What these Thwaites Glacier researchers think of its 'Doomsday' nickname

Hear from those studying the Thwaites Glacier in Antarctica about what they observed, and how it could impact our world.

You may have seen the headlines last fall: the so-called Doomsday Glacier in Antarctica is “holding on today by its fingernails.”

The official name is Thwaites, and it’s the widest glacier on Earth measuring roughly the size of Florida.

There are predictions that the ice shelf, the floating part of the glacier that holds the rest of the ice back, could collapse within five years. That would spell big trouble for the other rapidly melting glaciers nearby and already rising sea levels — hence its gloomy nickname.

It’s part of the reason why $50 million in funding was set aside by the U.K.’s Natural Environment Research Council and the National Science Foundation in the U.S. to bring together hundreds of scientists to study it under the International Thwaites Glacier Collaboration (ITGC).

READ MORE: Deep inside Greenland's melting ice cap, the situation is dire

MELT and Icefin researchers at the Thwaites Glacier in 2020. They found unusually warm Antarctic waters, even though still below freezing, have enormous potential to drive melting in the area. (ITGC)

One of those researchers is Peter Davis, a physical oceanographer with the British Antarctic Survey. Personally, he tends to avoid the “doomsday” term.

“So I'm not particularly a fan of it because I think it gives the sense that it's too late for us to do anything about it. And that's not necessarily true,” he told The Weather Network.

“Because I do think there are ways for us to combat this. I do think there are ways for us to transfer or change from a kind of carbon heavy to a more carbon neutral society. And I don't want to use the concept of doom, because doom would suggest it's too late, and therefore we should continue on the same path we're always on.”

Peter Washam is a research associate from Cornell University who is helping to compile ITGC data recently gathered on Thwaites as part of the MELT Project. He’s heard both sides of the coin when it comes to the glacier’s nickname.

Much of the Western Antarctica Ice Sheet is below sea level and susceptible to rapid, irreversible ice loss that could raise global sea-level by over half a metre within centuries. Warm water is also getting into the cracks, helping wear down the glacier at its weakest points. (ITGC)

“The discouragement comes from you don't want to sort of scare people, right? Whereas the encouragement is that this is an important problem, and we should really give it the amount of attention that it deserves,” he told The Weather Network.

Washam says the “beautiful thing” about how our world works is it self corrects, but unfortunately the time scale of self correction is much longer than modern human civilization. So while the planet may recover, the impacts of Antarctic glacier melt on the world’s population will have an impact.

“The information we gathered, and the changes we hopefully make, will take time to actually have an effect. So, at this point, it's time for sort of governments and local cities to start preparing for the influence of sea level rise, and make the changes knowing that the result won't come for some amount of time,” he said.

Once asked whether the glacier would stop melting, Washam said unfortunately no.

“The process has already sort of started. So any changes we make now are gonna take, you know, decades to hundreds to thousands of years, we don't know, for them to actually make an impact,” he said. “But in the meantime, we have to live with the way we've lived since the industrial era started.... Pumping out massive amounts of carbon emissions are now coming back and showing their ugly head.”

He says that's why collecting observations of melting glaciers at the South Pole is so important to help future climate models start in the right place.

A robot called Icefin was deployed for five missions in five days at Thwaites. Here it boasts icicles after being pulled from the Kamb Ice Stream, a glaciological feature of the Ross Ice Shelf in West Antarctica. (ITGC)

“Otherwise,... the model is always going to be wrong,” he said.

That’s partly why the researchers in the MELT Project were excited to unleash a small but powerful robot called Icefin. Designed by Britney Schmidt, who also works out of Cornell University, this robot goes under the Thwaites Glacier to give them a first-hand look at what’s happening.

What scientists found is that the pace of melting underneath much of the ice shelf is slower than previously thought, but deep cracks and "staircase" formations in the ice are melting much faster. Every year it sheds billions of tons of ice into the ocean, contributing to about four per cent of annual sea level rise.

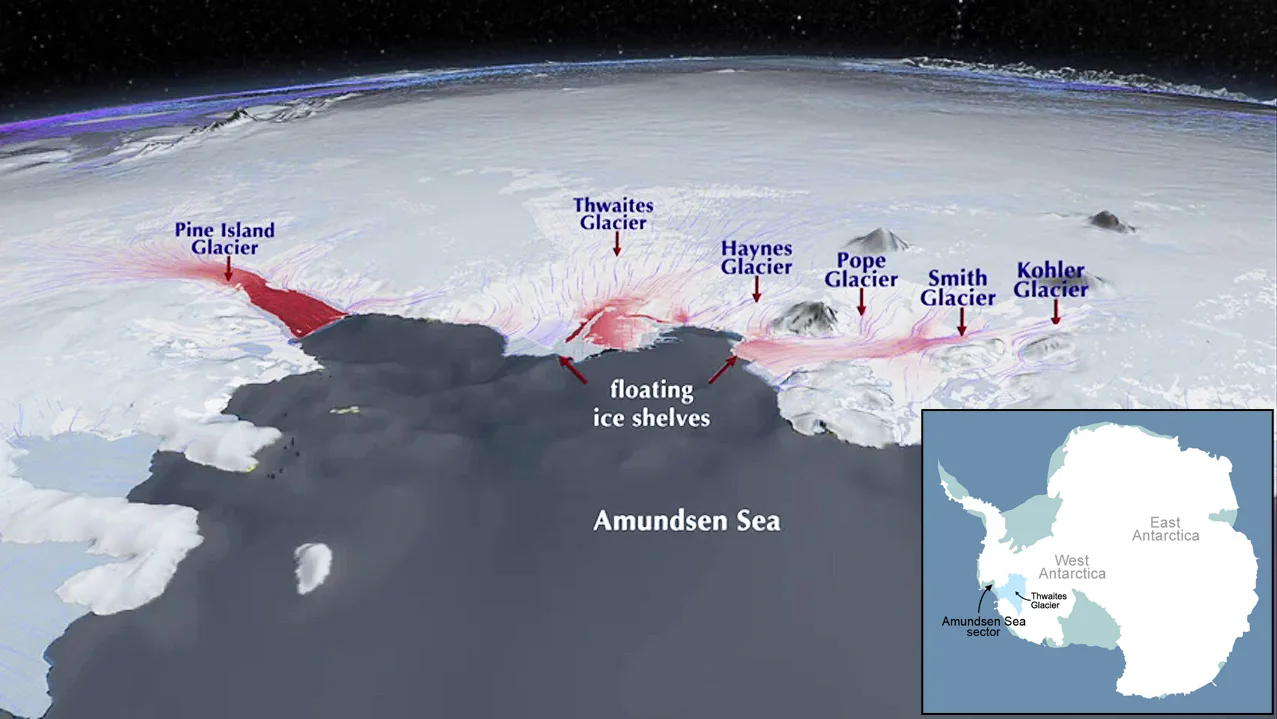

But both Washam and Davis are quick to point out it’s not just Thwaites. There are other glaciers in West Antarctica, and the much-larger Eastern Antarctica nearby, that need to be watched too as they shed ice.

These maps show the location of Thwaites Glacier, pinned between the West Antarctic Ice Sheet and the Amundsen Sea. (NASA)

“It's like adding ice cubes to the glass of water,” said Washam, adding there’s a glacier right next door to Thwaites called Pine Island that's also changing very fast.

The goal moving forward is to continue gathering more information to help inform policy across the globe about what to expect when it comes to sea level rises. But governments still need to listen, and take action.

READ MORE: East Antarctica’s Conger Ice Shelf disintegrates. What are the experts saying?

So how concerned do we need to be for the near future?

“When we're talking about collapse in the next five years, we are already talking about collapse of the ice shelf. So that's the part of Thwaites that's floating on the ocean. We're definitely not talking about collapse of the glacier, which will take many hundreds to thousands of years,” said Davis.

Physical oceanographer Peter Davis, seen here in the field, believes it's not too late to decarbonize our society. (Submitted by Peter Davis)

“That being said, it is an open question still in science as to whether we've passed a tipping point or not beyond which, even if we reduce carbon emissions, we're not necessarily going to change the trajectory of ice loss."

Davis says we may have already triggered a period of ice loss that is not easily reversed.

"We don't know that for certain though, part of why we want to get better climate projections and get the processes into the models that we know are important," he said.

"And certainly not knowing whether we passed a tipping point is no justification for not trying to decarbonize our society.”

Thumbnail image: Peter Davis on location at the Thwaites Glacier. (Submitted by Peter Davis)