Cold a likely factor in lower butterfly count in major Canadian city

Butterfly sightings are down in Vancouver, B.C., this year, with one theory pinpointing a January cold snap as one of the culprits

For many of us, we tend to go into hiding when it is cold outside, especially during the winter.

Well, a similar weather scenario could also explain the lack of butterfly appearances in a major Canadian City on the West Coast this year.

SEE ALSO: Could climate change bring paradigm shift in biodiversity tracking?

Cited by the University of British Columbia (UBC) and published on iNaturalist –– which incorporates image recognition software online and on smartphones to help users instantly identify plants and animals observed anywhere –– roughly 400 observations of 22 butterfly species were documented in Metro Vancouver, B.C., from April to June 2024, down from about 1,000 in the same period in 2023.

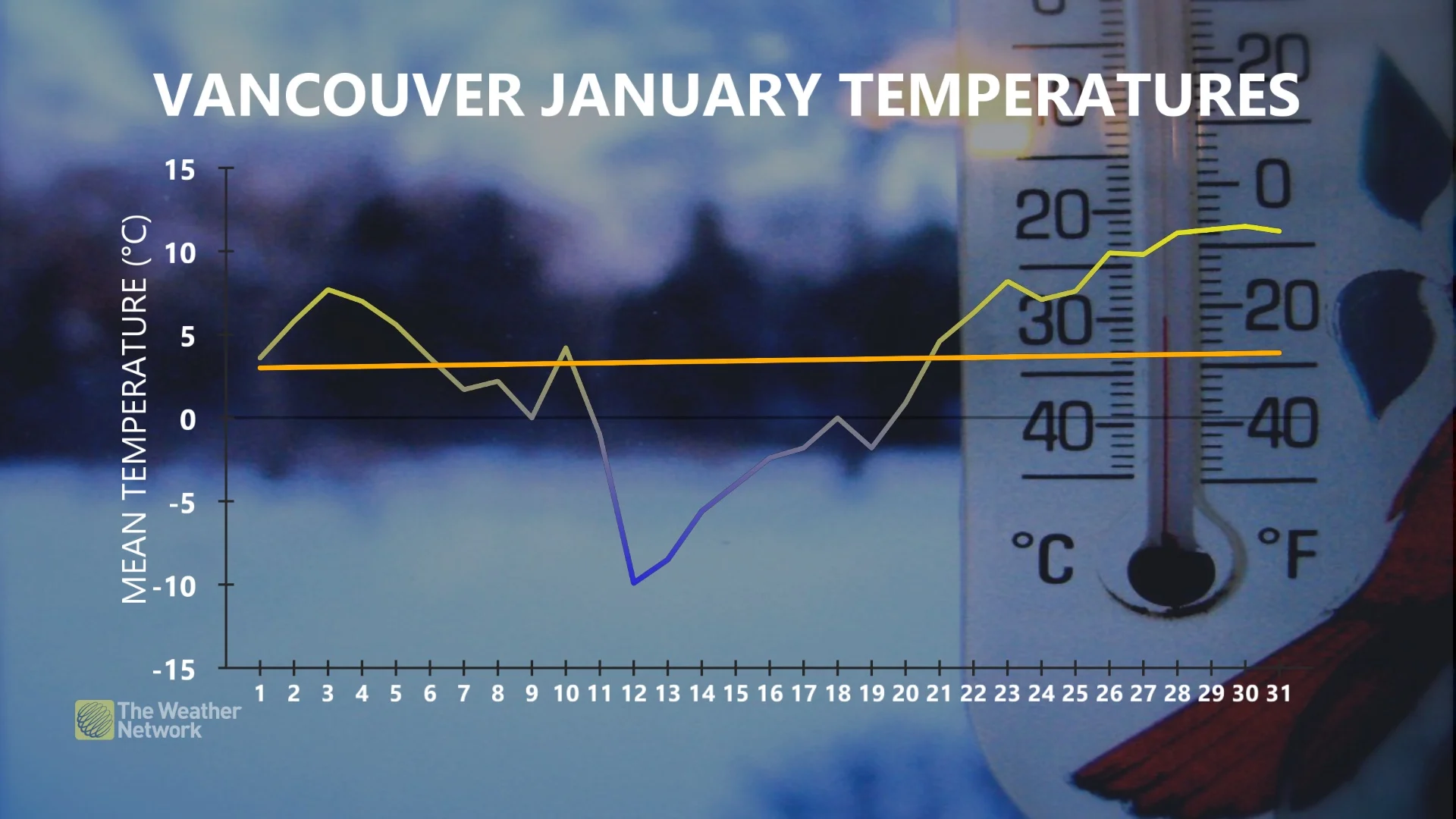

According to UBC, colder-than-normal temperatures in Vancouver in January may have been a factor.

Cabbage white butterfly. (Michelle Tseng/Submitted to The Weather Network)

"Given that butterfly numbers were low across a fairly large region of British Columbia, one theory we have is that the cold snap in early January may have killed many overwintering butterflies," said Michelle Tseng, a UBC assistant botany and zoology professor, in a response emailed to The Weather Network recently.

B.C. cold snap followed unusually warm December

An unusual outbreak of Arctic air descended over the province in early January, a stark contrast to the exceptionally mild December 2023, which set records for warm temperatures across the country.

By the end of the first week of January, a ridge of high pressure that formed in Alaska pushed frigid air all the way to B.C.'s coast, sending temperatures plummeting into the negative digits.

January 2024 temperatures in Vancouver, B.C. (The Weather Network)

Most of January was below normal in terms of temperatures, other than the very beginning and end of it. The mid-month cold period was so extreme it severely affected B.C.'s wine industry.

And, because of how quickly the temperatures dropped in Vancouver during that time, the survival of the butterflies could have been affected, Tseng said.

"There were a few days in January when the temperature plummeted very quickly over a span of 24 hours," said Tseng. "We’ve seen in laboratory studies that sometimes [indicate] it’s how quickly the temperature changes, rather than the final temperature per se, [which] affects insect survival."

(Michelle Tseng/Submitted to The Weather Network)

As an example of a quick temperature drop in the B.C. city this year, using weather station data from Vancouver International Airport (YVR), the assistant UBC professor noted that between 11 a.m. PST on Jan. 11 and 8 a.m. PST on Jan. 12, the values dropped from 3.6 C to -13.3 C –– a nearly 17-degree plunge.

There was also a wind chill of -24 at the time of the temperature hitting -13.3 C, but Tseng said researchers don't know if overwintering butterflies feel wind chills, and aren't sure of the exact temperatures the insects would have been exposed to during the plummet.

However, there could still be a connection between the cold snap and the lower butterfly count this year.

"Still, there seems to be a correlation between the regions that experienced the cold snap and the regions where we are seeing fewer butterflies this year," said Tseng.

A cabbage white butterfly rests on a flower. (Michelle Tseng/Submitted to The Weather Network)

"If I exposed insects in my lab to a 27-degree change in temperature in 21 hours, [for example], I would not expect any of them to survive."

Butterfly activity 'heavily influenced' by weather

Butterfly activity is heavily influenced by weather, she said, noting cool and wet springs are also typically associated with lower butterfly numbers.

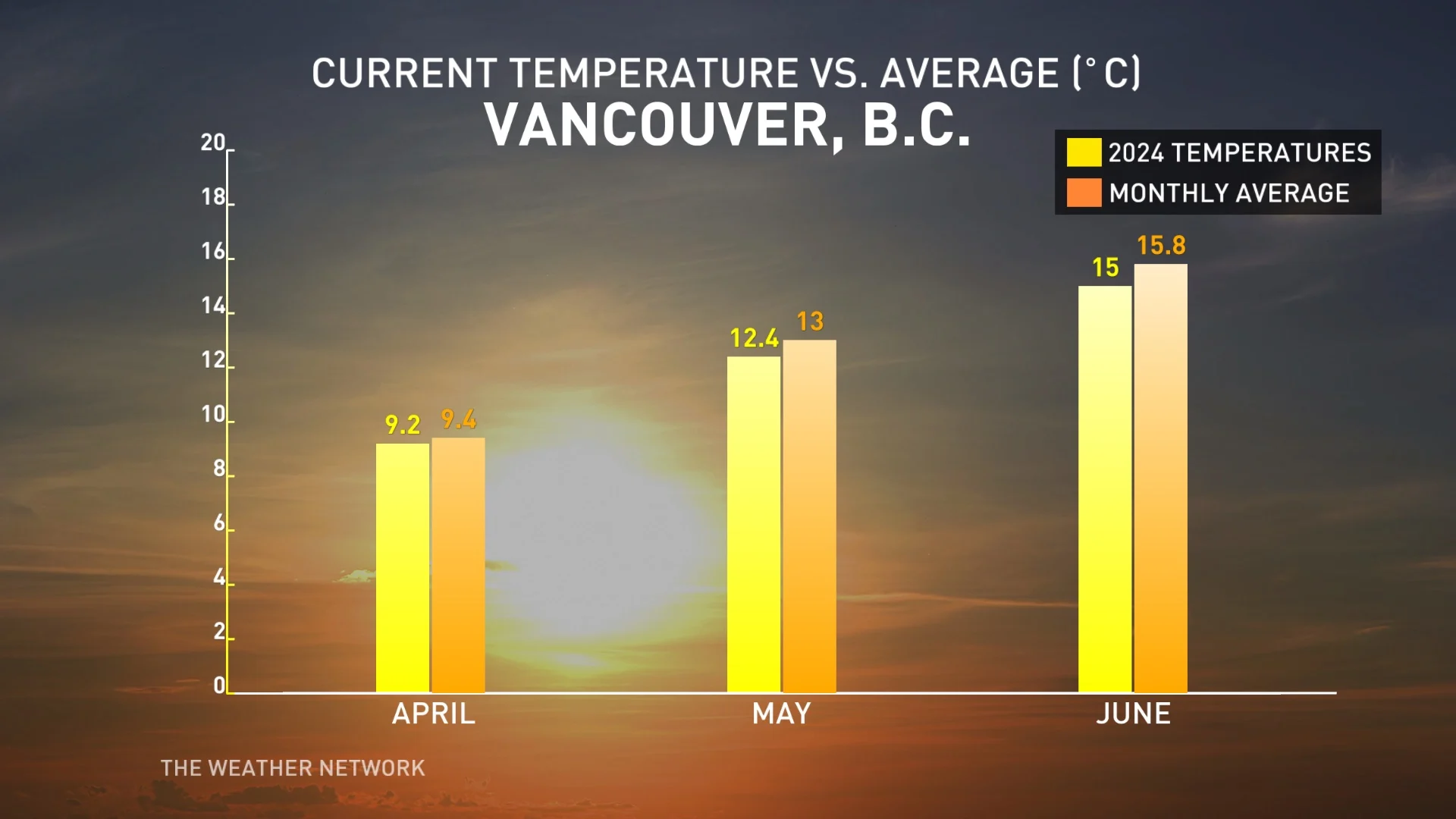

While B.C. experienced periods of below-normal temperatures and higher precipitation totals from April to June 2024 when the lower numbers of butterflies were observed, spring in Vancouver was only a little cooler than average, overall. In terms of rainfall, amounts from April-June were ordinary and seasonal.

April to June 2024 Vancouver temperatures. (The Weather Network)

Looking at those figures, Vancouver's spring this year isn't likely to be the cause for the notable decrease in butterfly sightings.

Outside of B.C., similarly cool conditions in the fall of 2023 was worrisome for the monarch butterly migration from Ontario to Mexico.

Ontario experienced record-high temperatures at the beginning of October, but a sharp polar vortex that sank down at the time caused temperatures to plummet suddenly across southern Ontario.

“Being insects (and ectotherms), they need temperatures to be 15 C and above to be able to fly any distance and find food along the way," Karin Davidson-Taylor, a butterfly expert at the Royal Botanical Gardens, told The Weather Network in a 2023 interview.

(Amanda/Submitted to The Weather Network)

"There may be a lot of roosting (multiple butterflies clustering together in trees) happening during the cold snap.”

The physical impacts on butterflies due to the heat or cold will depend on the stage of development they are in, eggs, caterpillars or adults, the types of species and location, Tseng noted.

Adult butterflies have behavioural adaptations such as shivering and basking that can help them warm up. Normally, they will do this in the morning to warm up their flight muscles so they can start flying, said Tseng. "On the flip side, if it’s very hot out, adults can seek shade or glide instead of flapping their wings."

She said eggs and some caterpillars can have adaptations that prevent them from freezing when it’s below zero, and the latter can also bask in the sun to warm up. "If it’s too hot out, even in the shade, caterpillars may not survive."

'Winners and losers' with climate change

When it comes to climate change, there are going to be "winners and losers," Tseng said, so the challenge facing ecologists is predicting which organisms will fall into each category.

(Getty Images)

"The butterfly species we worry the most about are those that already [have] very low numbers. In B.C., we have seven species of endangered butterflies," said Tseng.

"Extreme weather events are an additional stressor that might drive these species to local extinction (extirpation)."

Most ideal solution to help butterflies is also the hardest: Expert

The best solution to aid butterflies is also the most difficult, she said, which is to ensure they have access to large quantities of suitable habitat.

"For our native butterflies, their caterpillars typically eat specific species of native plants or trees. Unfortunately, in many urban areas, we have replaced native trees with introduced species and have replaced native shrubs and other plants with showy, ornamental plants," said Tseng.

(Videoblocks)

In addition to adding habitat, Tseng recommends people avoid using pesticides when possible and to grow plants that provide adult butterflies with nectar.

As well, another "very helpful" tip is to take a picture of any butterfly they see and upload the photo to iNaturalist.

"These pictures are very valuable for understanding which butterflies are thriving versus which are in decline," added Tseng.

WATCH: Monarch butterflies could die off in our lifetime, here's how to help

Thumbnail courtesy of Michelle Tseng.

With files from meteorologists at The Weather Network, and Victoria Fenn Alvarado, a video journalist at The Weather Network.

Follow Nathan Howes on X, formerly known as Twitter.