Will B.C.’s famed ‘Powder Highway’ survive in a warming world?

Disturbing images of snowless ski resorts in Europe have many questioning the future of alpine skiing around the world, especially in Canada.

In a province renowned for its ski hills and mountains, one region of British Columbia has earned a name befitting its status as a skier’s paradise: the “Powder Highway.”

Along the six highways connected in a thousand-kilometre loop through B.C.’s Kootenay Rockies and interior you will find eight world class ski resorts, more than 20 backcountry lodges, and a high concentration of cat and heli skiing operations (the latter of which provide access to mountain slopes via snowcats or helicopter, respectively). It’s the largest concentration of ski services in the world, and for good reason as the powder here is considered legendary.

On average, more than 18 metres of snow blanket the nearly three million hectares that make up the region roughly 265 times the size of the city of Vancouver.

Mike Douglas, the 'Godfather of freeskiing.' (Mia Gordon/The Weather Network)

“Powder Highway is a skier's journey. It is not high-end tourism, it is not fancy resorts and five-star dinners. It is for skiers,” Mike Douglas, the “Godfather of freeskiing,” told The Weather Network. “People that want good snow and cool experience. And a real bit of B.C. that is getting harder to find. There is a vibe there that is pretty cool.”

But what would happen to the vibe of Powder Highway if the powder disappeared?

Ski resorts in need of snow

Like many other ski regions in the country and across the world, the snow here is being threatened by a changing climate. Disturbing pictures from Europe on New Year’s showed green grass where snow should be at some ski resorts, limiting access and forcing some to close entirely. Some studies have even suggested that only resorts above 2,500 metres will be operational by the end of the century, and the ski resorts that line Powder Highway are no exception.

Back in the winter of 2014-15, B.C. saw one of their worst winters on record for ski resorts. Many western ski resorts were forced to close portions of their runs, or even shut down the entire resort early due to the lack of snow. In a typical ski season, B.C. sees around 6.5 million visitors, but that season saw an almost 25 per cent decline. Many called it a wacky season — an anomaly, but that might not be entirely true according to researchers from the University of British Columbia.

The view from the slopes of the Kimberley Alpine Resort. (Mia Gordon/The Weather Network)

What the research says about the future

Professor Michael Pidwirny has been leading a team of researchers at UBC in assessing the impact climate change could have on ski resorts in North America, and the findings were grim.

“The average condition in 2050 will be like that really bad winter in 2014 and 2015. If that is the average 50 per cent of the years are even warmer than that,” Pidwirny told The Weather Network.

The team has been using spatially interpolated climate data generated by a software database called ClimateBC and ClimateNA. By inputting climate simulation models, they were able to paint a clearer picture of what snow forecasts will look like for B.C. ski resorts in the future.

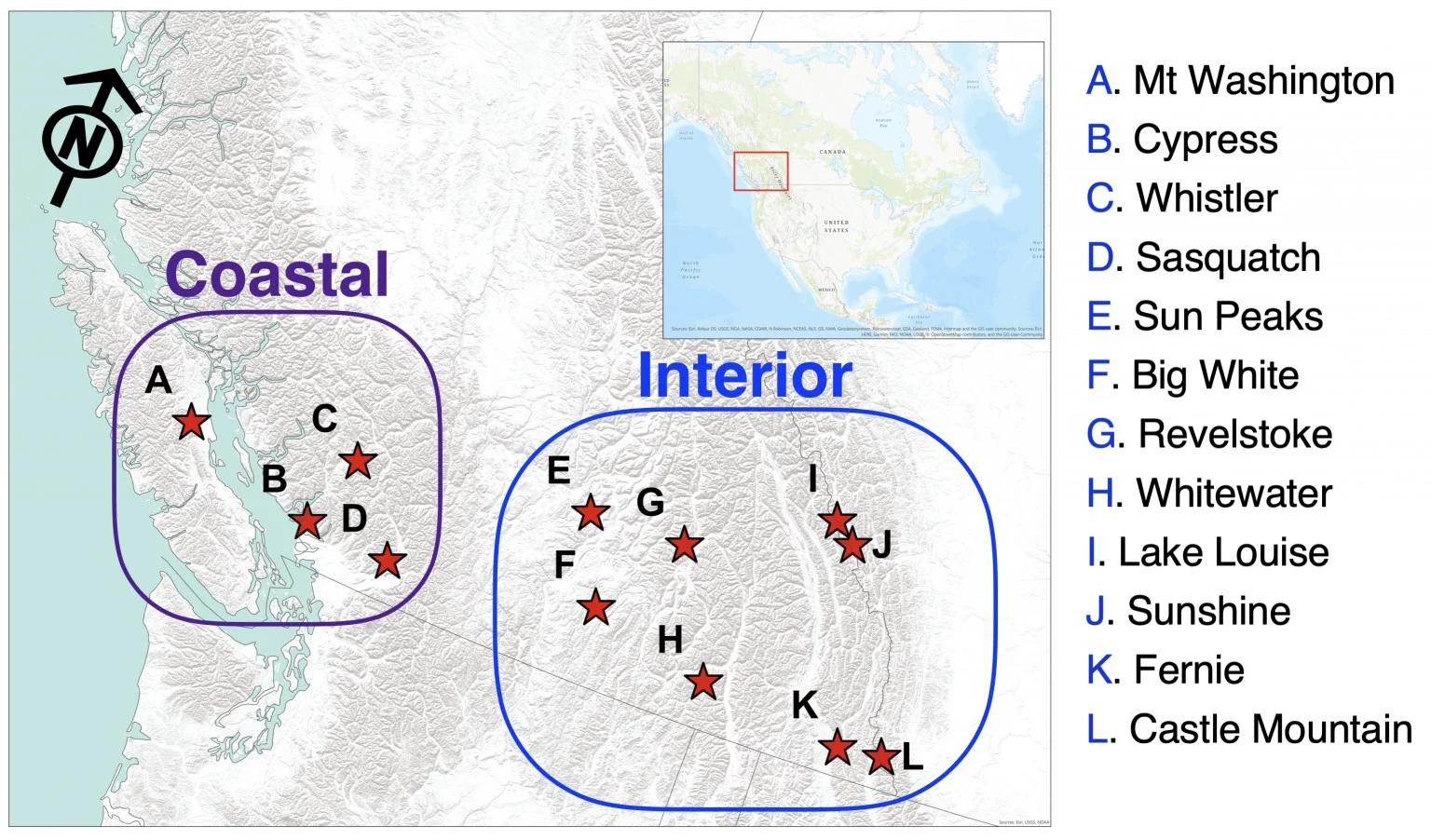

Relative location of the 12 resorts in Western Canada. (Michael Pidwirny)

“The main variables we were looking at are temperature, precipitation in the form of snow, and rainfall, because essentially as it warms up you will get less snow and more rain. Then we did some modelling of the length of the ski season,” said Pidwirny.

They mapped out their findings for best- and worst-case scenarios, best being an increase of about 2.5 C, while the worst case an increase of about 4.5 C. The models showed that by 2085, in a worst case scenario, interior resorts will see a decrease of snowfall between 26-38 per cent. This would also lead to a shorter season, with resorts in the same region losing anywhere between 48-77 days.

Pidwirny says it will be a gradual decline, and in fact some resorts along Powder Highway might actually get better before they get worse.

“The ones near Banff, those ski resorts will do quite well, because the problem is January is too cold and people don’t show up,” he explained.

But that won’t last forever. Pidwirny predicts that by 2085 even places like Whitewater Ski Resort, located near Nelson, B.C., will see 60 per cent of their winter precipitation in the form of rain.

Douglas tells us that the changes are already starting to show.

“The things that we used to come to rely on, the knowns, are becoming strange. In the last decade we have seen several mountains in the coastal range just start to crumble, sections have just fallen off and that is a huge concern,” he said.

Lining up for the ski lift at Kimberley Alpine Resort. (Mia Gordon/The Weather Network)

Causes and solutions

The irony though is the resorts famous for their powder are also part of the threat that could destroy them. Emissions from the ski report industry include energy used to run chair lifts and gondolas, fossil fuel-hungry snow machines that are becoming more necessary as the climate changes, and then there are the skiers themselves. A report published in the Journal Mountain Research and Development says travelling accounts for 86 per cent of emissions from a ski holiday.

However, ski resorts and towns across B.C. and the world are starting to recognize they need to start making changes if they want to survive.

“Sustainability is really what the ski industry is looking at right now from a variety of different ways. A lot of resorts are looking at all kinds of ways to reduce their carbon footprint,” Mike McPhee, the board chair of Kootenay Rockies Tourism, told The Weather Network.

WATCH BELOW: Why this ski region is electrifying the 'Powder Highway'

Along the Powder Highway there are already a few examples. Revelstoke has introduced Sustain the Stoke, a sustainability program that hopes to reduce emissions in the town by encouraging green transportation.

The City of Fernie has started installing more electric vehicle charging stations. Kicking Horse has found it can reduce their emissions by slowing down its gondola on days with shorter lift lines.

And Kimberley turned an old mine into a solar panel facility that has the capabilities to power hundreds of homes.

WATCH BELOW: This former mining town is now powered by solar

For more coverage of the climate impacts and solutions along the Powder Highway, return to The Weather Network’s climate section over the coming weeks.

Thumbnail image: Skiers at Fernie Alpine Resort. (Destination BC)