Wonky weather gave us the smallest Antarctic ozone hole since the 1980s

The recovery of the ozone hole got a little boost this year from some unusually warm weather

The 2019 Antarctic ozone hole is the smallest on record since the 1980s, according to NASA.

Each year, as the Antarctic emerges from the darkness of winter, frigid polar stratospheric clouds are suddenly exposed to sunlight, setting off a flurry of chemical reactions.

The molecules that help form these clouds, called chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs), break down in the sunlight, and the resulting components eat away at the protective layer of ozone molecules high above the continent.

This process destroys ozone far faster than it is created naturally by sunlight, and it results in the Antarctic ozone hole.

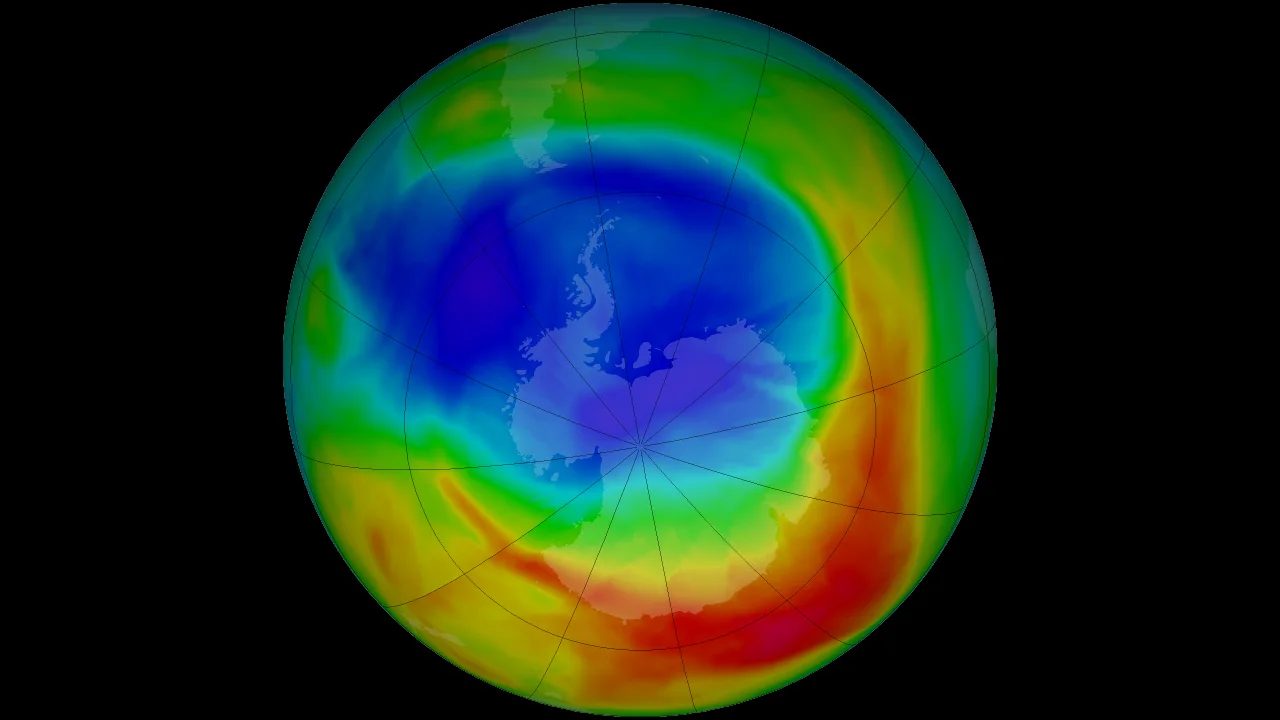

The average size and shape of the Antarctic ozone hole, so far in October 2019. Credit: NASA

Discovered in 1985, the Antarctic ozone hole forms each year between August to December. Growing to a peak size sometime in September, it then slowly closes up again in the following months, only to re-form the next year. Usually, depending on the weather, the size of the hole varies from year to year.

When scientists first discovered it, they found that the hole was growing at an alarming pace, due to the release of chlorofluorocarbons into the atmosphere. These chemicals were once widely used as accelerants in spray cans and as coolants in refrigerators and air conditioners. Moving quickly, the scientists gathered their evidence and went to the world's governments. Within two years, the 1987 Montreal Protocol had been signed, banning the production and use of CFCs.

Since then, careful yearly tracking of the ozone hole has revealed that our decisive action halted its growth by the late 1990s. While it took a few decades to see progress after that, NASA has seen a definite trend towards smaller and smaller ozone holes.

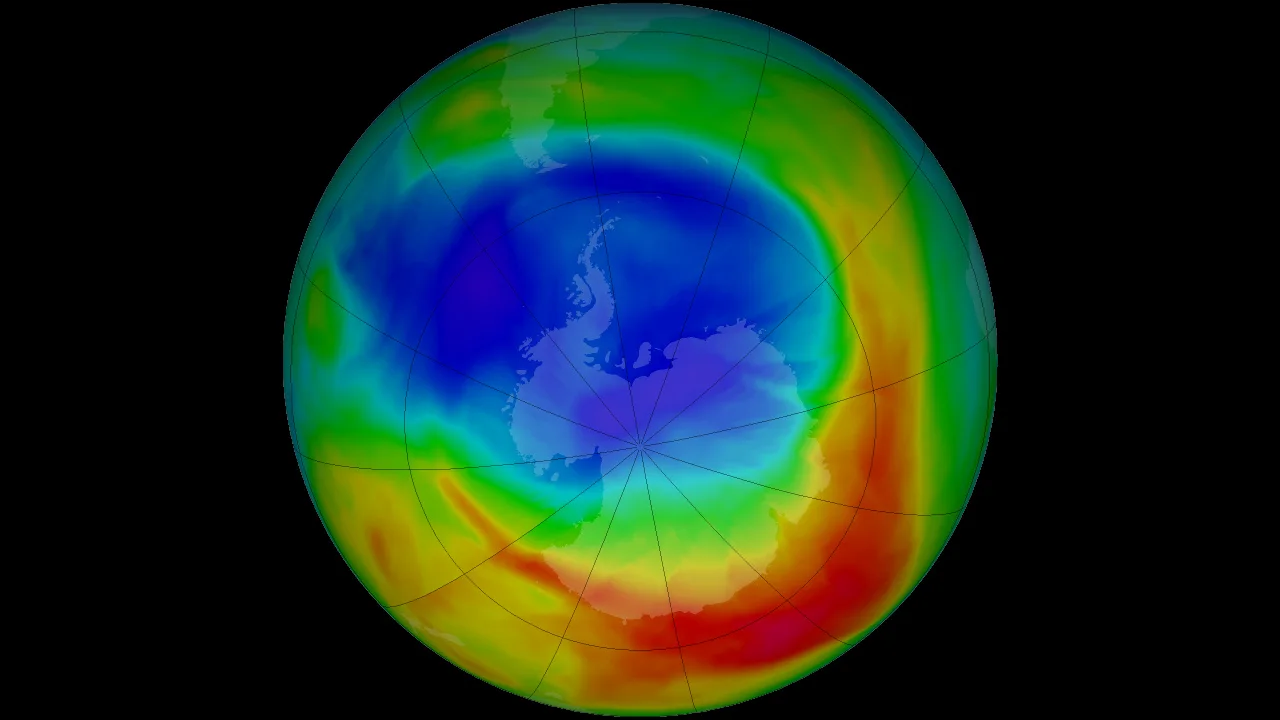

For 2019, the Antarctic ozone hole reached its largest extent of the year on September 8, at an area of 16.4 million square kilometres. In the weeks after, the hole then shrank significantly, to an average of around 10 million square kilometres.

So far, that is the smallest maximum extent we have ever seen from the ozone hole since its discovery, and the smallest ozone hole seen in September and October since the year 1982!

The maximum extent of the 2019 stratospheric ozone hole, on September 8, 2019. Credit: NASA

By comparison, the largest ozone hole ever recorded was on September 9, 2000, at 29.9 million sq km. The maximum extent of the ozone hole in 2018 was 24.8 million sq km, on September 20.

RARE WONKY WEATHER

This year's new record for smallest ozone hole is more encouraging news for the recovery of the ozone layer, but it isn't exactly normal.

According to NASA, the reason for the smaller ozone hole this year was an unusual pattern of warmer temperatures in the stratosphere. Temperature readings from the Antarctic stratosphere in September were the warmest they'd been in 40 years of record-keeping, at around 15°C above normal.

This warmth limited the formation of the frigid polar stratospheric clouds - where most of the ozone-destroying chemical reactions take place - and those clouds that did form did not last as long as usual.

At the same time, the warming also knocked the southern polar vortex off-kilter.

Similar to how warmer Arctic temperatures can slow the northern polar vortex, causing a wide swath of frigid air to extend down over North America, this same situation occurred in the south. A lobe of the southern polar vortex extended far north towards the southern tip of Argentina, while more ozone-rich air moved in behind to fill in the space over East Antarctica.

According to NASA, there's no link here to anthropogenic climate change, although this situation is highly unusual.

"It's a rare event that we're still trying to understand," said Susan Strahan, a NASA Goddard scientist from the Universities Space Research Association. "If the warming hadn't happened, we'd likely be looking at a much more typical ozone hole."

WHY DOES THIS MATTER?

Humans have a complicated relationship with ozone.

When we encounter ozone at ground level and breath it in, we considered it to be a pollutant. According to Environment and Climate Change Canada, exposure to ozone is linked to a variety of respiratory problems. It mainly results from industrial and car emissions, and it is one of the primary components of smog.

High up in the stratosphere, however, ozone is essential for our survival and the survival of most other forms of life on Earth. The ozone layer forms due to intense ultraviolet rays from the Sun striking oxygen molecules in the stratosphere, and splitting them apart. The resulting free oxygen atoms can then reform into another oxygen molecule, or they can join with an already existing oxygen molecule to form ozone.

Ozone formation in the stratosphere. Credit: Scott Sutherland

This process, along with direct absorption by the resulting ozone molecules, prevents the most energetic ultraviolet rays (UV-C) from reaching the ground. Ozone also absorbs the less intense forms of UV light (UV-B and UV-A), partially filtering them, so only a small amount reaches the ground.

This filtering of UV light is essential for our survival because, at those wavelengths, these forms of light are damaging or even lethal to life as we know it. We aren't just talking about sunburns here. These wavelengths of light can penetrate into our cells, doing direct damage to the genetic codes (DNA) that we require to live.

Without the ozone layer, complex forms of life would likely have never formed on Earth. The intense radiation from the Sun would have blasted them from existence.

A LESSON FOR CURRENT STRUGGLES?

This new low extent for the Antarctic ozone hole has no direct link to climate change. It does, however, stand as a good object lesson for taking meaningful action against climate change.

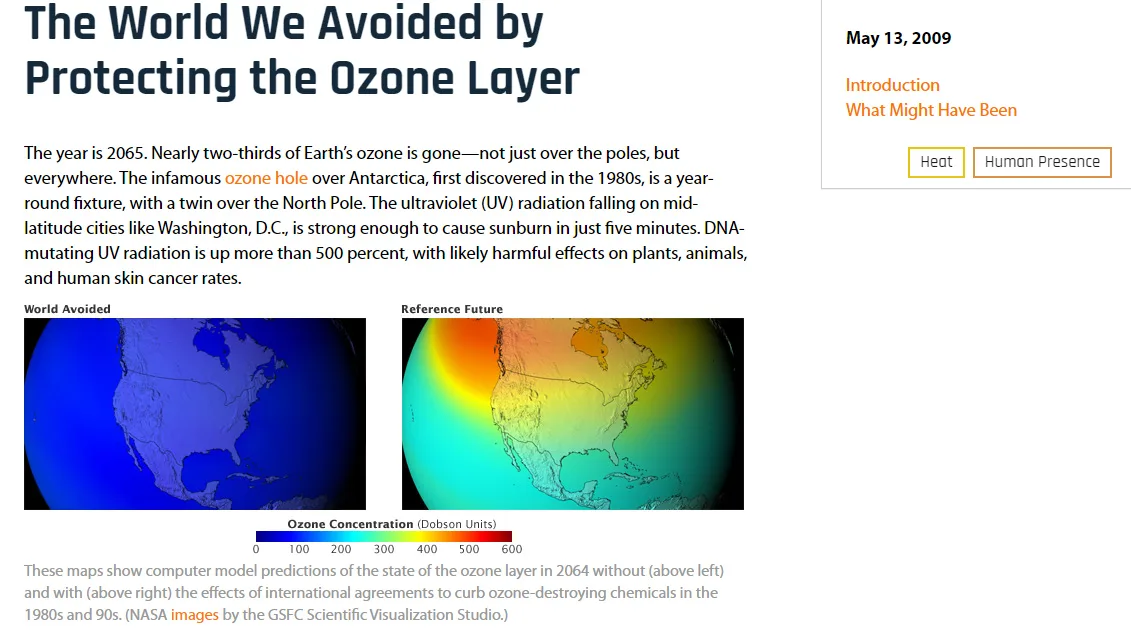

NASA's "The World We Avoided by Protecting the Ozone Layer" shows us a projection of what the world would be like if the Montreal Protocol had not been signed.

Even by now, in 2019 and 2020, the projection revealed alarming ozone losses. By 2065, stratospheric ozone levels would be so low that it would double ultraviolet radiation exposure at the ground, causing skin cancer rate to soar.

Check out the full story on NASA's Earth Observatory

"We simulated a world avoided," said Paul Newman of NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center, "and it's a world we should be glad we avoided."

Fortunately, because we faced the problem of ozone depletion head-on, we are seeing results.

Next year's maximum ozone hole extent will likely be up over 20 million square kilometres again, much like we saw in 2018. Still, this year is showing us that our global efforts to address the problem have succeeded, to the point where it only takes a bit of unusually favourable weather to effectively 'turn back the clock' on ozone loss to the 1980s.

Addressing climate change is a daunting task. By taking the same kind of action we did in 1987, however, we can tackle this problem and eventually see the same types of successes.

Sources: NASA | NASA Ozone Watch | ECCC | NASA Earth Observatory