How broadcasting the sounds of a healthy reef may help coral recovery

A healthy coral reef is a noisy place. Researcher Tim Gordon calls it a 'symphony,' made up of notes like the 'whooping' from clownfish, the crunching of parrotfish grazing through coral, and many thousands of shrimp snapping their claws.

These are the sounds of home for a multitude of species, including communities of fish that are crucial to the health of the reef. Most of these species spend their early lives in the open ocean, to avoid predators, and -- when they're big enough -- head back to reefs to settle.

But, as Gordon points out, that trip isn't like in the movies: There are no friendly sea turtles to point the way. Instead, juvenile fish have to rely on the reef's smells and sounds to guide them to their new homes.

In reefs that are suffering under stressors climate change and pollution, however, those essential scent and sound markers may be missing, making them less attractive property for young fish.

That's where Gordon and his team come in to play.

"[We thought] if one of the things that a degraded reef is missing is its sounds, well, that is something that on a local level we can replace," he told the Guardian.

And, according to a study the team published recently in Nature Communications, they seem to be onto something.

The researchers placed speakers on patches of coral rubble on the Great Barrier Reef during a 'recruitment season' (the time of year young fish typically move into their new living quarters) in late 2017. The loudspeakers played the soundscapes of a healthy coral reef for 40 days, during which time the team surveyed the number of damselfish attracted to each 'acoustically enriched' site, versus those with no speaker, and those with a speaker installed but no sound.

The results look pretty convincing.

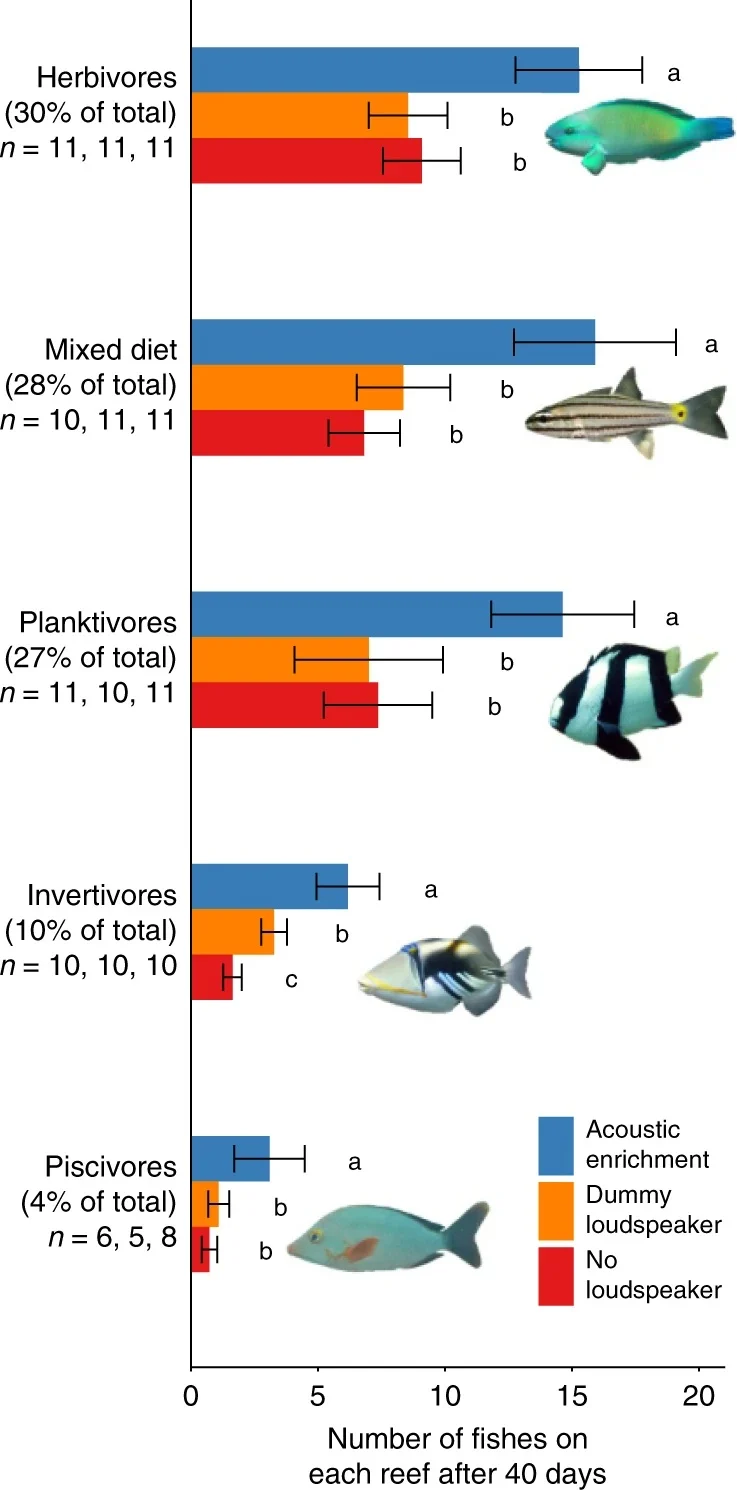

Sites broadcasting the sounds of a healthy reef attracted twice as many young damselfish (the species the team selected to survey) as the silent ones. Researchers also found that the enhanced sites attracted more species across the board, from plankton-eaters all the way up to fish that eat other fish, increasing biodiversity overall.

Effects of acoustic enrichment on different trophic groups. Mean ± SE juvenile fish abundance in different trophic guilds on experimental patch reefs. Y-axis labels give the proportion of all fishes and the frequency of occurrence (number of populated reefs in each loudspeaker treatment) represented by each trophic guild. Mixed-effects models revealed significant effects of loudspeaker treatment in all five trophic guilds; different letters associated with boxplots represent significant differences in post-hoc Tukey's HSD tests (Supplementary Table 1). Images of fish are taken from the Lizard Island Field Guide (lifg.australianmuseum.net.au), licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 License (creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/). Image courtesy Nature Communications.

"Climate change and warming seas have caused more damage to coral reefs worldwide in the past four years than they have in the whole of recorded history," said Gordon in 2017. He based his research in part on recordings of the 'animal orchestra' of reefs from just a few years ago to the present silence.

Gordon hopes that, by boosting the volume of a struggling reef's nature noises, it might help to "kickstart a recovery." But luring young fish into the reefs is only part of the solution.

"This is potentially a useful tool for attracting fish towards areas of degraded habitat, but it is not a way of solving the coral reef crisis," Gordon told the Guardian. "It is not a way of bringing back a whole reef to life on its own."

Sources: Nature Communications | The Guardian | University of Exeter/Tim Gordon |