounts of heat in the upper levels of the ocean, which increases the chances of intense and prolonged La Niña events.

In an interview with Bloomberg, Richard Seager, a research professor at Columbia University’s Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory, explained that he and his research team are investigating whether climate change is increasing the odds of La Niña events. The team suspects that La Niña events could be prolonged and intensified due to the warming effect of greenhouse gases, but noted that more research is needed to make any conclusions about their research.

Some scientists warn that the most intense versions of the warm and cool ENSO phases will appear more often.

“Extreme El Niño and La Niña events may increase in frequency from about one every 20 years to one every 10 years by the end of the 21st century under aggressive greenhouse gas emission scenarios,” said Michael McPhaden, senior scientist with NOAA’s Pacific Marine Environmental Laboratory, said in an article by NOAA. “The strongest events may also become even stronger than they are today.”

While the consensus is currently unclear about the relationship between ENSO and climate change, one sentiment is certain: the rare “triple-dip” occurrence will be a key source of data that will be closely studied by scientists.

Thumbnail image: Videoblocks