For geothermal power, small earthquakes can cause a big headache

Researchers created a model to reduce the risk of seismic activity at geothermal facilities, and other projects that mess with subsurface pressure.

Alberta’s subsurface zone is getting a little crowded, potentially posing a challenge for geothermal energy operations in the province.

Companies in Alberta have been fracking, a form of waste water disposal in the oil and gas industry, since the 1950s. Carbon capture and storage projects have also been piping CO2 into subsurface formations like depleted gas reservoirs. More recently, plans to set up geothermal energy operations are poised to get involved as well, pumping geothermically heated liquid from and back to reservoirs deep underground.

All of these activities change the pressure and temperature in underground rock formations. If these get high enough they can cause earthquakes, though often small ones. The Alberta Energy Regulator (AER) also offers a map of earthquakes, including so-called induced seismic activity. Factors like depth of the liquid, ground temperature, rock composition, and proximity to a fault line can increase the likelihood of induced seismic activity.

Recent research, which involved modelling Alberta’s subsurface, could be a tool to ensure geothermal operations steer clear from zones with a higher risk of seismic activity, and avoid inducing it themselves.

READ MORE: Fracking-induced earthquakes possible in these Canadian regions, study says

“We've learned over the years that either injection or production can give rise to induced seismicity. But it depends upon the initial conditions in the ground, and it depends upon the behavior of the materials involved,” Maurice Dusseault, professor of earth and environmental sciences at the University of Waterloo and one of the paper’s authors, told The Weather Network.

In general, geothermal power involves pumping liquid — often salty water, sometimes with small amounts of petroleum products — from the subsurface from and back into the geological formation it came from, like porous rock. This liquid is usually heated either by the earth’s core or other processes like the friction between rocks. Once it is pumped up to the surface, the liquid, which can get hotter than 120 C, is used to heat water to produce steam which turns a turbine, producing electricity. The spent liquid is then pumped back into the earth to heat up again.

According to the AER, geothermal energy is expected to produce 294.6 GWh by 2030, enough to power 49,100 average Alberta homes (600 kilowatt hours) for a month. While the AER’s website notes that cheap solar and wind energy “could slow the pace of geothermal commercialization in the province,” it doesn’t rely on the sun shining or a windy day. As such, it can provide energy when solar and wind power can’t operate.

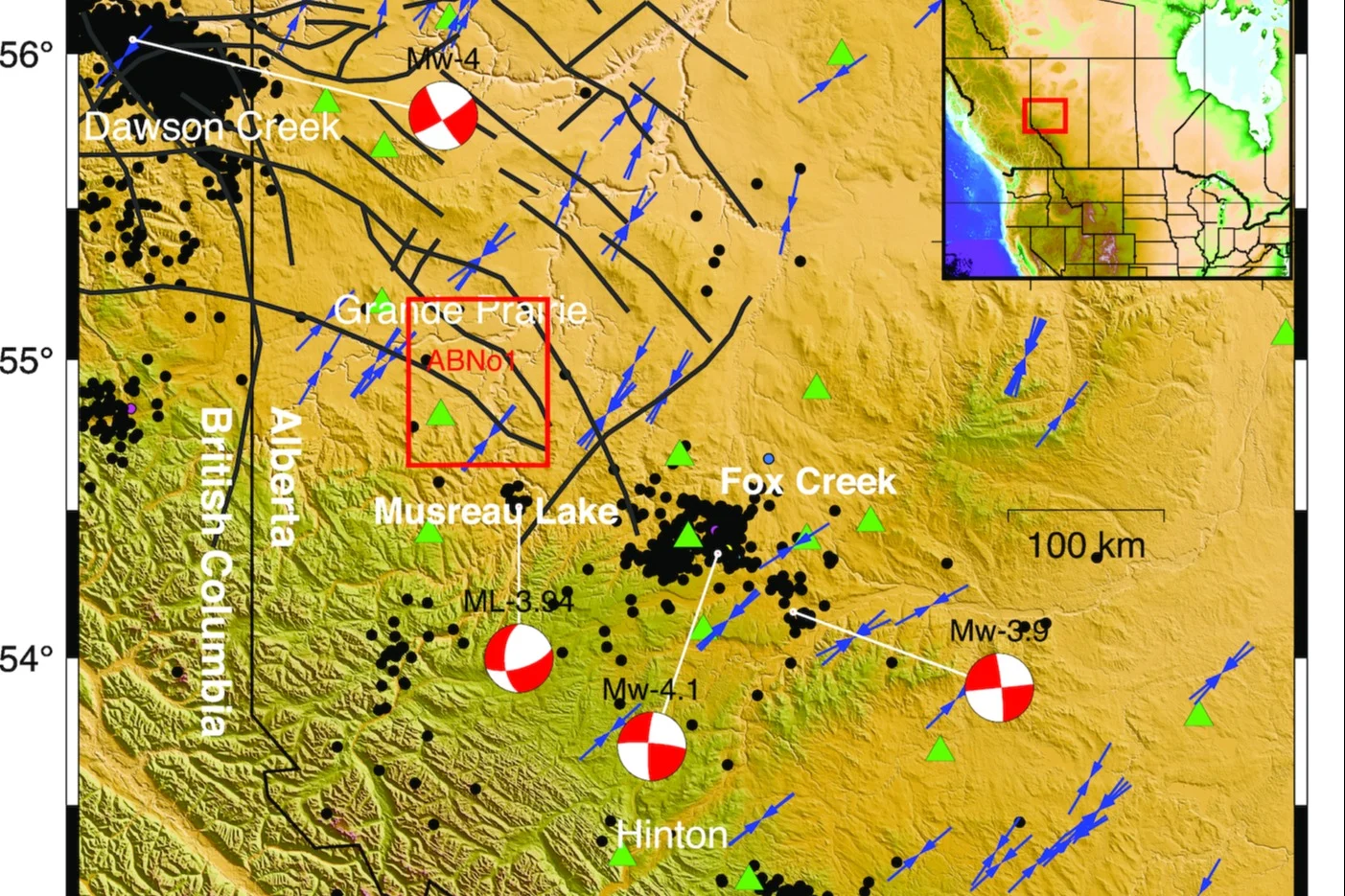

One upcoming development, the Alberta No. 1 geothermal project, is slated to open in the District of Greenview south of Grande Prairie, Alta. The recent paper was also provided to the AER as a risk assessment for their application.

“We're doing everything that we can to understand the risk before we build the facility,” Catherine Hickson, CEO of Alberta No. 1, president of the nonprofit organization Geothermal Canada, and an author listed on the paper, told The Weather Network.

An image taken from a 2023 paper which aims to predict the risk of seismic activity at Alberta geothermal operations. (Supplied)

In the research, Ali Yaghoubi, a researcher who was PhD student at the University of Waterloo’s department of earth and environmental sciences while writing the paper, developed a three-dimensional model of parts of Alberta near the site.

The team used data on several factors including stress and various material qualities such as strength using the analytics platform geoSCOUT. They paired this with data on the location of faults and past earthquakes. Yaghoubi explained that there’s a great deal of uncertainty in terms of these factors: temperature and material in the subsurface at different depths can vary from place to place, for instance. As such, the team developed statistical ranges to represent each factor in an area.

The team then ran different simulations in the model with various factors, including the pressure and temperature changes in the subsurface due to the geothermal plant’s operations. From there, the model can provide a probability of seismic activity in an area under certain conditions.

In all, the team found that the location, despite being located near an area with a lot of fracking, was not likely to see much seismic activity when the facility is up and running. Hickson noted that other geothermal operations could use this model as well when picking a site.

READ MORE: How a Supreme Court case could decide the future of Canadian climate policy

Dusseault said that seismic activity in Alberta, either caused or experienced by geothermal operations, are unlikely to cause damage to the facilities. Most of the subsurface activities in the province don’t happen deep enough, often between three and five kilometers, to cause large earthquakes.

Most likely, they’d be under magnitude four. Some of them could be felt, but would be unlikely to cause any damage. However, he noted, people nearby may find them unnerving.

“But if we were generating repeated earthquakes of magnitude, four, 4.1 … the people in the vicinity are not going to be happy campers,” he said.

Plus, Alberta has a “traffic light” system for seismic activity for developments like geothermal energy. Red, yellow, and green events all confer different magnitudes, which vary depending on the site, how close it is to infrastructure or communities, and other factors. Should a green seismic event occur at the site, nothing needs to happen. A yellow event means that the operation needs to change, for instance, how much pressure it’s producing in the subsurface. A red event (which is a magnitude 3.5 event or higher in the case of Alberta No. 1) means that the operation needs to cease operating altogether, and figure out what the problem is.

While earthquakes aren’t likely to cause any physical damage to a geothermal facility, it can represent a sizable practical and economic challenge. While this has yet to happen in Alberta, one 2009 case in Switzerland saw a geothermal project permanently closed its doors after a magnitude 3.4 earthquake occurred. Shutting down cost them, at the time, £5.35 million.

“Well, I mean, it’s financially catastrophic for projects to be shut down. So that’s a big financial incentive to avoid being shut down,” Dusseault said.

Thumbnail image: A geothermal production well for the Blundell Geothermal Power Plant near Milford, Utah. This well provides 400 degree steam and hot water from deep underground to run the turbines at the power plant. (Jon G. Fuller/VW Pics/ Universal Images Group via Getty Images)