Ancient marine extinctions reveal dangers of current ocean acidification

How an ancient asteroid impact affected our oceans is highlighting the dangerous path we are on due to carbon emissions

Sixty-six million years ago, a massive asteroid smashed into the Gulf of Mexico, touching off a global extinction event. Scientists estimate that up to 75 per cent of all species on Earth quickly died out following this impact, including all species of non-avian dinosaur.

A new study, led by Michael Henehan at the GFZ German Research Centre for Geosciences, shows how the acidification of the oceans that followed the Chicxulub impact played a large part in this die-off.

This discovery provides insights into exactly what caused this mass extinction event. Previous research has suggested that there was a gradual degradation of Earth's ecosystems and gradual acidification of ocean waters due to extensive volcanic activity leading up to the impact. This new study, on the other hand, shows that rapid ocean acidification only occurred directly after the meteorite strike.

This painting by Donald E. Davis depicts the Chicxulub asteroid slamming into shallow waters near the sulphur-rich Yucatan Peninsula, in what is today southeast Mexico. Credit: NASA

"For years, people suggested there would have been a decrease in ocean pH because the meteor impact hit sulphur-rich rocks and caused the raining-out of sulphuric acid, but until now, no one had any direct evidence to show this happened," Henehan said in a Yale University press release.

Henehan and an international team of researchers found this evidence by looking for tiny plankton fossils in sediments laid down before and after the impact -- in cores drilled from the ocean floors and from rocks formed at the time. The type of plankton they were looking for, known as foraminifera, are known to grow calcium-carbonate shells, which makes them very sensitive to ocean acidity levels.

Heterohelix globulosa, a species of foraminifera sampled from K-Pg boundary clays in Geulhemmerberg Cave, shown under a microscope. Credit: M. Henehan, et al/PNAS

When ocean waters have a higher pH level (more basic), growing these shells is easy. When pH levels drop (become more acidic), their shells are thinner or even non-existent.

One site they collected samples from, Geulhemmerberg Cave in The Netherlands, was found to have sediments that were laid down during the 100-1000 years directly following the Chicxulub impact. In samples from these layers, they discovered a change in the number of foraminifera fossils that suggests a period of rapid ocean acidification that lowered ocean pH levels by around 0.25, or more, during that time period.

In Geulhemmerberg Cave, in The Netherlands, the Cretaceous-Palaeogene boundary (K-Pg boundary), which marks the Chicxulub impact event, is clearly visible as a grey, clay-rich layer, sandwiched between yellowish carbonate sediments. Credit: M. Henehan

"The ocean acidification we observe could easily have been the trigger for mass extinction in the marine realm," Pincelli Hull, a senior author of the study from Yale University, said in a statement.

With the die-off of these tiny creatures at the base of the food chain, this contributed to the mass extinction of ocean life farther up the food chain.

A WARNING FROM THE PAST?

With rapid ocean acidification linked to the mass extinction of life on Earth comes a stark warning about what could happen to the planet now, if we do not quickly end our dependence on fossil fuels.

For reference, pure, distilled water has a pH of 7.0, while in pre-industrial times, ocean water had a pH level of around 8.1.

Since the widespread burning of fossil fuels began in the mid-1800s, the oceans have been absorbing more and more carbon dioxide, and now take up at least a quarter of all carbon dioxide from fossil fuel emissions.

Since carbon dioxide dissolved into ocean water produces carbonic acid, this has resulted in a lowering of ocean pH levels to around 8.0. Much of that acidification has taken place in just the past 70 years.

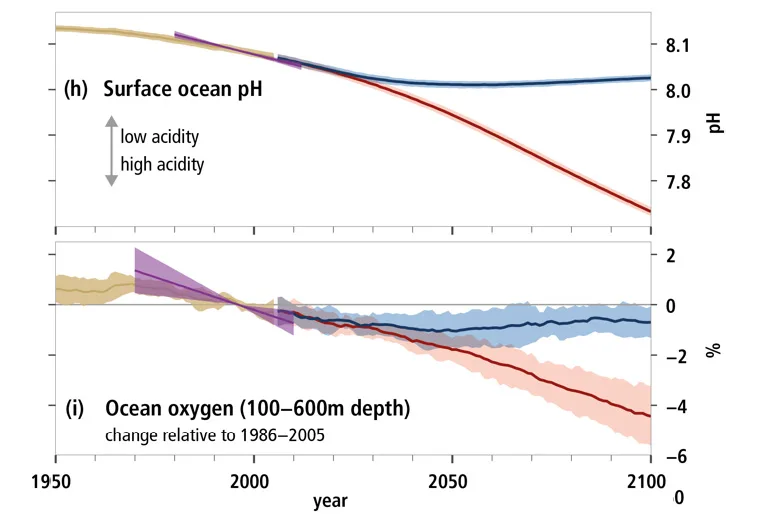

Ocean pH levels and dissolved oxygen concentrations, as measured up to 2012, and as projected by ocean models to the year 2100. Credit: UN IPCC

According to the latest IPCC special report The Ocean and Cryosphere in a Changing Climate, if we continue to emit greenhouse gases at an increasing rate, ocean pH levels are expected to drop further, reaching around 7.75 by the end of this century. That represents a total drop in pH of 0.35 since pre-industrial times.

"If 0.25 was enough to precipitate a mass extinction, we should be worried," Henehan said, according to a report by The Guardian.

While ocean and atmospheric conditions were different during the time of the Chicxulub impact, it is the overall magnitude of the changes, over such a short amount of time, that is most important.

Life can adapt to many adverse conditions if given sufficient time. It is the rapid time frame that these changes are taking place over that makes them so worrying.

If a change in ocean pH of 0.25 over a few hundred to a few thousand years following the Chicxulub impact caused such a dramatic die-off of marine life, the projected ocean acidification we could see by 2100 could lead to a similar mass extinction.

Sources: PNAS | GFZ-Potsdam | Yale University | The Guardian