Five unexpected ways climate change will impact your health

Healthcare providers and scientists are going to have their hands full trying to keep ahead of these intensifying threats.

Climate change keeps marching along, and Canada is right in its crosshairs.

A 2019 study found Canada is warming twice as fast as the global average, and with that warming will come more frequent, and more intense, severe weather events.

It's not hard to imagine the effect that will have on infrastructure or the economy, but one thing that needs to be considered as well: How will a warmer world impact Canadians' health?

Here are five things to prepare for in the coming decades.

DISEASE-CARRYING SPECIES WILL THRIVE

The prospect of warmer and longer summers sound like paradise for a famously winter-weary nation, but the higher temperatures will have many a sting in the tail -- or, rather, a bite.

Specifically, they'll make more of Canada's territory suitable for particular kinds of disease-carrying organisms, like ticks and mosquitoes.

Western black-legged tick (Ixodes pacificus). Source: Wikimedia Commons

Take Lyme disease, for example. If you don't remember seeing annual public health warning blitzes about the disease when you were growing up, along with the black-legged ticks that can transmit it to humans, that's because they have become more common in recent years, with measurable consequences.

In Ontario, for example, the number of 'probable and confirmed' Lyme disease cases reached 959 in 2017, three times the annual average of the past five years. The number of cases in the Ottawa area in 2017 was double that of 2016.

That's according to the October 2018 issue of the Canada Communicable Disease Report, which noted the geographic range of the ticks has been gradually expanding, reaching even into northern Ontario, and the researchers say that expansion is set to continue as the climate warms.

Other carrier species, such as mosquitoes, will also thrive, and with them threats such as West Nile, which researchers warn may appear more often. Canadian mosquitoes may also become infected with new diseases as-yet unobserved locally in Canada, and spread to new regions, while mosquito species not native to Canada may find our future climate more habitable as well.

Aside from the carriers, researchers say the way they'll spread their pathogens will change, as warmer climates influence their life cycle. Egg development time will shorten for some species, as will the incubation period within a given disease-carrying insect, for example.

"Furthermore, as the winters become shorter and summers become longer, the duration of climatic suitability for disease transmission will increase," Public Health Agency of Canada researchers wrote in April 2019.

FOOD-BORNE DISEASES WILL MULTIPLY

Safety standards and regular inspections have combined to make Canada's meals as safe to eat as ever, but no system is perfect, and even with all these safeguards, food-borne illnesses still happen.

Canadian government figures estimate, on average, some 4 million Canadians are affected by food-borne diseases yearly, resulting in 11,600 hospitalizations and 238 deaths, caused by around 30 distinct viruses, bacteria and parasites. And food scientists are starting to take a serious look into how that mix will vary as the climate continues to warm.

"The prevalence of these diseases is modified by climate change through alterations in the abundance, growth, range and survival of many pathogens, as well as through alterations in human behaviours and in transmission factors such as wildlife vectors," reads a paper published in April's Canada Communicable Disease Report.

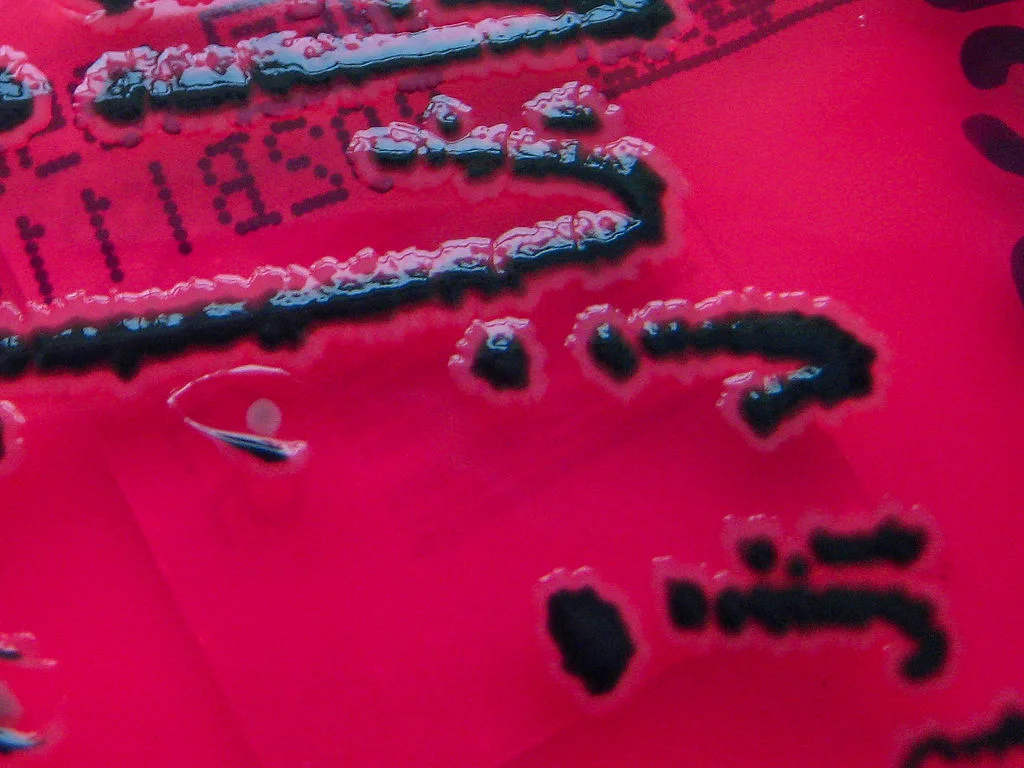

Salmonella species growing on X.L.D. agar. Nathan Reading/Wikimedia Commons

That paper contains a full-court press of factors influencing the number of food-borne disease cases in the Canada of the future.

Longer summer seasons mean more barbecues and picnics, and more opportunities to come into contact with mishandled or contaminated food. A longer growing season likely means people may eat more fresh produce, which can be more easily contaminated. Produce fields are frequented by all kinds of wildlife, which will roam more widely, bringing disease-carrying bacteria or parasites with them, for longer parts of the year. Warmer oceans mean more risk of contamination of shellfish from phytoplankton and zooplankton blooms.

If you've the stomach for it, we do recommend taking a look at that report. The researchers assessed 11 kinds of bacteria known to be the source of food-borne illnesses, and of the five that make up 90 per cent of cases in Canada, four were found to be influenced by at least some of the coming climate changes.

The most abundant and impactful, norovirus, can be affected by heavy rains and flooding, and lower air temperatures. Salmonella, meanwhile, is influenced by changes in the seasons' length and timing, as well as extreme weather and increased temperatures.

Health researchers are also keeping an eye on other threats that are currently not common. Increased humidity, for example, encourages the growth of fungi, some of which grow on crops and can be the source of harmful mycotoxins.

ALLERGY-SUFFERERS MAY BE IN FOR A WORSE TIME

Image: Getty

Allergy sufferers know navigating their annual pollen bout can be a pain, and in a warming world, there's a lot they won't like about the season.

The Public Health Agency of Canada says climate change will likely mean higher allergen counts, due to increased pollen production in plants from warmer weather and milder winters. Higher CO2 levels, the biggest driver of global warming, can also be a boon for pollen-producing plants.

We asked researchers at Aerobiology Research Laboratories in Ottawa for a more detailed look at how future allergy seasons can play out, and while there are a lot of variables, Aerobiology's director of operations and quality management, Dawn Jurgens, says the most probable change is that pollen seasons will start earlier than we've come to consider normal.

"However, that does vary and is not always consistent," Jurgens adds as a caveat. "Ragweed could have the opposite effect as warmer weather could delay its pollen production, as ragweed thrives in cooler temperatures such as what we typically see in September, which is generally the peak of the season."

But ragweed allergy sufferers should be prepared for an unwelcome flip side, Jurgens says.

"We are starting to see ragweed in areas where we have not typically seen them in the past, and we highly doubt this is due to urban planning where they are purposely planting ragweed," Jurgens says. "With climate change it is quite possible that the changes are creating environments that promote ragweed growth."

Image: Getty

As for how long Canada's future allergy seasons could last, Jurgens says that depends on the pollen source. Grasses and weeds will have a longer growing season in a warmer world, and thus a longer allergy season. Trees, however, are another story: They typically produce pollen in the cooler temperatures of springtime, so warmer or shorter springs could nip tree pollen season in the bud.

That's great for allergy sufferers, but not so much for the environment: Trees absorb CO2, and Jurgens says limited forest growth derives us of a key ally in the fight against future climate change.

EXTREME HEAT EVENTS COULD BECOME MORE DEADLY

Consistently warmer climates will have numerous knock-on effects from the environment to the economy, but hotter temperatures alone pose their own health risks.

A recent climate change report released by the Canadian government found that Canada has been warming twice as fast as the rest of the world, and more warming is ahead. Depending on how governments respond to the crisis, the best-case scenario for warming is 1.8°C in a low-emissions scenario, and as high as 6.3°C if emissions continue unchecked.

2X FASTER: CANADA'S WEATHER FUTURE IN A CHANGING CLIMATE

Over the course of a given year, any climate has its temperature ups and downs, but in a warmer-than-average Canada, both the ups and the downs are expected to become more extreme.

"For example, the annual highest daily temperature that currently occurs once every 20 years, on average, will become a once in 5-year event by mid-century under a low emission scenario (a four-fold increase in frequency) and a once in 2-year event by mid-century under a high emission scenario (a ten-fold increase in frequency)," the report suggests.

The extremes will also become more frequent. An Environment Canada survey of eight Canadian cities' projected climate in the coming century found a substantial increase in the number of days with high temperatures over 30°C -- typically temperate Victoria, B.C., goes from an annual average of one 30-degree day in 1961-1990, to 11 by century's end. At the other extreme, already sweltering Windsor's annual number of days above 30°C jumps from 19 to 72 by day's end -- a fifth of the year, and most of the summer.

Health authorities are already preparing for these kinds of heatwaves, with plans ranging from alerting and communication to identifying vulnerable groups to target for protection.

WATCH BELOW: HEAT WAVE 'SURVIVOR KIT': ESSENTIAL PACKING DURING HEAT WARNINGS

Certainly, the consequences of extreme heat are dire. A recent report into the aftermath of 2018's heatwaves in Quebec attributed almost 93 deaths to the extreme temperatures, many of them seniors over 60 and other vulnerable people. In 2003, a heatwave in Europe killed tens of thousands of people.

CLIMATE CHANGE WILL HURT PEOPLE'S MENTAL HEALTH

Everybody expects severe weather every now and then, but what happens when the hits keep coming, season after season, and much harder than you're used to?

Scientists have started looking into the effect that has on people's mental health, and the results aren't encouraging.

For starters, there's the impact of simply having to deal with particular extreme events such as wildfires and flooding, both of which are expected to worsen as the world warms. Writing in the B.C. Medical Journal earlier in 2019, physician Dr. Elizabeth Wiley wrote that the impacts of climate change have begun to be associated with "numerous" mental health conditions, such as "post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), depression, anxiety, grief, substance use disorders, and suicidal ideation among many others." More vulnerable parts of society, such as children, the elderly, and people with pre-existing conditions, are especially at risk, Wiley says.

The effects of the 2016 Fort McMurray fire, which forced more than 80,000 people to flee their homes, provide a snapshot of what Canadians affected by extreme weather can expect. One researcher, Dr. Peter Silverstone of the University of Alberta, specifically looked at younger people who were part of that exodus.

"The 2,800 young people [had] much higher rates of depression, much higher rates of PTSD and the really worrying thing is that we did our first analysis 18 months after the wildfire," he told CBC's Cross Country Checkup. "We've just followed up two-and-a-half years after the wildfire and very little improvement. So these are long term impacts. And you have to recognize they're going occur."

WATCH BELOW: PSYCHOLOGIST CLAIMS INCREASE IN MENTAL HEALTH CASES DUE TO B.C. WILDFIRES

Even for those who emerge from a particular crisis more or less unscathed, there are other, longer-term effects of that crisis that linger long after.

"Suddenly you have issues with your house, you have issues with insurance, you have issues with various other things, your life has changed," Silverstone told CBC.

Even for people who may not be directly affected by a particular disaster, the ever-present spectre of climate change has its own impact on people's mindset -- something Dr. Courtney Howard, lead author of the Lancet Countdown report released in late 2018, calls 'ecological grief.'

Howard told the Ottawa Citizen that that kind of anxiety even has a specific word: 'solastalgia,' which she describes as “feeling homesick when you are at home,” and also "related to an Inuit word that refers to a friend behaving in an unfamiliar way."

The research also found that that anxiety could also come from feelings of helplessness as climate change progresses -- but, conversely, that anxiety can be soothed by governments taking concrete steps to combat climate change.