In Peru, 'marine monster' skull points to fearsome ancient predator

By Marco Aquino and Carlos Valdez

LIMA (Reuters) - Paleontologists have unearthed the skull of a ferocious marine predator, an ancient ancestor of modern-day whales, which once lived in a prehistoric ocean that covered part of what is now Peru, scientists announced on Thursday.

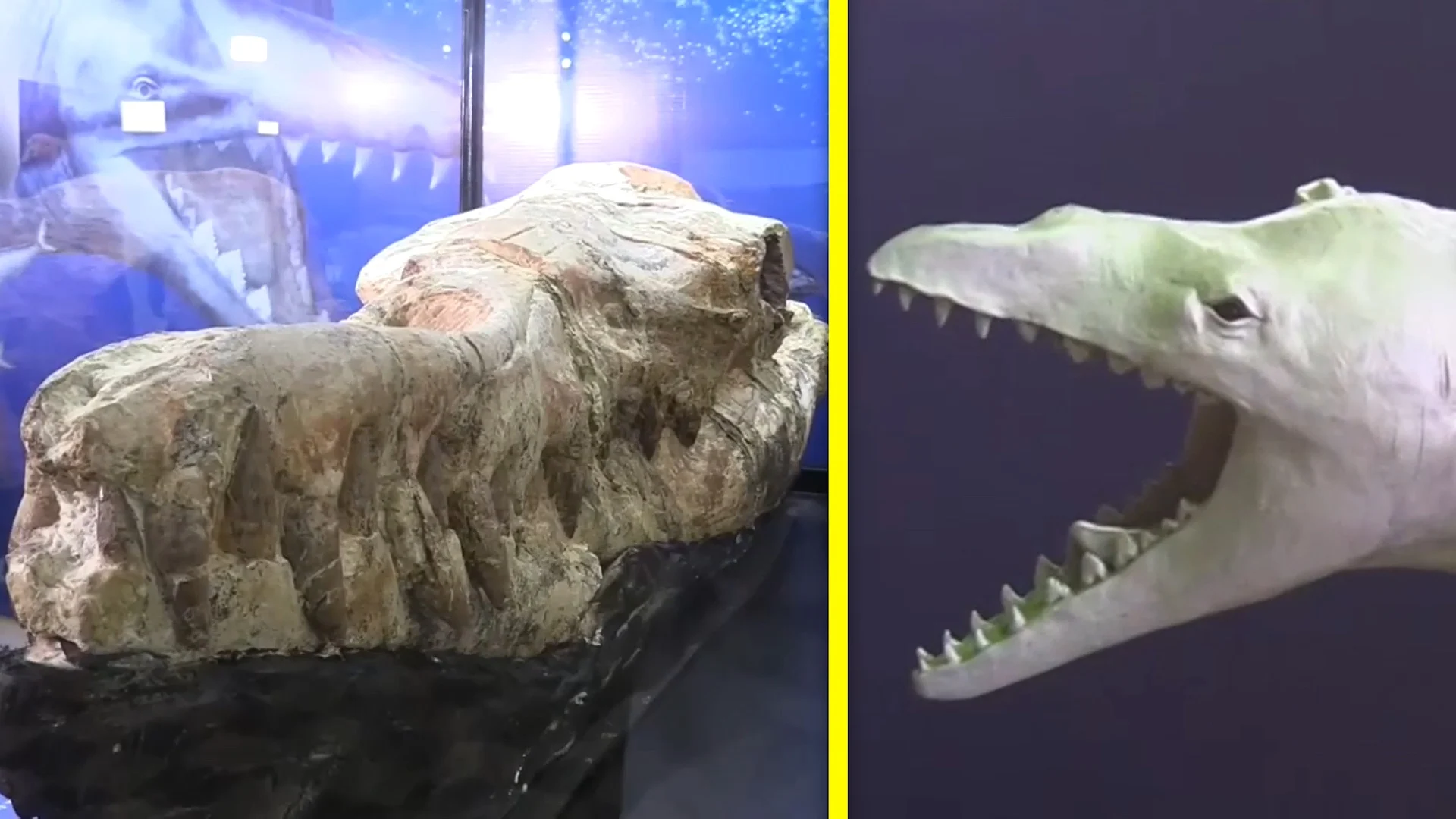

The roughly 36-million-year-old well-preserved skull was dug up intact last year from the bone-dry rocks of Peru's southern Ocucaje desert, with rows of long, pointy teeth, Rodolfo Salas, chief of paleontology at Peru's National University of San Marcos, told reporters at a news conference.

Scientists think the ancient mammal was a basilosaurus, part of the aquatic cetacean family, whose contemporary descendents include whales, dolphins and porpoises.

Basilosaurus means "king lizard," although the animal was not a reptile, though its long body might have moved like a giant snake.

A Basilosaurus whale fossil dating back 36 million years is displayed at the Museum of Natural History after its discovery in the Ocucaje desert, in Lima, Peru March 17, 2022. REUTERS/Sebastian Castaneda

The one-time top predator likely measured some 12 meters (39 feet) long, or about the height of a four-story building.

"It was a marine monster," said Salas, adding the skull, which has already been put on display at the university's museum, may belong to a new species of basilosaurus.

"When it was searching for its food, it surely did a lot of damage," added Salas.

Scientists believe the first cetaceans evolved from mammals that lived on land some 55 million years ago, about 10 million years after an asteroid struck just off what is now Mexico's Yucatan peninsula, wiping out most life on Earth, including the dinosaurs.

A Basilosaurus whale fossil dating back 36 million years is displayed at the Museum of Natural History after its discovery in the Ocucaje desert, in Lima, Peru March 17, 2022. REUTERS/Sebastian Castaneda

Salas explained that when the ancient basilosaurus died, its skull likely sunk to the bottom of the sea floor, where it was quickly buried and preserved.

"Back during this age, the conditions for fossilization were very good in Ocucaje," he said.

(Reporting by Marco Aquino and Carlos Valdez; Writing by David Alire Garcia; Editing by Karishma Singh)

Thumbnail courtesy of EFE | Reuters.