Avalanche Canada establishes first Newfoundland & Labrador field team

It was years ago, but Ryan Crocker still remembers the sensation of being swept up in an avalanche in Woody Point.

"You don't realize the power of the snow, until it starts moving," said Crocker, who was a teenager at the time.

"Once the snow picks up and starts going, it's a completely different beast. You just kind of fall down through it. It just kinda takes you. There's nothing that you can do."

The slide was a small one, and shallow, and Crocker was lucky to be able to dig himself out, with friends nearby to help. But the experience has stuck with him, and in his job as a backcountry guide and owner of Mantle Board Shoppe in Woody Point, he sees reminders of such dangers everywhere. Last spring, he saw four avalanches while he was out in the mountains, he said, one of them triggered by a snowmobile.

The field team digs a snow profile in the Gros Morne backcountry to check on conditions. (Submitted by Peter Thurlow)

That's part of the reason he welcomes the news that a field team for Avalanche Canada has set up shop in the Gros Morne area, the first outpost in Newfoundland and Labrador for the non-profit organization, which promotes avalanche safety and, in Western Canada, issues avalanche forecasts throughout the winter.

Any type of forecasting is far off and might not suit the region's terrain at all. In its first full winter of operations, the field team is taking baby steps into the snowpack, digging pits and test sites in the mountains from the Bay of Islands through Gros Morne to create a snapshot of its snow base and find weak spots and strengths.

"Our main objectives for this year is to assess the needs for the region. So, trying to figure out what kind of avalanche products are going to work here in Newfoundland," said Andy Nichols, the field team's leader, based in Rocky Harbour.

BACKCOUNTRY USE 'EXPLODING'

Federal funding gave Avalanche Canada the green light for its Newfoundland field team, but the need for it has been growing for years, Nichols said.

"We definitely see with the increase in users and the better equipment people have — both with snowmobiles and with backcountry skiing and snowboarding — that people are getting farther into the mountains, more often, and getting themselves in more risky situations," he told CBC Radio's Newfoundland Morning.

While Gros Morne's terrain is vast and it's easy to be alone in its winter wilderness, Crocker said increasingly crowded parking lots and trailheads tell the tale of how many users are out exploring on any given day.

The field team has posted safety information at several avalanche-prone areas on Newfoundland's west coast, including this one at a trailhead in the Blow Me Down Mountains outside Corner Brook. (Submitted by Andy Nichols)

"With the new sleds that are out now, there isn't a hill in Newfoundland that someone couldn't climb in a snowmobile. And that puts snowmobilers directly in the path of avalanches, and avalanche terrain," he said.

Crocker worries people's avalanche education isn't keeping pace with the increasing sophistication and power of those machines. His business sells safety gear like beacons, probes and shovels, and he always carries it on his backcountry trips, but said there's a wider sentiment that "avalanches don't occur in Newfoundland, and that's just not true."

The province actually has a lengthy history with the natural phenomena. Canada's first recorded avalanche fatalities date back to Nain in 1781 or '82, when 22 people died in a slide, and avalanches have been noted from that tip of Labrador right to the Battery neighbourhood of St. John's.

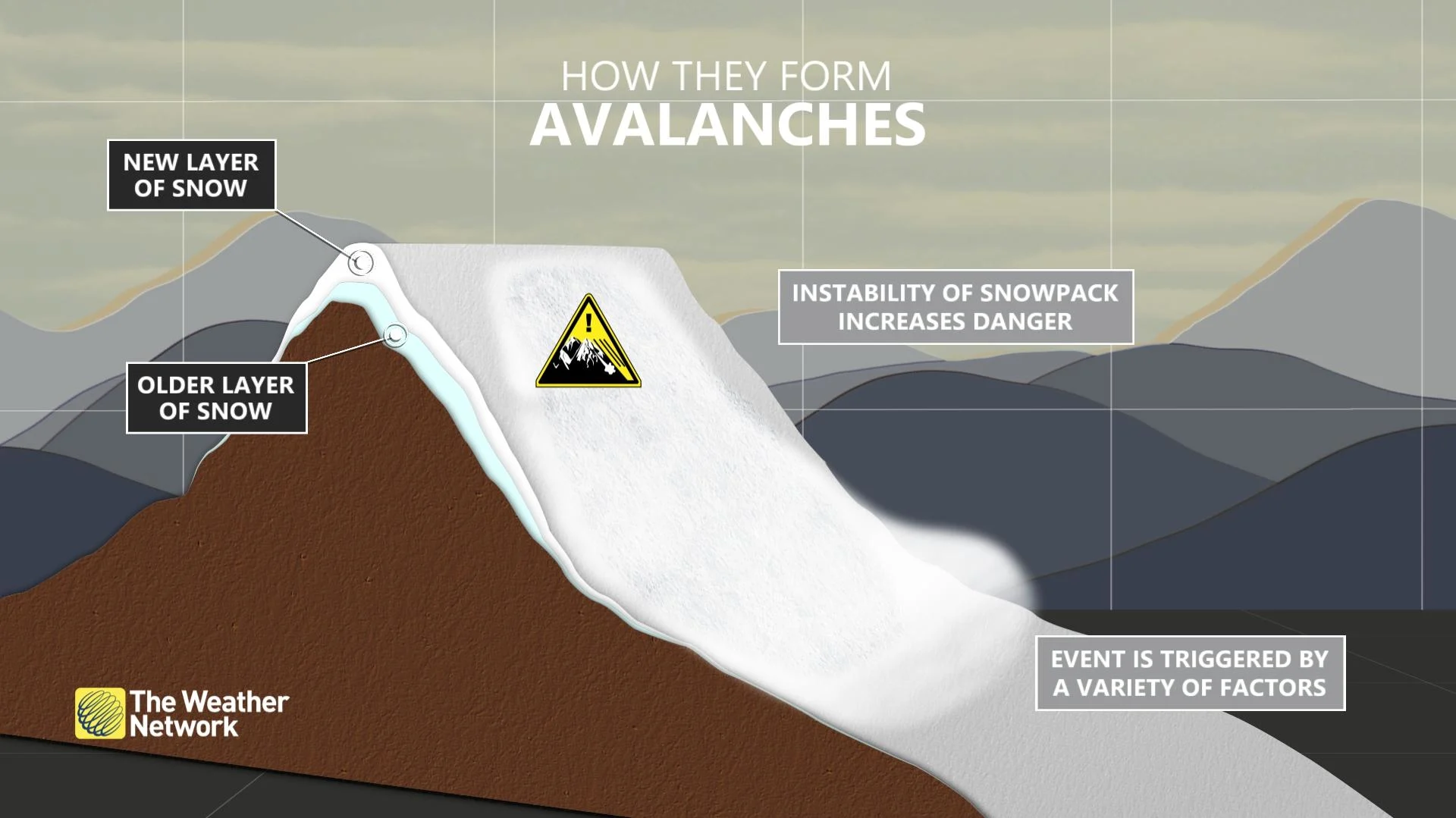

HUMAN-TRIGGERED AVALANCHES COULD BE ON THE RISE, HOW TO STAY SAFE:

AVALANCHE EDUCATION

Avalanches are classified on a scale of one to five: from relatively harmless slides to those that could bury a village.

Nichols said levels 1 through 3 are "pretty prevalent" in Newfoundland and Labrador, but the strength is less important than the circumstances surrounding it: finding yourself in front of the full force of a small slide can be a deadly prospect.

A major focus for the field team is on education, and Nichols has been leading safety courses to satisfy people's appetites to stay safe in the backcountry.

"There's been a really big demand for education in the past four or five years for sure, so we're getting a lot more people who are getting educated,"he said.

As the team scouts the snow this year, they're also posting safety information and reports to social media to boost awareness.

Crocker said his business — prior to pandemic restrictions — was taking off, with Americans and Canadians increasingly showing interest in Gros Morne as they become weary of long ski resort lines and crowded Quebec backcountry hot spots like the Chic-Choc Mountains.

"People are burnt out with that, and they're looking for the next place, and they're looking for the next thing," Crocker.

Getting better avalanche safety information out there will bring in more tourists, he said, as well as locals.

"The safer that we can make the backcountry, the better it will be for everybody," he said.

While the Avalanche Canada team is focusing this year on the area from Gros Morne through Bay of Islands, Nichols said they hope to expand their efforts farther afield in years to come.

This article was originally published for CBC News. Contains files from Newfoundland Morning.