Tracking COVID-19 in sewage, Canada’s making some major moves

What you flush down the toilet could help researchers big time in the fight against COVID-19.

Think of your flush as adding to a forecast of potential disease in your area. In fact, scientists may even thank you for it.

“We’ve been collecting samples of the wastewater that comes into the [treatment] plant,” says Marc Habash, Associate Professor at the University of Guelph’s School of Environmental Sciences. “And then, through different processes, we concentrate those samples and extract the genetic material from that sample. We then look for specific genetic sequences that relate to that virus. And using that information, it can tell us if that virus is present in the community that is being served by that wastewater treatment plant.”

There are multiple regions across Canada that are tracing concentrations of COVID-19 in sewage, including Vancouver, Calgary, Toronto, Ottawa and Montreal, following the lead of researchers in Europe who first tried to track COVID-19 in their wastewater, and they found they were able to predict outbreaks before they occur.

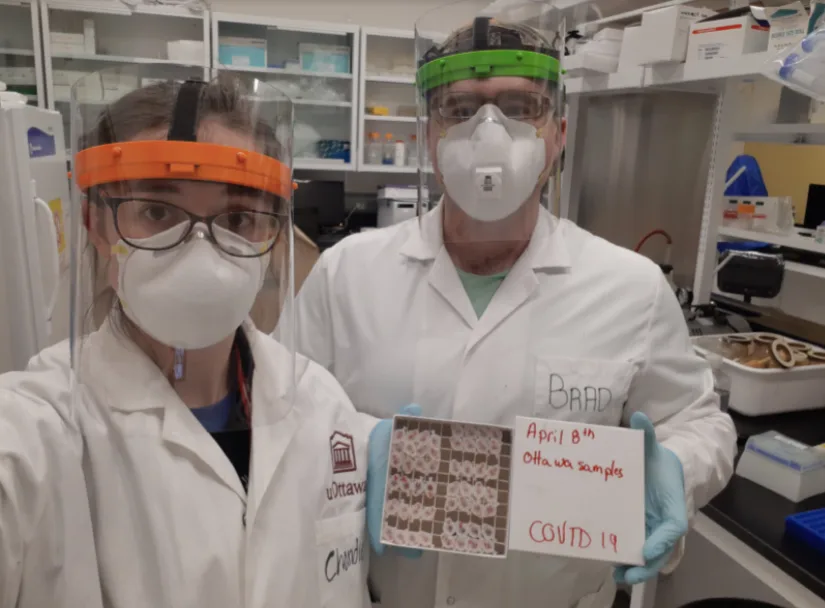

Prof. Robert Delatolla at the University of Ottawa’s Faculty of Engineering is working with a large team tracking sewage in Ottawa and Gatineau, tracing the ribonucleic acid (RNA) of the virus and the proteins.

Delatolla’s team found evidence that COVID-19 concentrations chance within sewage, with spikes and declines that match trends reported by public health workers. In fact, spikes in sewage were detected even before being reported by nasal testing, and even shows results from asymptomatic hosts.

Photo: Elisabeth Mercier and Patrick D’Aoust test samples in Ottawa and Gatineau

“We are now taking this information and giving daily reports to Ottawa Public Health,” Delatolla told The Weather Network. “They now have daily numbers of COVID concentration in Ottawa’s wastewater.”

The teams in Ottawa seem to be the furthest ahead in terms of making their findings useful to public health in real time, starting in late September. Many other research teams hope to have the same outcome.

“Within a month we hope to be reporting to Toronto Public Health,” says Ryerson University Prof. Claire Oswald, who is working with Ryerson Urban Water.

One of the delays Toronto’s teams are experiencing with tracing is the fact that the old areas of the city still use a combined sewer system: when it rains or too much snow melts, runoff can get mixed in with sewage, throwing off the numbers.

The end goal for many of these teams would be to have real-time information delivered to their public health units. All the researchers I spoke to commented that sewage tracing is an excellent complement to all the testing that is being done nationwide.

“I would hope this becomes a routine part of testing,” says Habash in Guelph. “We can use this to help forecast when this organism may start to spike. This could also really help public health units direct their efforts and maximize what they are able to do and who they are able to help.”

WATCH BELOW: IS IT COVID-19 OR SEASONAL FLU? SPOT THE DIFFERENCES

Another goal with sewage testing is to use it on a microscale, for example in a long-term care facility or a University. This would help teams manage COVID19 outbreaks in very vulnerable close contact groups.

This method proved useful at a University in Arizona. As the sewage was being traced for COVID-19 on campus, a spike in concentration was detected. Teams then did rapid testing of all the students and found two positive cases. Proper social distancing measures were taken and the teams believe that the spread was rapidly reduced and an outbreak was avoided.

Watch the video up top as I chat with three Canadian researchers who are currently working on this interesting project.