Canada ranks high for mammal movement between protected areas: Study

Many of Canada's protected areas are adequately allowing mammals to move freely between them, according to a recent study, but the country's growing human pressures on the environment threaten their connectivity.

Despite the numerous human pressures on Canada's environment, the country is doing a pretty decent job of safeguarding its wildlife as it turns out.

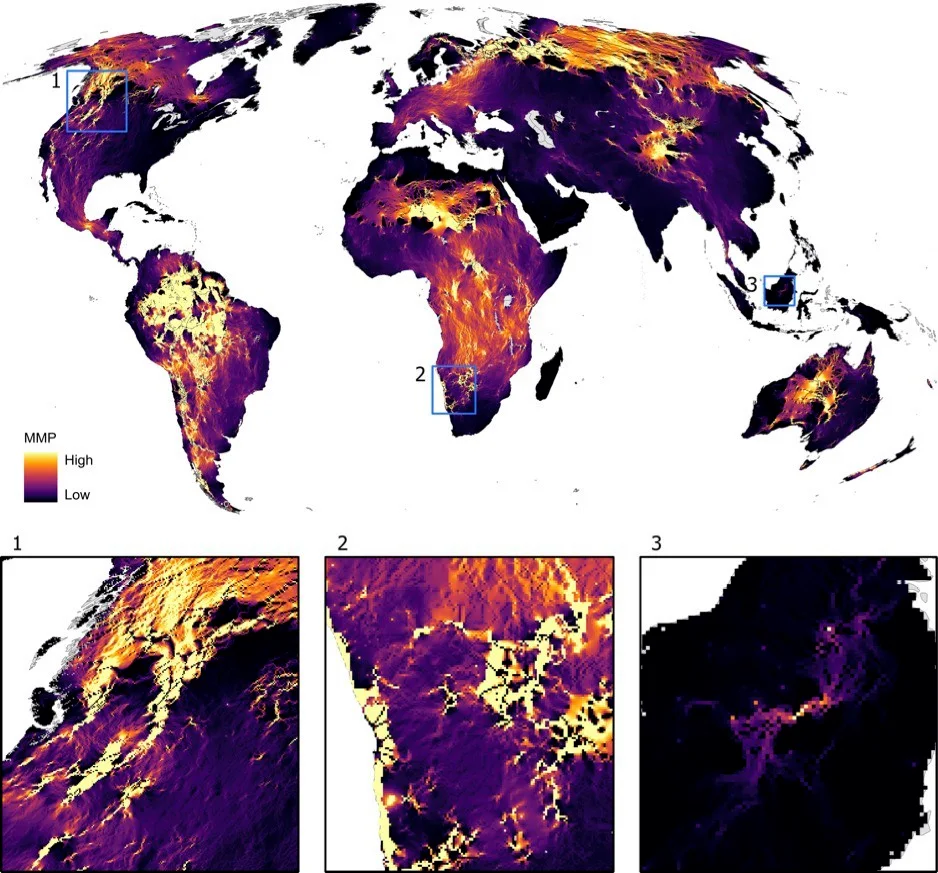

As part of a unique study from the World Wildlife Fund, and the universities of British Columbia (UBC) and Colorado Boulder, researchers created the first global map of where mammals are most likely to move between protected areas including national parks and nature reserves.

SEE ALSO: How and where to go on a safe quest to see wildlife in Canada

The results were favourable for Canada, which ranked third -- a score relative to other countries. It indicates that its protected areas are, on average, more connected for safe mammal passage than preserved zones in other countries where human use and development is much higher, according to Angela Brennan, research associate at the Institute for Resources, Environment and Sustainability at UBC.

“Because of the importance of connectivity, it's really surprising that this is the first time there has been a global analysis of functional connectivity and protected areas for moving mammals," said Brennan, in a recent interview with The Weather Network. She is also a fellow with the U.S. World Wildlife Fund.

Global mammal movement probability (MMP) between terrestrial protected areas. (Reprinted with permission from Brennan et al, Science 377:1101-1104 (2022)).

“Canada has some really amazing national parks and protected areas. Many of these are located in the northern half of the country where there are large swaths of largely intact land.”

Canada still needs improvement

However, the high ranking for Canada does not mean all of the country’s protected areas are well connected, Brennan added. Many protected areas in the southern half of the country, for example, where the majority of Canada’s human population resides, are quite disconnected compared to protected areas in the north.

The study identified increasing human pressures on the environment, such as population density, roads and nightlights, which can further restrict mammal movement and habitat connectivity.

“We need to mitigate human pressures on the environment. And there's a lot of options and opportunities to do that, and to make sure that landscapes are managed to become more permeable to moving mammals," said Brennan.

Elk moving through the landscape. (Angela Brennan/Submitted)

A few ways to reduce our footprint include retaining natural habitats within agricultural areas, removing fences, building highway overpasses or underpasses, and restoring greenways and other stepping stones between parks.

“Having connected landscapes ensures that animals can move to access food, water, and mates. And it ensures the flow of genes across the landscape, which is needed for species persistence and ecological integrity," she said.

Cutting down human footprint by half would increase the potential for mammals to move more freely between protected areas by 28 per cent, according to the study. If both the human footprint was reduced and the size of protected areas was increased, connectivity would improve even further -- by 43 per cent.

(Warren Howes/Submitted)

Data from previous study incorporated into map creation

Brennan said “a really, really cool and well-established technique” for modelling connectivity is circuit theory, which was used to predict where mammal movement globally is going to be encumbered by human pressures on the environment.

To create the worldwide map that shows the flow of mammal movement between protected areas, researchers used data from a previous study that obtained 46 species of mammals and more than 600 individuals -- showing motion dropped with increasing human pressures on the environment, she added.

A grizzly bear walking on a logging road. (Robin Naidoo/Submitted)

"With that we applied a well-established method that relates the flow of animals moving across a heterogeneous landscape to the flow of electrical current across a circuit," said Brennan. "Sounds futuristic but it's been shown to match well with both observed animal movements and gene flow."

WATCH: How wildlife corridors are crucial to connecting wild spaces across Canada

Loss of landscape connectivity has consequences: Brennan

If we lose the landscape connectivity, it could have dire environmental consequences worldwide, not just in Canada.

“We're facing a biodiversity crisis with about a million species that are faced with extinctions, and the primary driver is rapid environmental change,” said Brennan.

However, she noted there are several ways the results of the analysis can help with conservation efforts. Since the map can plot the predicted flow of mammal movement between protected areas across the globe, it can be incorporated into worldwide conservation blueprints, perhaps offering a glimpse of hope for the future.

(Klaus Joerg/Submitted)

As well, the Convention on Biological Diversitywill be held in Montreal, Que., in December. This is where governments from around the world will meet to discuss and possibly set new goals to guide actions through 2040 to protect and restore nature.

She said connectivity will be recognized at the upcoming meeting as being “critical to achieving” biodiversity conservation.

“This analysis, these results, are really important because we were able to develop a metric that can be used by nations to monitor their progress towards these global targets,” said Brennan. “This metric...it becomes really important because it can be used to monitor progress towards meeting those goals.”

WATCH: Make your outdoor space a wildlife-friendly habitat this summer

Thumbnail courtesy of Warren Howes.

Follow Nathan Howes on Twitter.