Here's why parts of the ocean off Newfoundland look like tropical Bali lately

You might have noticed the ocean's a weird colour this summer — but why? (Layna Willcott)

If you've looked out to sea lately wondering why Newfoundland brings to mind a (perhaps slightly colder) coast off the Maldives, here's the answer you're searching for.

"The reason they (the waters) look tropical is because it's a big phytoplankton bloom," said Cynthia McKenzie, a scientist with the Department of Fisheries and Oceans.

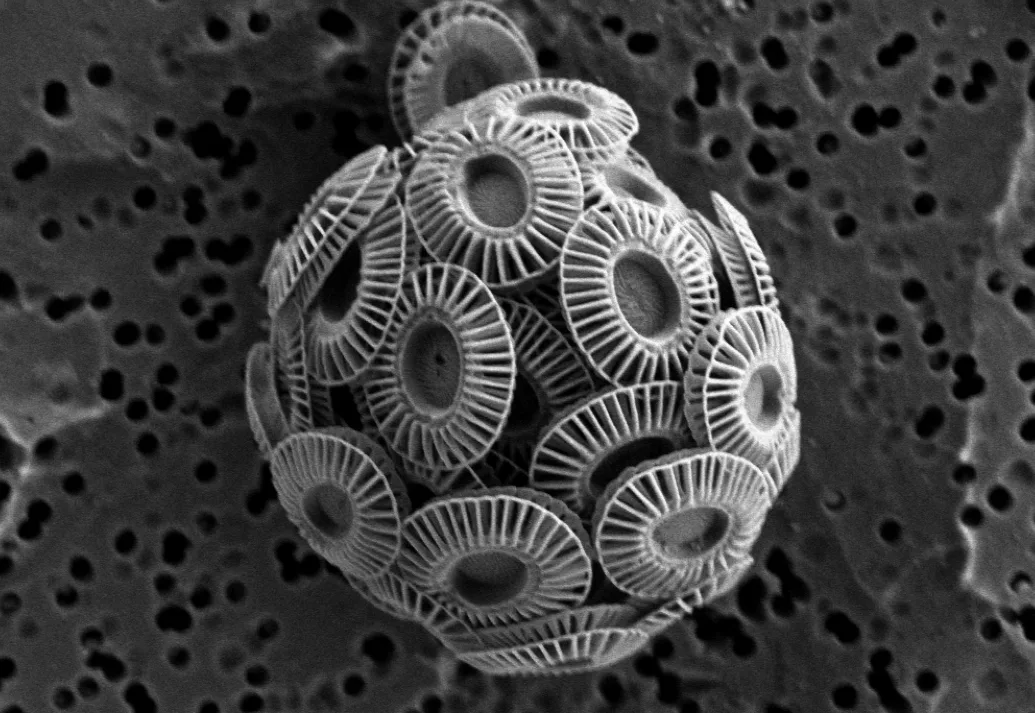

The type of plankton making up the bloom, called coccolithophores, are so tiny that all by themselves they'd be invisible to the human eye: just five microns in length, "or like, a thousandth of a sand grain," she said.

Together, however, they're making a splash in the waters off parts of Newfoundland. "There's so many of them out there, that you can actually see them from space," McKenzie explained.

The single-celled plankton — which are more like wandering plants, feeding off carbon dioxide and sunlight, than animals — are made out of calcium carbonate.

"That reflects light, and that's the reason we can actually see the turquoise colour ... it's like a chalk, and that's what these guys are made out of.

"The minute you see that ... the turquoise is what gives it away as a coccolithophore bloom."

McKenzie says the blooms pop up every so often in the waters off the southern part of the island, but it's the first time she's seen them so far north, in places like Trinity Bay and Conception Bay.

They've lasted longer this time around, too, she says.

That indicates they're happy where they are, clustered close to the shore and near the surface of the water, where the phytoplankton can pick up the most sunlight and warmth.

"That's why they show up really well on satellite images."

Even Hurricane Dorian didn't sway the little guys. McKenzie theorizes it's because shifts in the water brought more nutrients drifting in.

"So they're hanging around even more now," she said.

As for how long they'll stick around? The phytoplankton will eventually die off — but this time, thanks to favourable conditions, McKenzie thinks it could take weeks instead of days.

This article was written for the CBC.