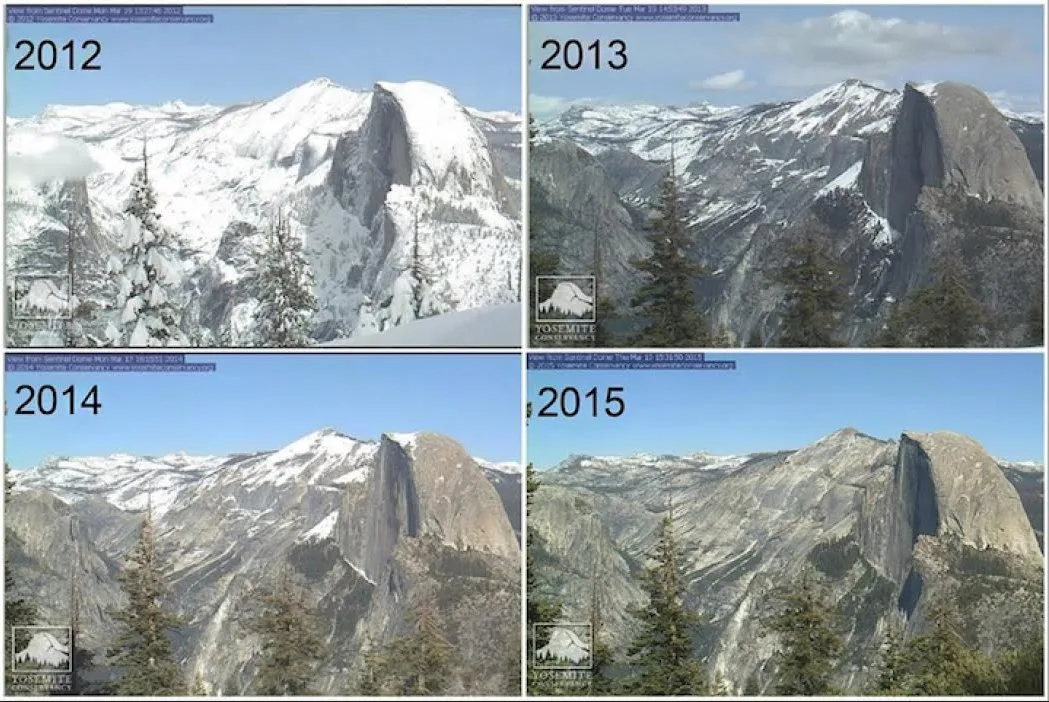

Consecutive low snow years will be more common in the future

A new study published in the journal of Geophysical Research Letters concludes that back-to-back years with a low snowpack will be six times more common across the western United States by the end of this century, a trend that will reduce water resources and stands to impact the environment and local economies.

Water from snowmelt is essential for more than 1 billion people globally. It has a direct impact on millions of lives across the western U.S. and Canada.

California, which is home to about 40 million, draws one-third of its water supply from snowmelt from the Sierra Nevada range.

public domain

Past studies have found that Earth´s warmer climate is strongly linked to a low snowpack.

Shifts in streamflow throughout the western U.S. have been driven by a decrease in winter snowfall volume and/or increased spring melt.

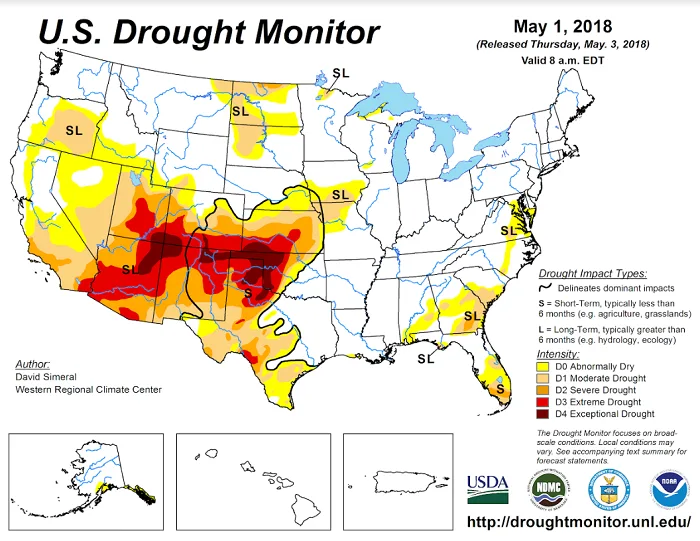

This scenario also affects snow quantity and quality for the region's many ski resorts. During a drought period last winter, water resources in several western states where just a fraction of historical values.

In January, almost all of the open resorts in New Mexico, Arizona, Colorado, Utah, Nevada and California relied heavily on man-made snow to operate.

"Every time we have a snow drought, we're delving into our water resources and the ecosystem's resources," says lead scientist Adrienne Marshall, a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Idaho College of Natural resources.

"We're drawing down on our savings without restocking the bank."

For the first time, Marshall's study has helped to establish the year-over-year variability.

Researchers analyzed projected annual changes in peak snowpack and the timing of peak snowpack. They used historical conditions from 1970-99 and projected the snowpack for 2050-79 under a rising carbon emissions future climate scenario adopted by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change.

For the simulation period 2050-79, the frequency of snow drought years with low snowpack values are expected to rise from 6.6 per cent to 42.2 per cent. The most extreme values would affect the Sierra Nevada, Cascades and northern Rockies.

The study also reveals that in the west, the period 2050-79 will see a yearly snowpack earlier, around March, rather than the current April peak.

This all means that in the years to come, ski resorts will have to adapt to different snow conditions while reservoir managers develop new adaptation strategies to account for a more inconsistent timing of the snowmelt.