Nature is in its worst shape in human history, UN report

The facts are alarming, but the report states that it is not too late to fix the problem.

Governments from 130 countries around the world are meeting to find a working formula that will fully protect 30 per cent of Earth’s surface and sustainably manage another 20 per cent by 2030. This based on a recent scientific report on biodiversity that specifies the efforts that need to be made to save global ecosystems while limiting global warming.

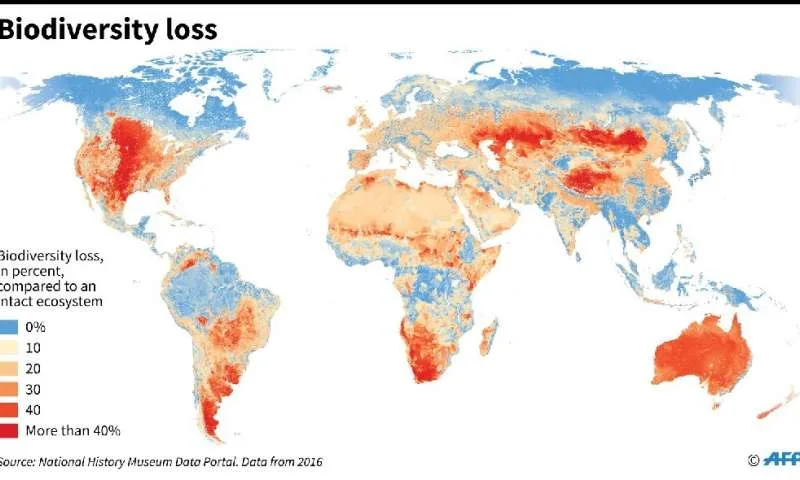

The report states human activity on Earth has put over one million species are at risk of extinction, and species loss is accelerating tens or hundreds of times faster than the natural rate of biodiversity loss occurred in the past. While the facts are alarming, the report states that it is not too late to fix the problem.

A “global deal for nature” was initially proposed by researchers from around the world in 2017 along with many other climate deals pushed forward during the Paris climate accord. It outlined what it would take to keep our planet "alive and kicking" as some put it.

Marine ecosystems are also suffering, and currently one third of ocean fish stocks are in decline and the rest, except for a few, are harvested at the very edge of sustainability.

On land, the problems are multiple and affect so many species, it is hard to decide where to start. For instance, a dramatic die-off of pollinating insects, especially bees, threatens essential crops which provide sustainability for many countries. Productivity from these crops is expected to drop, and some are even likely to be wiped-out completely.

A total of 20 10-year targets adopted in 2010 under the United Nations “biodiversity treaty” aim to expand protected areas, slow species and forest loss, and reduce pollution, will, with one or two exceptions, fail badly. The current 1800 page report, elaborated by 400 experts, is designed to increase the success of the proposed actions but needs strict governmental action along with continuous scientific guidance.

In the past, conservation biology has focused on the preservation of species like the panda or polar bear, and many less “charismatic” animals and plants that humanity is harvesting, eating, crowding and poisoning. According to United Nations biodiversity chief, Robert Watson, that focus has changed in recent decades. Before biodiversity impact was just tackled from a more environmental perspective, whereas today we are more concerned with nature being crucial for food production, to obtain pure water, for medicines and even for social cohesion.

We are much more concerned with climate change, and with finding ways to cut back on greenhouse gas emissions, yet since 2014, an area of tropical forest the size of England has been destroyed, mainly due to the global demand for beef, soy beans, biofuels and palm oil. Agriculture accounts for at least a quarter of greenhouse gas emissions, and it is essential that in record time we find more sustainable ways to manage our land and all the goods it produces.

The IPCC report that was released in 2018 made it as clear as water - if we want to keep global temperature rise under 1.5°C, the world must reduce greenhouse gas emissions 45 per cent by 2030. Earth must become a neutral carbon planet at least by 2050.

The UN report moves in this direction, but it is only an initial road map for what needs to be done if we want to preserve nature. A global movement is needed to convince all governments and the private sector to act, and act now. We have the science, but we really need humanity to step up.