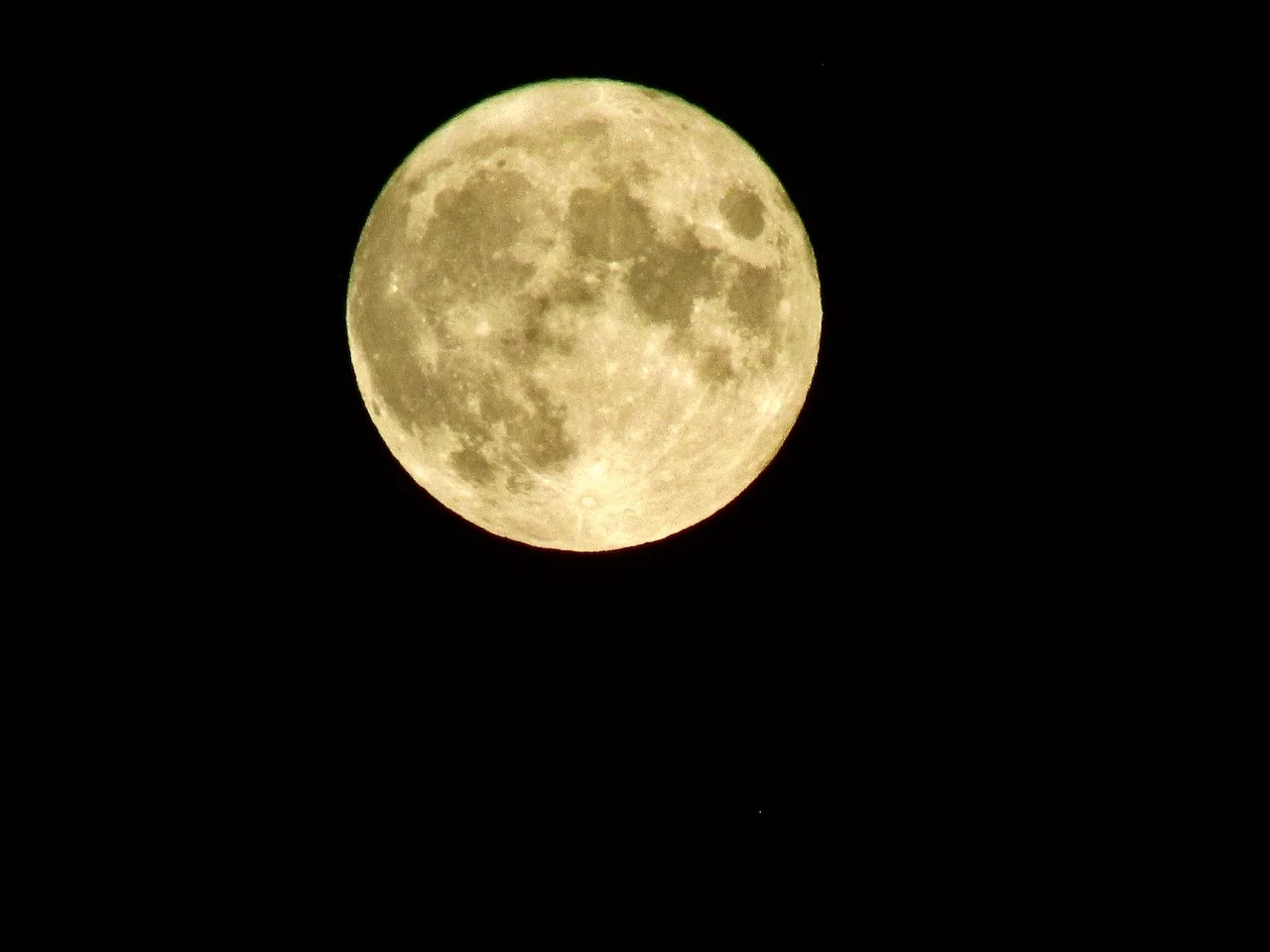

Can't sleep? The moon may be the culprit, new study shows

The new study showed the moon's influence on sleep duration and quality, with some participants in a multi-year experiment seeing shorter rest on nights during the waxing period compared to what was observed in the waning interval.

Getting a good night sleep can be difficult sometimes as there are many reasons to keep us distracted and awake at night. But perhaps the odd time your lack of sleep could be due to the influence of the moon.

While it's not a new concept, with previous studies conducted on the moon's potential health effects, a new analysis revealed its impacts on sleep duration. Some of those in a multi-year experiment experienced shorter rest on nights during the waxing period compared to what was observed in the waning interval.

SEE ALSO: Moon ‘wobble’ will amplify devastating coastal flooding by mid-2030s, says NASA

The study involved the use of one-night sleep recordings from 852 people residing in Uppsala, Sweden, at the time. According to the researchers, the examination illustrates one of the largest polysomnography investigations (sleep study) into the association of the 29.53-day-long lunar cycle with sleep among men and women across a wide age range (22–81 years).

Sleep onset, duration, and quality during the one night were recorded for the study, with observations documented for several years.

(Nathan Howes)

MORE IMPACTS SEEN IN MEN, MOON'S ILLUMINATION SHIFTS BETWEEN PERIODS

The recorded differences in sleep between the waxing and waning phases may be propelled by the moon's illumination.

Researchers found that from the day after the new moon until the day of the full moon (waxing period), its light increases and the timing of the meridian of the moon is slowly moved from noon toward midnight.

In variation, however, from the day after the full moon until the day of the new moon (waning period), its illumination goes down and the meridian's timing of the moon is gradually shifted from early-night hours to noon.

Compared to participants whose sleep was recorded during the waning phase, the results of the study found that partakers whose sleep was documented during the nights of the waxing phase slept shorter, spent less time in sleep stages, were awake longer after sleep onset, and had a lower sleep efficiency.

A plane passes in front of a full moon in Arlington, Va. (NASA/Joel Kowsky)

While both sexes were impacted, the findings suggest that the effects of the lunar cycle on human sleep are more noticeable among men, the researchers said. Men whose sleep was observed during the waxing phase had lower sleep efficiency and were longer awake than those whose rest was measured during the waning period.

On waxing nights, sleep in men had decreased by more than 20 minutes. As well, they experienced 3.4 per cent lower sleep efficiency and greater disruptions to the length of rest during the same period.

Despite results showing more of an impact on men, there was still some influence on women. The paper indicates women in the study, on average, slept nearly 12 minutes less on nights during the waxing period, compared to waning nights.

"To our best knowledge, in contrast to all previously published studies known to us, a major strength of the present study is that we accounted for sleep disturbances prevalent in the general population (e.g., insomnia and obstructive sleep apnea) when investigating the lunar cycle and sleep association," the researchers wrote in the study.

VIDEO: THE TEMPERATURE YOU SHOULD BE SLEEPING AT REVEALED

NO CONCRETE CONCLUSIONS ON 'CASUALITY'

However, the research is observational, so no firm conclusions can be drawn on the "causality" of the relations, the authors stated in the study.

But the outcome of the study does indicate something appears to be making people sleep differently, combined with the brightness and fullness of the moon on any night. The difficulty lies in accurately determining the extent of the results.

"Our study, of course, cannot disentangle whether the association of sleep with the lunar cycle was causal or just correlative," says Christian Benedict, associate professor at Uppsala University's Department of Neuroscience, and corresponding author of the study, in a news release.

Thumbnail courtesy of NASA.

Follow Nathan Howes on Twitter.