Here's what the world would lose if bumblebees disappeared

Here's why the world needs bumblebees, according to an expert.

I study insects for a living, and bumblebees are by far my favourite. They’re the most charismatic and friendly critters you’re likely to see out and about. Sadly, your chances of seeing a bumblebee in Europe and North America have dropped by a third since 1970, according to new research.

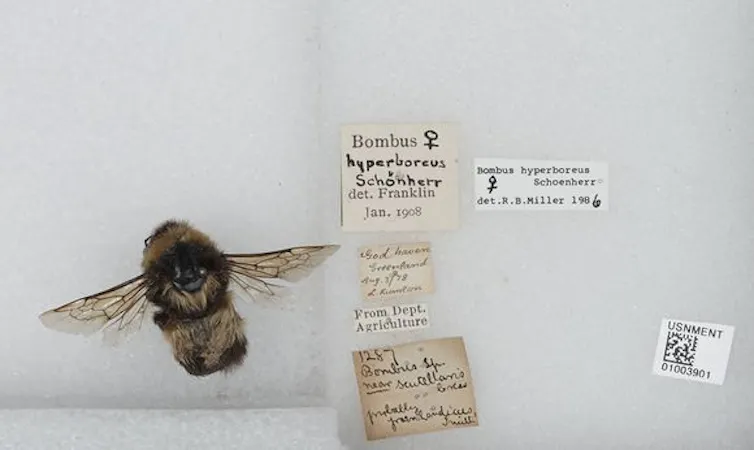

Across Europe, we have 68 species of bumblebee, but rising global temperatures and unpredictable weather have forced some to abandon southern regions. As a result, roughly half of these species are in decline, with 16 already endangered. Many of these species are found in only a handful of places, like Bombus hyperboreus, which only lives in Scandinavian tundra. As the climate changes, these bees will be left with nowhere to go and could die out altogether.

Their thick, fuzzy jackets and loud drone set these bees apart from other insects, and they’re a familiar sight across much of the world. There are even tropical bumblebees that can be found in the Amazon rainforest. But what might a world without them look like?

Bombus hyperboreus is listed as ‘Vulnerable’ by the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN). Smithsonian Institution/Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA

EXPERT POLLINATORS

Over three-quarters of the world’s crops benefit from insect pollination, valued at USD$235-577bn annually. Out of the 124 staple crops grown for human consumption, 70% depend on insect pollination.

Though the plight of honeybees tends to draw the most attention, recent research suggests that bumblebees are far more efficient pollinators.

They are bigger and hairier and so can carry more pollen. They also groom themselves less and can transfer pollen more effectively to fertilise plants. They behave differently around flowers, moving methodically to cover each flower in a patch, whereas honeybees tend to move randomly between flowers in a patch.

Bumblebees are also hardier than honeybees and will continue to pollinate under strong winds or rain. We could still grow food without bumblebees, but we might struggle to get enough and our diet wouldn’t be as diverse.

Bumblebees are masters of “buzz pollination”. They can vibrate at a particularly high frequency (as much as 400Hz) near flowers, to release pollen that’s otherwise hard to reach. Bumblebees are among a small minority of pollinating insects that can do this, and tomatoes, potatoes and blueberries rely on it to reproduce.

MORE IN POLLINATORS: SAVING HONEYBEES

THE INNER LIVES OF BUMBLEBEES

Like honeybees, bumbles are social creatures and live in hives. They are ruled by a single queen who is supported by her daughters (the workers) and a few sons (drones).

While honeybees typically form hives of around 30,000 individuals, that can be almost as big as a person, bumbles live far more modestly. Their hives host around 100 bees and are small enough to fit in a plant pot.

As temperatures rise in early spring, the enormous queens that hibernated underground over winter wake up and search for nectar and pollen, and a suitable nesting site for the year. They aren’t picky – tree hollows, bird boxes and the space beneath garden sheds will all do.

The common carder bee (Bombus pascuorum) forms an above-ground nest in grass and moss. Panoramedia/Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA

Workers guard the nest and forage for the queen, who lays eggs in late summer for male drones and new queens. These both leave to mate with bees from other hives, while new queens feed on pollen and nectar, storing the energy as fat inside their bodies so that they can hibernate through the winter and emerge in spring, to begin the cycle anew. The workers and drones meanwhile die off each winter.

Not all bees live in hives and make honey though. The cuckoo bee, for instance, belongs to the bumblebee family, but is something of a black sheep. Cuckoos disguise themselves as other bumblebee species, hide their eggs in their hives, and allow the hard-working hosts to raise and care for them. So well disguised are these parasites that even entomologists struggle to identify them in the wild.

While honeybees are generalists and feed on anything they can find, bumblebees tend to have a highly specialised diet, and flowers have evolved close relationships with particular species. Plants like red clover have long, complex flower tubes that only long-tongued species like Bombus hortorum can reach. In highly specialised systems like this, the loss of the plant or the pollinator could lead to the loss of the other, causing a cascade of extinctions.

Read more: Beyond honey bees: Wild bees are also key pollinators, and some species are disappearing

SILENT SPRING?

Climate change isn’t the only threat to bumblebees. Changes in how land is used – more pesticide-rich agriculture, less wild grassland – mean less forage. This has caused massive declines, even fairly recently. Cullum’s humble bumble (Bombus cullumanus) has declined by 80% globally since 2010

But wild bumbles are resilient and respond faster to improvements in their habitat, such as wildflower strips, than honeybees. In the UK, the short-haired bumblebee (Bombus subterraneus) was declared extinct in 2000, but collaboration between the RSPB and Bumblebee Conservation Trust helped reintroduce the species to sites in southern England, near Dungeness and Romney Marsh.

Corridors of wildflower-rich meadow can connect fragmented bumblebee habitats. Mehmet Kürşat Değer/Unsplash, CC BY-SA

If the habitats of species with smaller ranges can be improved and expanded, there’s hope for preventing extinctions as the climate warms. The insect charity Buglife is working on a network of “B-Lines” – wildflower meadow strips that can link up fragments of useful habitat and ensure bumblebees aren’t trapped in these shrinking pockets.

Bumblebees give us a colourful diet of fruit and vegetables through their particular brand of pollination. We owe it to our fuzzy friends to help them survive the great changes that climate change will bring to their world.

Philip Donkersley, Senior Research Associate in Entomology, Lancaster University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article. Thumbnail image courtesy: Unsplash.