How Kanaka Bar is creating a path forward following climate catastrophe

After surviving a deadly heat wave and devastating fire, food security and renewable energy is more important than ever for the First Nation located just 18 kilometres south of Lytton, B.C.

The Kanaka Bar Indian Band in B.C.’s Fraser River Canyon is known as one of the hottest places in Canada. It was also ground zero for the country’s deadliest weather event in Canada to date.

There were 619 heat-related deaths during the heat dome that hit Western Canada in late June 2021. The entire town of Lytton, B.C., subsequently burned in a wildfire. Unlike its neighbours, Kanaka Bar was spared from the raging fire but every community in the region was deeply impacted. Residents moved away, businesses closed, and the painful rebuilding process is still underway two years later.

Melina Laboucan-Massimo, one of Canada’s leading climate change advocates and the host of Power to the People, visited the nation in 2018 before the tragedy struck to see how it was already building climate mitigation strategies, renewable energy, and food independence to protect Kanaka Bar from exactly what took place a few years later. In advance of publishing this latest episode on our platforms, The Weather Network connected with former chief Patrick Mitchell for an update on the rebuilding underway.

Watch past episodes of Power to the People here

“We had incredibly traumatic events that impacted our community and it compounded because we had the heat, we had the fire, then we had the atmospheric river, and then we had the snow and freeze,” Michell, who retired in July 2022, said in an interview this spring.

“We can't control the weather, but we can mitigate its impacts.”

An aeriel view of the wildfire damage in Lytton, B.C. (CBC)

His house on the nearby Lytton First Nation, where his wife is from, burnt to the ground from radiant heat. Now he is lending his expertise on renewable energy and fireproof materials as the rebuilding process continues, but costs have been an issue.

An investigation and class action lawsuit regarding the cause of the fire is still underway, with some pointing to sparks from nearby rail lines. The lengthy process, which some are hoping will help with rebuilding costs, could end up at the Supreme Court.

Michell says new infrastructure must be built to withstand heat, but he’s already seen that’s not always the case — such as wooden power poles being erected again instead of the more costly route of underground electrical distribution that helps protect communities from future power outages. He hopes sustainability will be the focus at a rebuilding meeting planned for May, but he’s also concerned conditions could be ripe for another tragedy.

WATCH MORE: Looking back at Lytton's devastating wildfire one year later

“They've already had 14 forest fires … in the last 10 days,” said Michell this March, adding nearby communities need to clear out thick brush and create fire breaks like his ancestors have done for thousands of years.

There is no shortage of fuel for wildfires near Kanaka Bar, but the former chief says there are ways to responsible manage it. (Power to the People)

The standard Indigenous land management practice of controlled burns, which inspired many FireSmart programs, can significantly reduce out-of-control forest fires. If they don’t, he can see another worst-case scenario — something he inadvertently prophesied during the filming of Power to the People years before disaster struck.

“By taking down the dead, diseased, and dying, and thinning the trees, we've created a scenario where we'll have a ground fire of this forest fire. But just a little further down, you will see how brushy and dense it is. That would cause a raging forest fire that was indefensible and cause risk to life,” the former chief told Laboucan-Massimo in the episode, which can be viewed above.

Tale of two communities

Michell said not one First Nation person died during the heat-induced crisis, but sadly two lives were lost by the fast spreading fire in Lytton. The village also ran out of water.

Prior to the fire, Kanaka Bar did climate risk assessments to understand its potential vulnerability of its water use and decided to make a plan for the next 100 years that focuses on ecosystem health, drinking and irrigation, fire protection, and energy production — enough for the entire region in case they get cut off again from the outside world.

In 1990, Kanaka Bar put in an application for the Kwoiek Hydro Project that required a community filing of a water license application. During the 10 years following, their baseline data collections demonstrated a significant change in their traditional territory’s ecosystems.

Kanaka Bar is building climate resiliency in the face of extreme heat. (Power to the People)

The community raised concerns around their project having adverse cumulative effects and exacerbating climate change during the EAO review in 2000 and 2006. Following the construction of the project in 2011, they codified their traditional laws and processes creating a Land Use Plan in 2015 and completed a Climate Change Assessment and Transition Plan in 2016. Kanaka Bar has been implementing a Climate Resiliency Plan since 2021, and will update their plans in 2024.

READ MORE: How Tlingit Nation harnesses hydropower, geothermal energy

The community’s proactive responses is also why Kanaka Bar has put so much time into creating sustainable food and energy sources that won’t be affected by a future crisis. For example, grocery stores shut down in the wake of the fires. Instead the nation has a “take only what you need” approach to community food sources, with a deer farm and closed-loop aquafarm expected to come online in addition to the food forest and chicken raising already underway.

It comes at a time when salmon populations are also under immense stress.

“Sockeye salmon, their spawning temperatures are 18 C,” Michell told Laboucan-Massimo in the episode. “It is the first week in August and the Fraser River is already in excess of 20 C.”

Known as the “people of the salmon,” Michell says it’s taking a lot more effort for less fish so sustainability is key, which also goes for energy production. Kanaka Bar is growing its solar and battery storage capacity, which creates revenue that can be reinvested into the community.

A band member, pictured here in 2018, fishes for salmon. (Power to the People)

“They're actually planning for the future,” said Laboucan-Massimo, who toured the community to see the diverse array of climate solutions like solar installations, a solar thermal greenhouse, community gardens, beekeeping, and a run-of-the-river hydro project that produces energy for the region.

“They're planning for the reality of it, and for the changes that are coming.”

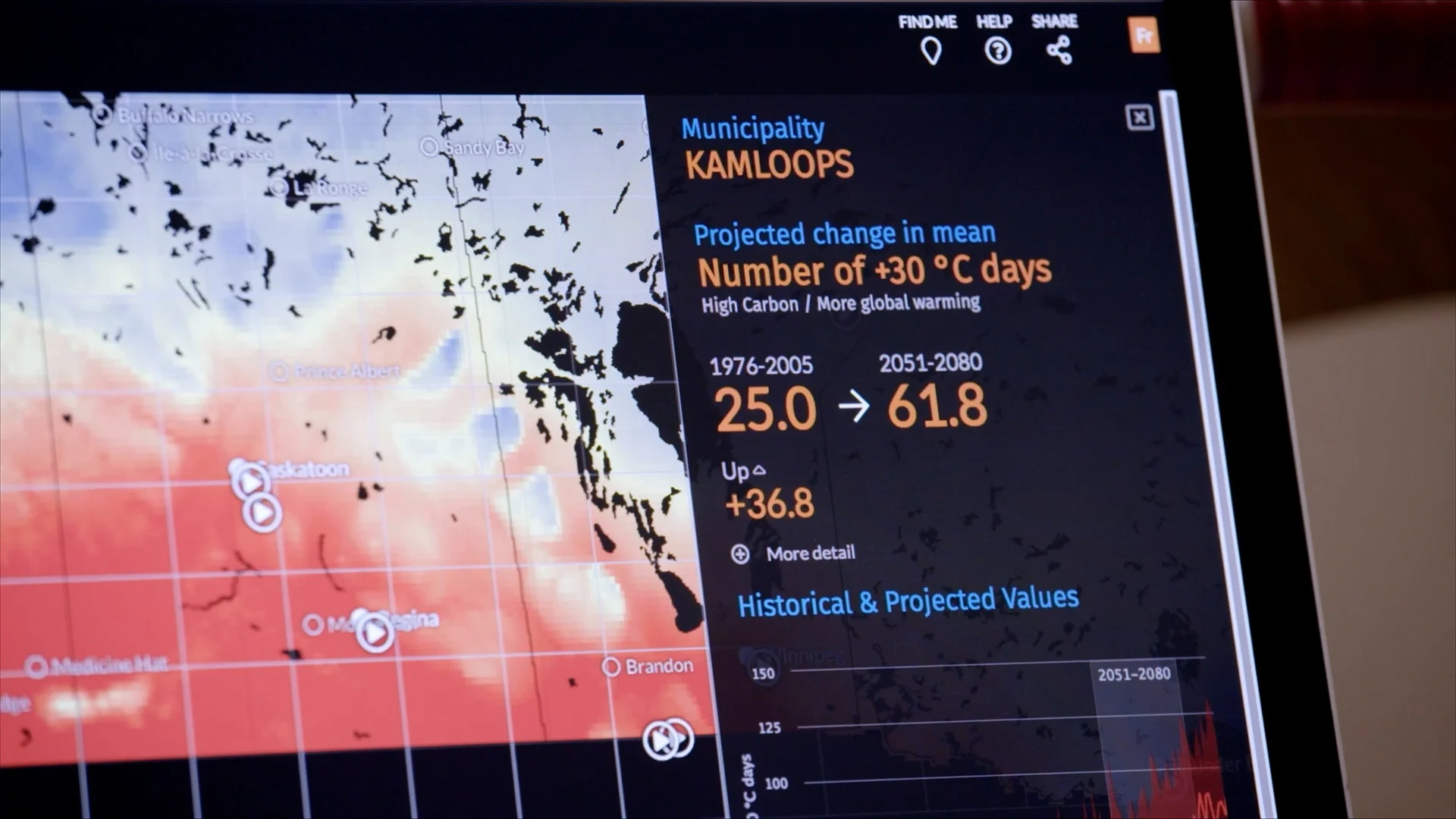

It will be needed. Laboucan-Massimo also visited the Prairie Climate Centre at the University of Winnipeg to find out just what to expect. There they have a Climate Atlas of Canada portal that tells the story of how climate change is going to impact the Great White North. One of the big ways is they expect a more than doubling of plus 30 C days in the coming decades.

READ MORE: Indigenous-owned wind farm is thriving in one of Quebec's windiest regions

Laboucan-Massimo said it was an “intense feeling” filming in Kanaka Bar in 41 C heat, but temperatures hit 55 C in the summer of 2021 — and records keep climbing.

“We need to figure out how to create communities that are designed to buffer and, in some ways, benefit from the changes that are likely to come. Because the changes are going to be sweeping,” said Ian Mauro, the former executive director of the Prairie Climate Centre.

More hotter days are on the horizon for Interior B.C. (Power to the People)

“They're going to be serious. And those communities that are ready for that, they're going to know where their water is coming from and ensure that it's protected.”

More floods and droughts are also expected, along with atmospheric rivers that can cause mudslides and infrastructure damage that can cut communities off from help.

“So all of the water moving through quickly at one time, and then extended periods of drought in the summer when it's hotter and all the water has evaporated,” said Nora Casson, a scientist with the Prairie Climate Centre.

Something Kanaka Bar knows all too well, and is fighting to fix for the future.

Thumbnail image: A solar panel set up in Kanaka Bar has the ability to follow the sun 'like a sunflower.' (Power to the People)