Canadian Arctic fossils may be the oldest animal ever found, study suggests

Fossils that formed 890 million years ago in what is now the Northwest Territories may be by far the oldest evidence of animal life ever found, a controversial new Canadian study suggests.

The tiny fossils are "possible" remains of the skeleton of an ancient sponge, says a new study by Elizabeth Turner, professor of earth sciences at Laurentian University in Sudbury, Ont., published in Nature today.

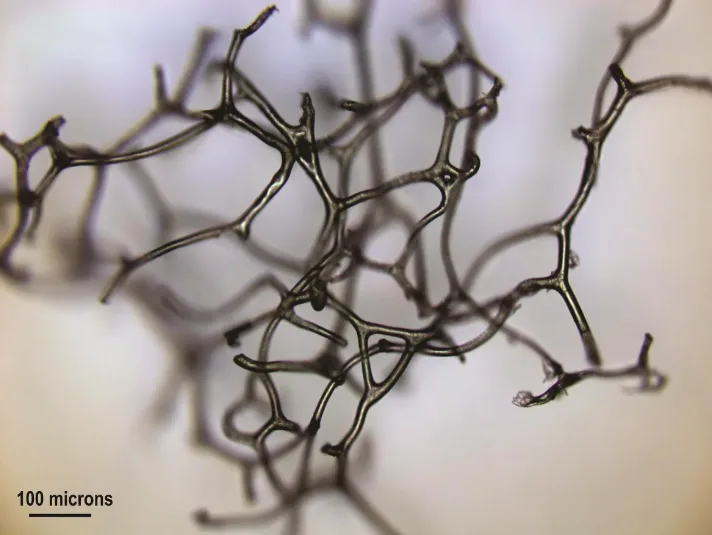

These microscopic 890-million-year-old fossils found in the Northwest Territories are thought to be the remains of an ancient sponge. If that's the case, they would be by far the oldest animal fossils ever found. (Elizabeth Turner/Laurentian University)

A cautious news release from the journal titled "Potential Evidence for the Earliest Animal Life" said, "the findings, if verified, may represent the earliest known fossilized animal body and may pre-date the next-oldest undisputed sponge fossils by around 350 million years."

That would also make them more than 300 million years older than the oldest confirmed animal fossil until now, Dickinsonia, an elliptical, leaf-like marine creature that grew up to 1.22 metres long and lived 558 million years ago.

The previous oldest confirmed sponge — widely considered to be the earliest group of animals — lived 535 million years ago.

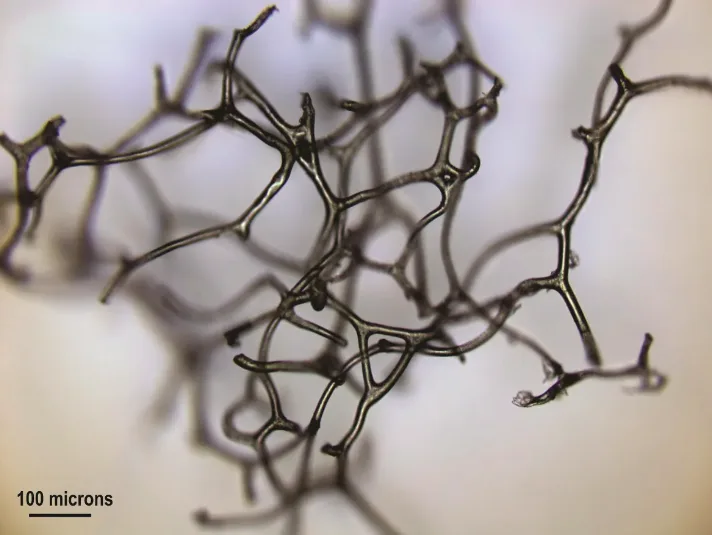

This is the skeleton of a modern bath sponge or horny sponge from Greece seen under a microscope, which has a similar structure to the fossils. (Elizabeth Turner/Laurentian University)

Turner said she first found the fossils in pockets and crevices of ancient reefs called stromatolites built by photosynthetic microbes called cyanobacteria while studying the microbes themselves for her PhD in the 1990s.

While the ancient reefs are in the Arctic now — more specifically, their fossilized remains are limestone deposits in the Mackenzie Mountains, which are located in the Northwest Territories near the Yukon border — 890 million years ago, they were much closer to the equator in the middle of a supercontinent called Rodinia, in a shallow inland sea.

The fossils were worm-like and half the width of a human hair, branching and then rejoining. Turner was intrigued, as they were complex structures and she suspected they weren't made by microbes. She puzzled over them for decades, returning periodically to gather more samples.

Then recently, Joachim Reitner in Germany, Robert Riding in the U.S. and Jeong-Hyun Lee in Korea, published research showing how similar fossils could be formed from horny sponges, the type of sponge used to make commercial bath sponges.

"They are truly identical to the ones that I had in my much older rocks," Turner said. "There weren't any other truly viable interpretations of the material."

Elizabeth Turner, a Laurentian University earth sciences professor, was the author of the new paper. In this photo, she does unrelated field work on northern Baffin Island in Nunavut. (C. Gilbert)

The reef pockets and crevices in the Mackenzie Mountains where the worm-like sponge fossils were found are similar to the environments where sponges live today, she said.

They were too dark for the cyanobacteria themselves to live in, so the microbes wouldn't compete with the sponges for space and other resources. But it was close enough for a sponge to capture some of the oxygen produced by the microbes, which was in short supply at that time.

The microbes might also produce a source of food in the form of slime — something their modern relatives still do, giving them their nickname, "pond scum."

WHAT OTHER SCIENTISTS THINK

In an unusual move, since peer review is usually anonymous, Nature disclosed that Reitner, Riding and Lee had all peer reviewed Turner's article. Riding and Lee both confirmed they think Turner's interpretation is correct.

Riding says it's a "very interesting discovery."

"The orderliness and neatness of this pattern, I think, is very distinctive," he told CBC News in a phone interview, noting that the fossils are exceptionally well-preserved. "And if I found that pattern in younger rocks, I would say for sure that it was a sponge."

He said that sponges have long been thought to be the earliest animal and were predicted to have evolved around the time that these fossils would have formed.

That said, Riding acknowledged that the simplicity of the fossils and their extraordinary age mean some other scientists might need more convincing.

He thinks more people will start to look for these types of fossils, and may start to check them for the biochemical fingerprints left behind by sponges, which have been found in younger fossils. That would convince the doubters, he said, but added that "in my opinion, it is a sponge fossil."

This is one of the sites in the Mackenzie Mountains of the Northwest Territories. The mountains contain limestone from huge ancient reefs, which is where the fossils were found. (Elizabeth Turner/Laurentian University)

SOME RESEARCHERS SKEPTICAL

Other researchers contacted by CBC News were more skeptical.

Jonathan Antcliffe is a paleontologist at the University of Lausanne in Switzerland who has previously disputed other "oldest sponge" fossil discoveries.

He said fossils are usually identified by unique and distinctive characteristics for that group, and there are many for sponges, including hard skeletal elements called spicules that fossilize well. Those were not found in this fossil.

While horny sponges don't have spicules, Antcliffe said they're one of the "weirdest" groups of modern sponges. He added that spicules should exist in even the earliest sponges, since they exist in a microbe that is thought to be the ancestor of sponges.

Unlike Turner and Riding, he thinks the fossils could have been made by many different kinds of microbes. "These things could be absolutely anything," he told CBC News. "There's just nothing distinctive here at all."

Qing Tang, a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Hong Kong, has previously written about the lack of really old sponge fossils being an "annoying problem for paleontologists," given that they're thought to have evolved much earlier than the oldest fossils, and most modern sponges (but not horny sponges) have hard skeletons that should be easily fossilized.

Some of his research has found that some very old sponges may not have had those hard skeletons.

But he said in this case, the fossils remind him of another fossil from between 635 million and 538 million years ago that was originally thought to be a sponge. After more detailed 3D analysis, researchers decided the fossils were more likely made by microbes.

He suggested more sophisticated 3D analysis are needed to confirm Turner's discovery.

"This discovery is overall very interesting," Qing said in an email.

"It will be a big step towards a better understanding of early animal evolution if the keratose sponge interpretation is eventually confirmed, particularly given its age… However, as is denoted in the title, these structures are best called possible sponge fossils due to relatively few characters preserved."

This article, written by Emily Chung, was originally published for CBC News.