Why beavers are a good ally in the fight against climate change

Once hunted and trapped to near extinction, the beaver — a national symbol of Canada — is having quite a moment among researchers for their ability to help prevent droughts, fires, and floods.

Pierre Bolduc connects a chain attached to a bunch of poplar trees with his quad before dragging them to the edge of the pond on his property.

The wood was free, a byproduct of forestry management in the thick woods surrounding his backcountry home near Bragg Creek, Alta., but it’s a much-welcomed gift for the furry “tenants” who have built a tiny home on his property.

“By tomorrow morning, all of these branches will be at the bottom of the pond next to the beaver lodge,” he told The Weather Network while pointing out to a large pile of sticks popping up in the middle of the water.

The trees were partially repayment to the beavers for some of the many benefits the rodent family has provided to his property over the years, a relationship that started after a call from a nearby farmer.

“They were going to shoot them. So it was either you move, you come to my place, and you're going to be loved and fed, or you're gonna get shot,” said the retired Canadian Forces pilot who had experience trapping wildlife from when he was a kid.

He thought they would be a perfect addition to the green journey he embarked on in 2010 after moving out to Alberta from Trenton, Ont. The beavers brought water — enough to form a massive pond that could serve as a perfect hockey rink in the winter for his two kids. But they also brought so much more.

Pierre Bolduc stands near the pond that was once a stream on his Alberta property. His goal is to be completely self-sustainable, which has led him to be one of the largest residential producers of solar energy in Canada. His next plan is to set up a micro-green operation in the hidden compartment of his garage, which he also uses to design art projects with a climate change message. (Rachel Maclean)

“I'm one of the lucky fellows in the valley here that still have a significant amount of water for my well. And … I've got to thank the beaver, because before the beaver showed up, I used to run out of water, which is a terrible thing.”

After using his homemade trap to bring the beavers to his land, he set up a solar-powered CD player that played sounds of a running stream by the small creek on his property. That enticed the beavers to get to work.

“This is the reason why the dam is so straight, it's because there was a line of speakers … there,” he said.

That raised the aquifer levels up by at least eight feet on his property, which also brought up the level on his well.

“So if you asked me if I love the beavers, oh, yes, I absolutely adore them. Because they helped me with my water issue,” said Bolduc.

The beavers even helped the local municipality, as they no longer have to come and clear out some of the culverts nearby.

Raising the water level also helps when it comes to wildfires, given the pond has created a lush environment more resistant to flames. Bolduc has a fire hose nearby so he can use the pond water to battle any fires that spring up, given his property is roughly 50 minutes away from the nearest fire hall.

While Bolduc has come to his own conclusions on what he calls an “incredible species of nature,” it turns out that new research supports his findings.

The science of beavers

“One of my big discoveries is that beaver complexes are unique in that they are almost entirely able to withstand the effects of drought, which then helps them withstand the effects of wildfire,” Emily Fairfax, an assistant professor of environmental science and resource management at California State University Channel Islands, told The Weather Network.

Her work is part of many studies released this past year on the benefits of having the lowly beaver be part of resilience projects in the era of climate change. They have also been found to help reduce flooding, and cool temperatures in headwater streams.

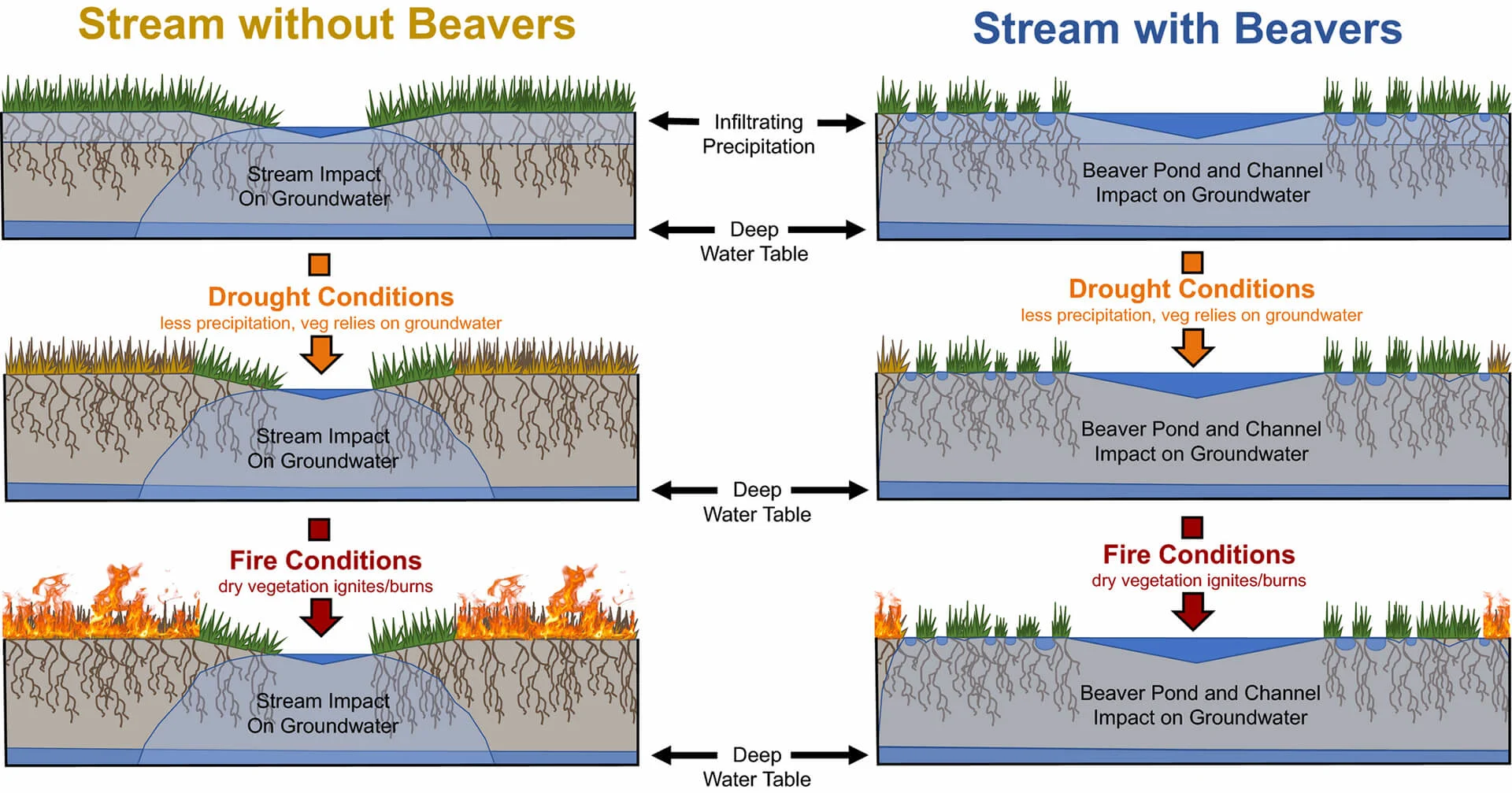

“So when you have a really dry period, and everything starts to sort of shrivel up and wilt, these beaver complexes have stored so much water that the plants stay absolutely green and lush,” Fairfax explained.

“And then if you have some sort of an ignition in the landscape, like a lightning strike or a campfire that didn't get put out, or powerline, regardless of what it is, those really wet green patches are harder to burn. It's like if you try to go out and start a campfire, you're not gonna to go gather the wettest leaves you can find, you're gonna gather dry stuff. And these beaver ponds, they're quite wet, and so they're quite hard to burn.”

She says it's all one big interconnected cycle of processes when it comes to beavers and climate change.

“So whenever you have a beaver build a dam, that starts to slow down the water, and that gives the water time to seep out into the soil around it, grow a bunch of vegetation, and then keep that vegetation healthy during droughts and fires,” said Fairfax.

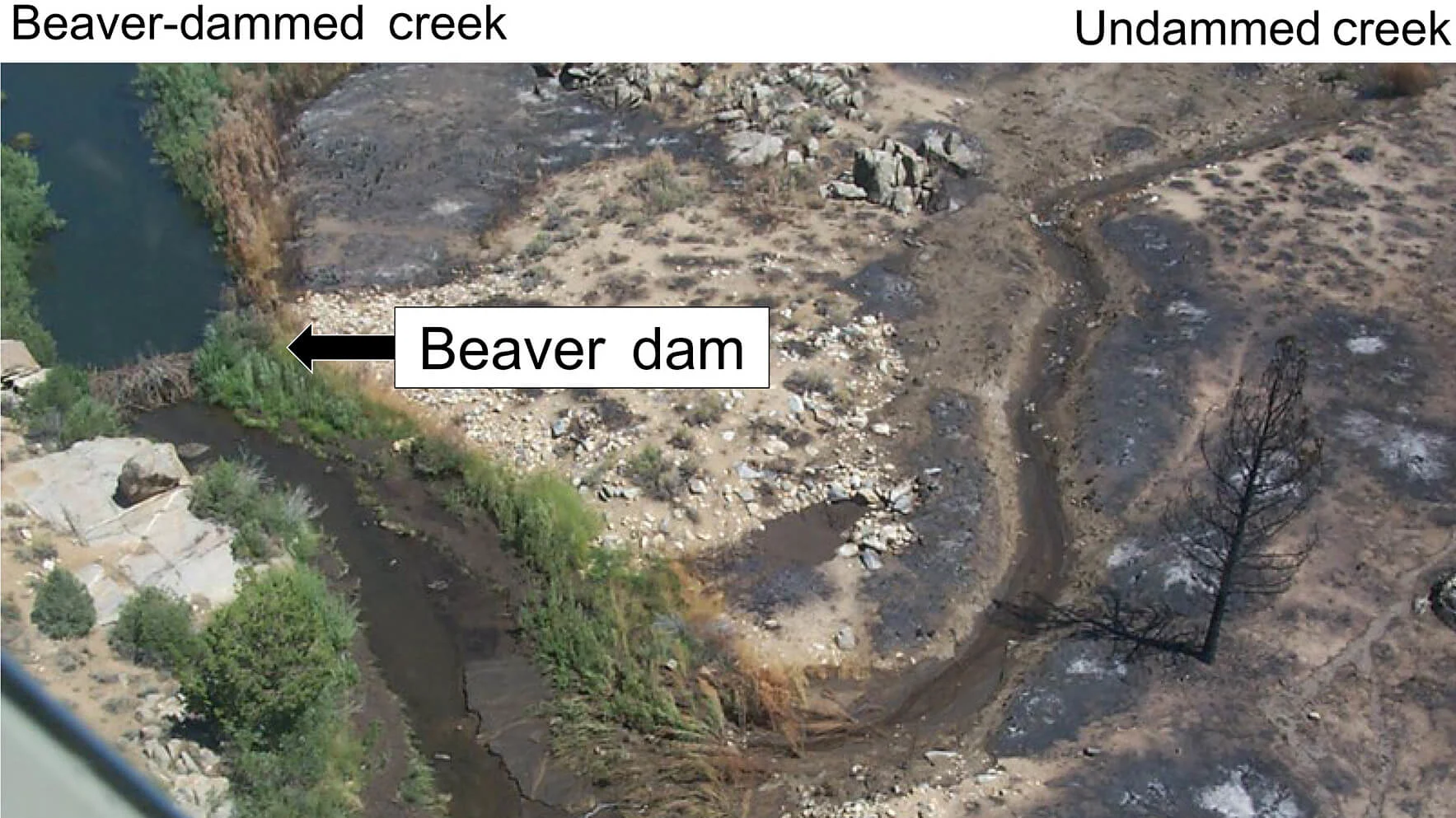

The beaver dam located on the left in the above photo helped stem the damage from a wildfire in California. (esajournals.onlinelibrary.wiley.com)

“Now, if you have floods, it can also help attenuate that flood wave and sort of take the power out of it, spread it out in the landscape, so that downstream it's a little bit less erosive. And all of this put together, really, it's just very complex hydrologically,” she added.

While it may look a little messy, that messiness helps make rivers and streams be resilient to all sorts of disturbances — even helping to restore them. For example, after a wildfire, a lot of the hillslopes have been burnt pretty intensely, and there’s ash and sediment washing into the streams.

Conceptual model of vegetation response to normal conditions (top), drought (middle), and fire (bottom) in creeks with (right) and without (left) beavers. (esajournals.onlinelibrary.wiley.com)

“When they hit that beaver pond, the water is so slow that a lot of that ash and sediment just settles out and actually helps build it back up and reconnect it to its floodplain even faster. And the downstream water is clear and it's cleaner and the beaver pond, it's fine. It just settles it out and makes it part of the mud,” said Fairfax.

Storing all of that water can cool as well. During hot summers, beaver dams provide deep pools that can mix in with some shallower “runs and riffles.”

“In those deep pools you have these thermal refugia, or basically cold patches, that fish can go hang out in — and especially those fish that have a really narrow band of temperatures they're OK with — and just wait out the hottest days of the year,” said Fairfax.

“The dam also sort of pushes the water into the ground where it can mix with groundwater and groundwater is very shaded from the sun. The sun doesn't beat into the Earth and get it. So it's quite cold often. And we have that surface water, which is a little bit warmer, mixing with that groundwater, which is a little bit cooler, the water that comes back up and joins the stream later is overall a little bit cooler.”

How to bring back beavers

The largest rodent in North America, beavers are often seen as pests to be destroyed — something that is completely legal in provinces like Alberta on private property or with a damage control license on public lands. Some farmers, and even cities like Calgary, have historically trapped them when they set up shop in unwanted areas.

“I think it’s a little hard to imagine what the continent would look like if it was fully re-beavered, and they were back to their historic numbers. There were anywhere from 100-400 million beavers across North America before the fur trade and colonization. And afterwards, we're down to like 10-30 million, so 10 per cent of the historic population,” said Fairfax.

Emily Fairfax operates a drone while conducting some field research on one of her many trips to observe beavers in their natural habitat. She says if beavers can bring a little hope with all the doom and gloom that climate change brings, they are certainly climate heroes in her book. (Submitted by Emily Fairfax)

“And if you see these beaver complexes just sort of sprawling around the landscape. And you're like, ‘Wow, this is huge.’ Imagine that times 10. It's not just like, ‘Oh, a small stream has been changed.’ It's truly the watershed that has been changed.”

She says there are a few ways to bring beavers back so there is less conflict with humans, including creating a good habitat for where you want them to build.

“If you have beavers in really high conflict areas and all coexistence has failed, like wrapping the trees and fences failed and putting in pond levellers has failed, you can take that beaver and in many places you can relocate it to somewhere where it's more desired — where it's going to have a better chance to live,” said Fairfax.

“Relocation is definitely not a guarantee. But if that beaver was sort of doomed to be lethally managed anyways, you might as well try to let it establish itself in a watershed where it's further away from human conflict.”

Bolduc agrees.

“They do magic,” he said. “We need them to ease the stress that we are putting on the ecosystem by maintaining a … friendly relationship with the beaver.”

Thumbnail image: A beaver snacks on a stick near its home along a riverbank in Calgary. (Kyle Brittain)

With files from The Weather Network’s Kyle Brittain