Peatlands create safe, natural havens from wildfires — but they need protection

Peatlands act as and even foster refugia — locations that play a vital role in plant and animal species surviving disastrous wildfires and then resettling their native habitats. But, in fire-wracked Alberta, the province needs to take a proactive approach to protect peatlands to see these benefits.

As Alberta’ faces down a fiery future under climate change, some parcels of land are going to become increasingly important.

Called climate refugia, these spots are buffered against climate change thanks to different factors like proximity to water, among many others. They also act as safe havens where plants, animals, and other forms of life can weather the worst effects of climate change, such as the wildfires Alberta is seeing this year.

New research shows that, at least in Alberta’s northern boreal forests, peatlands can help foster refugia during wildfires. The authors note this is another way peatlands are particularly important to the climate of the future. Alberta’s 92,000 square kilometres of the waterlogged land also stores 19.9 billion tonnes of carbon. This carbon is at risk of being released into the atmosphere as humans disturb peatlands through fossil fuel and mineral extraction, and as climate change disrupts them.

“Potentially, these can be looked at as areas of refuge for, say … plants that are native to the area that can then go on and reseed those burned areas,” Christine Kuntzemann, a climate change analyst with the Canadian Forest Service (CFS) and author on the paper, told The Weather Network. “They're also important because they're kind of like a safe haven for wildlife, both in the immediate time frame, and then going forward into the future as well.”

Moisture mapping

In the research, Kuntzemann and her colleagues looked at satellite data for Alberta’s heavily forested north between 1985 and 2018. They took yearly data on how much surface area was burned from the Canadian National Fire Database, and data on the severity of the burns from their colleagues’ previous work. They also added other factors in — such as yearly variations in temperature, and soil moisture and vegetation type in different parts of the region — from various sources such as the Alberta Biodiversity Monitoring Institute.

The team input this data into a statistical model that, functionally, gave them a kind of map of northern Alberta showing how likely a given plot of land would be a refugia for flora and fauna. For the sake of the research, wildfire refugia were considered parcels of land that appeared to be either relatively untouched by fires.

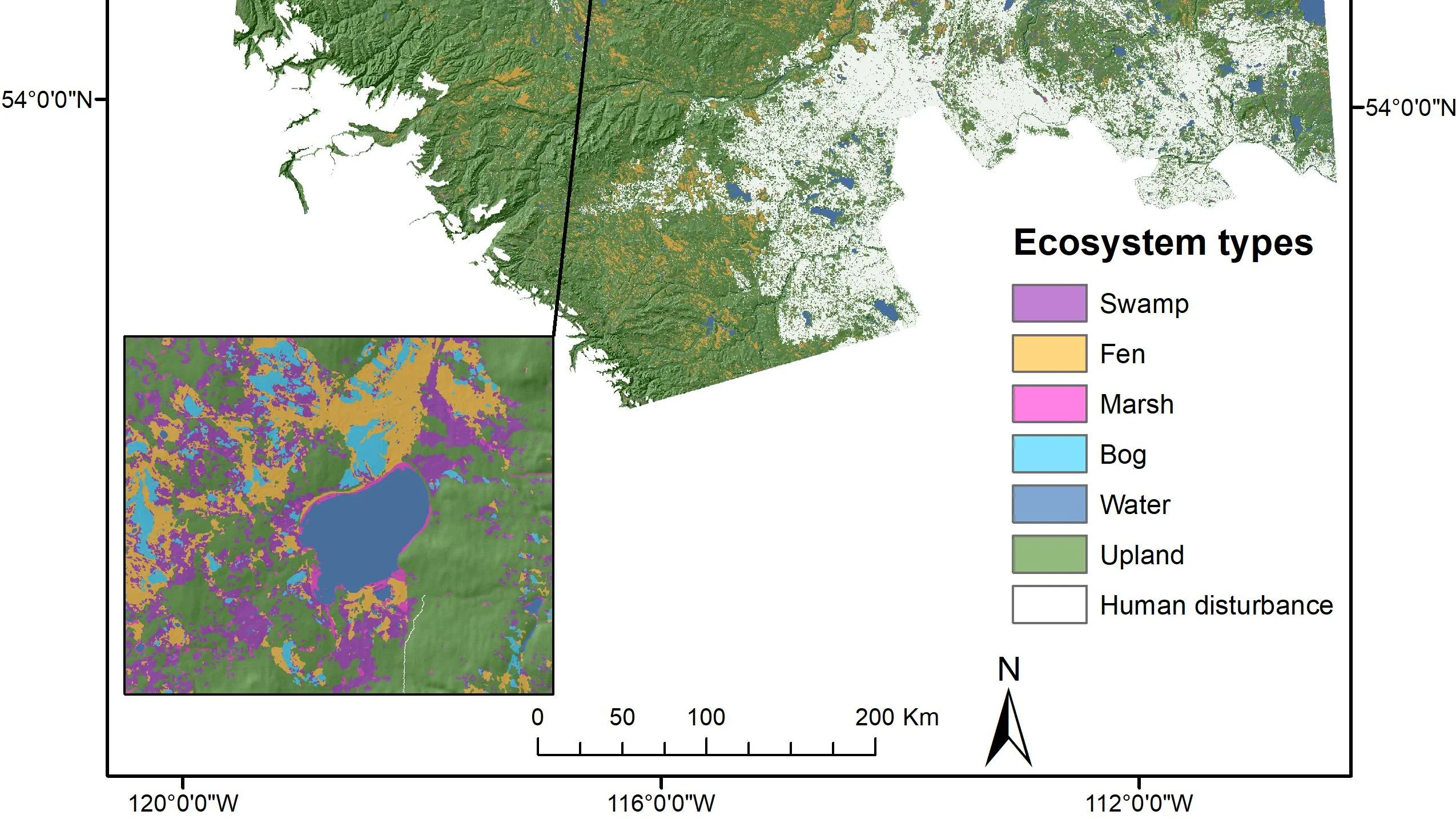

Location of uplands and wetlands in part of Alberta's boreal region, seen in a recent paper on how peatlands foster climate refugia in the province's northern forests. (Supplied by Christine Kuntzemann)

In general, peatlands appeared to be likely wildfire refugia that can withstand wildfires, with forested fens — a kind of peatland that is often fed by a stream or river — being 64 per cent more likely than upland forested regions to go relatively unburnt. Places near peatlands also had good odds. Forested areas had up to a six-fold increase in likelihood of being refugia when there were more bogs nearby (bogs are like fens but get their moisture from accumulated rainwater).

According to Kuntzemann, peatlands keep wildfires at bay in a few different ways. On average, they have more moist plant matter than other habitats like forests. Additionally, water from some types of peatland can leach out into areas nearby, making them less flammable.

But Diana Stralberg, a research scientist with the CFS and one of the paper’s coauthors, said not much is known about how peatlands buffer nearby areas. It’s a “bit of an open question,” she told The Weather Network, adding that factors like particularly dry or hot years can diminish the effect.

“They can be overwhelmed by fire, [or] extreme fire weather,” she said, adding her team plans to do more research into how peatlands protect neighbouring areas.

Kuntzemann noted it’s hard to apply her study’s findings to other regions. For example, Ontario’s forests are expected to grow wetter, rather than drier, she said, so the scenario would likely play out differently.

An aerial view of burned aspen trees near Fort McMurray, Alta. (Supplied by Ellen Whitman)

Protecting peat

However, peatlands in Alberta aren’t being adequately protected, according to Phillip Meintzer, a conservation specialist with the Alberta Wilderness Association. The provincial government established the Alberta Wetland Policy in 2013, but it places a large emphasis on offsetting the damage done by human activities on wetlands, and still allows for industry to use and damage the areas.

This poses a problem as peatlands form due to the accumulation of dead plant matter over thousands of years, so offsetting that isn’t a simple or easy process. He argues that the provincial government needs to create new policies that protect peatlands from development.

“Overall, we don’t do a great job,” Meintzer told The Weather Network.

According to Kuntzemann, the added benefit of fostering refugia during wildfires highlights the importance of protecting peatlands. She believes the province should ramp up its efforts.

“The more we find out about peatlands, the more important we're finding them in a lot of different respects," she said. “They're also really important carbon stores. And so the more you disturb that hydrology, the less capable they are functioning at their best level.”

Thumbnail image: Alberta peatland is seen singed in 2015. (Supplied by Ellen Whitman)