Scientists use gravel to help regrow kelp forests after “The Blob”

A marine heat wave from 2013 to 2016 caused the deaths of many kelp forests, so scientists are exploring how gravel can be used to regrow this aquatic species.

Satellite images over the last few decades show a very somber sight: kelp forests across the world are disappearing, and fast.

“We have lost anywhere between 60 to 70 per cent of bull kelp in the last century,” according to Dr. Louis Druehl, who has been studying kelp for years and is the president of Canadian Kelp Resources.

There are several factors that have led to the decline in kelp, but scientists started noticing significant and widespread declines after the most recent marine heat wave known as “The Blob” between 2013 and 2016. During these years, a large area of unusually warm ocean water formed near Alaska and spread across the coasts of North America and Central America. Ocean temperatures were over 2.5°C warmer than usual in many regions and over 100 million Pacific cod and between 500,000 to 1.2 million birds starved to death due to the harsh conditions.

The Blob caused the collapse of many kelp forests, which experts say is devastating for ocean animals since kelp serves as the foundation of many marine ecosystems. Dr. Chris Neufeld, an Affiliated Researching and Visiting Teaching Faculty at the Bamfield Marine Sciences Centre, recalls what he noticed when he took some of his students out to observe documented kelp forests.

Healthy giant kelp near Bamfield, B.C. Credit: Chris Neufeld

“We started surveying in 2016, which was kind of near the end of that first big marine heatwave,” Neufeld told The Weather Network. “That was the first sense that things had dramatically changed. This heat wave had a direct impact on the kelp through water temperature. When the water temperatures reach a certain threshold the kelp actually starts degrading and just melting basically.”

As scientists started seeing kelp disappear, the fear grew regarding what impacts this would have on other marine life that depend on kelp for survival. Small fish lay eggs and hide in the kelp beds while others eat kelp to survive. This plant also sequesters significant amounts of carbon, so the team at the Bamfield Marine Sciences Centre knew they had to do something about the loss.

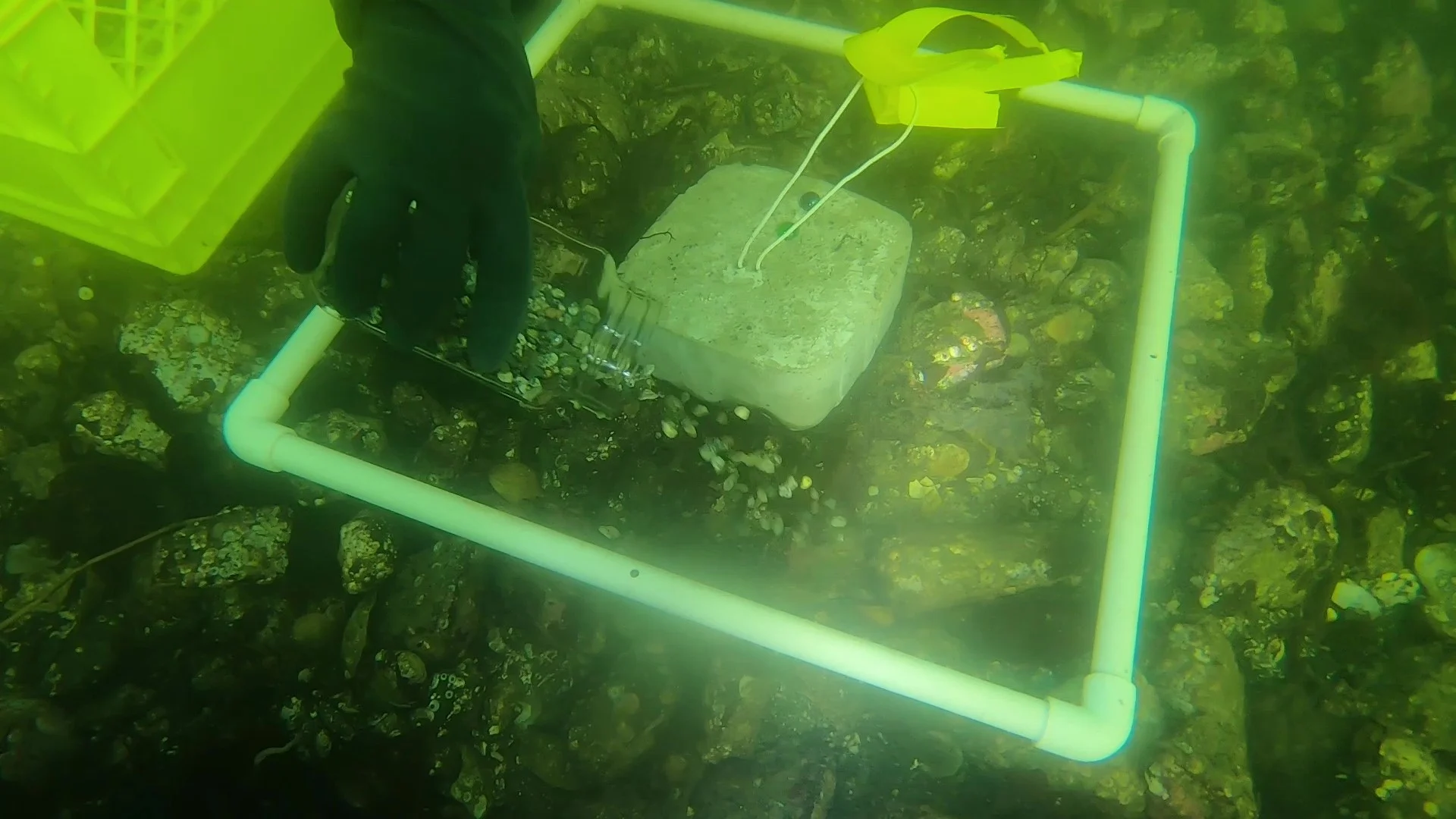

To protect and improve vital marine habitats, a new initiative is exploring a unique approach to promote kelp growth on the ocean floor by using regular old gravel. “The green gravel initiative is essentially grey gravel with little baby kelp attached to it, “ said Druehl.

Deploying green gravel underwater. Credit: Chris Neufeld

Ocean Wise Conservation Association and Canadian Kelp Resources, along with Neufeld and another biologist Sam Starko, have teamed up with an international group of researchers called the Green Gravel Action Group.

Together they are dispersing lab-grown kelp on pieces of gravel and placing them in parts of the ocean where they predict the kelp will survive.

“It is a different way of reintroducing kelp species that have either been lost in an area or are endangered,” added Druehl.

While kelp farming has become popular over the years, the green gravel method is potentially more effective because the kelp is introduced directly into the ocean and bypasses creating seaweed farms and the agriculture process. However, there are a few obstacles the team needs to overcome for this to be successful.

“We don’t want to reseed kelp in areas where future conditions are not hospitable for the kelp,” said Neufeld. “That is why we have spent so much time trying to understand the drivers and factors that have caused the decline, and understanding how the climate is changing so we can find places where the kelp may have been lost, but it is a suitable place for restoration because we think the conditions there will be favourable for kelp.”

The researchers say that an important observation they have made is that the water near the shore is cooler than the water reaching into Howe Sound, and that plays an important role when it comes to deciding which types of kelp are planted and where.

“We can use our knowledge of the genetics of these populations to try and find heat resistant strains of kelp and use those types of ‘super kelp’ to reseed in these areas where they have been lost,” added Neufeld.

Over the next few months the researchers will be monitoring the different kelp seeds to determine which ones tolerate warmer waters and other factors, like the best age to plant the kelp and what size rocks to use, all in hopes of reviving the lost underwater forest.