Halifax scraps testing of frozen lakes for skating safety, cites climate change

The Halifax Regional Municipality has stopped testing frozen lakes and ponds to determine if the ice is thick enough for skating.

The municipality announced Wednesday that its testing program, which analyzed over 70 lakes and ponds each winter, is no longer operating.

It cited climate change as a primary reason behind the decision to stop the program, which the city described as resource intensive.

SEE ALSO: Steps to follow to ensure your survival after a fall through the ice

"Due to warmer winters, there is a smaller period of time where testing ice thickness is even possible," the city said in a statement on its website.

"For example, there was only two to three weeks this past winter where testing could take place. This resulted in one day of approved skating each year over the past few years."

The municipality acknowledged that while some residents may still wish to skate on frozen surfaces, it will be up to them to take the appropriate safety precautions.

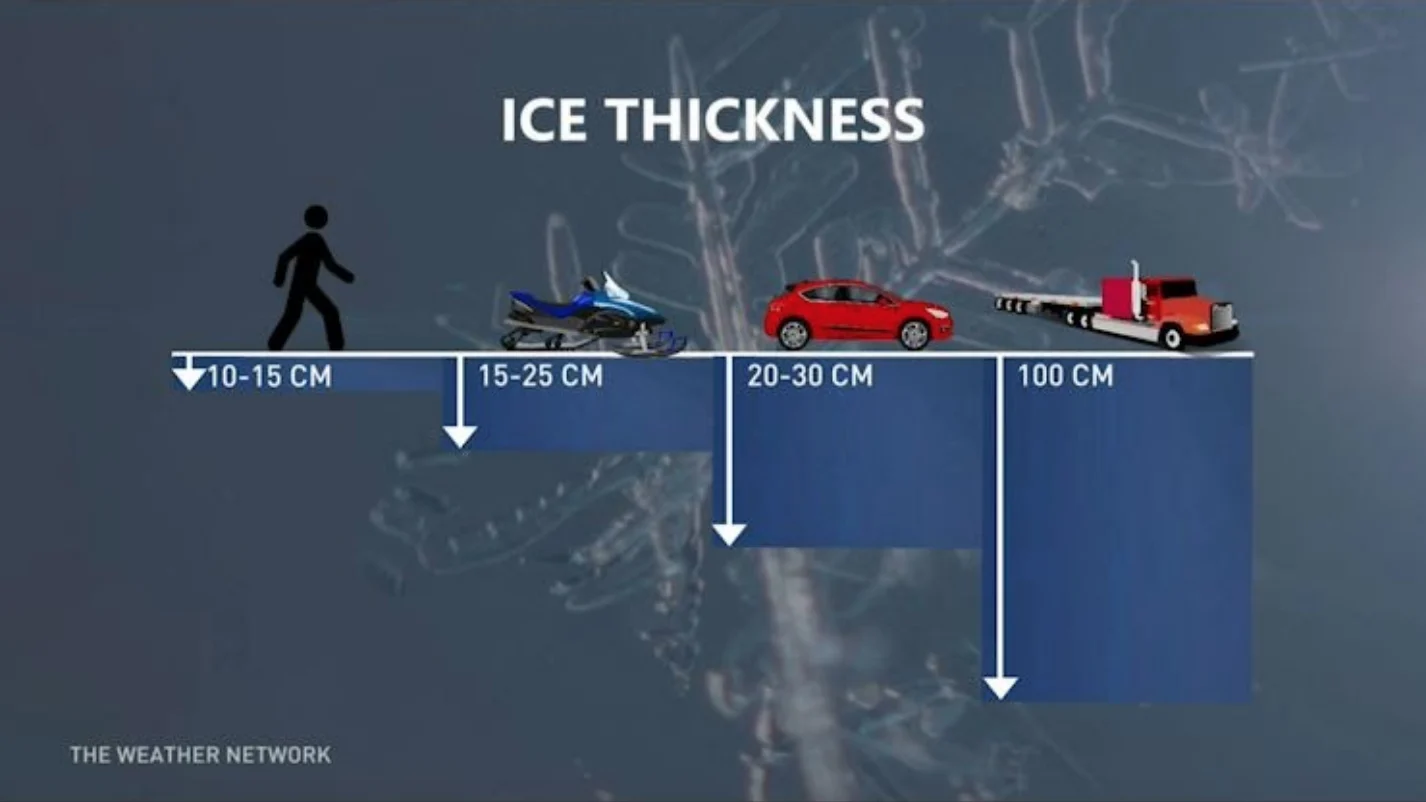

It also referred to ice safety guidelines from the Canadian Red Cross, which state that ice should be:

15 centimetres thick for walking or skating alone;

20 centimetres thick for skating parties or games;

25 centimetres thick for snowmobiles.

In his monthly newsletter, Dartmouth Centre Coun. Sam Austin noted that the program cost $24,000 per year. He said the city's Parks and Recreation Department will redirect the money toward ice and snow clearing on park paths.

"For anyone that still might be doubting the reality of climate change, consider that Dartmouth was once a place where ice was harvested, hockey may have been invented, and where the lakes were an integral part of winter recreation, even supporting horse and car races," he wrote.

"Those days are well behind us now. Winter isn't what it was."

A huge crowd of people enjoy a skate on Chocolate Lake in this archival photo from February of 1977. (Halifax Municipal Archives)

For Norma Lee MacLeod, a longtime resident of the Chocolate Lake area, the decision to stop the program is disappointing but not surprising.

She's been tracking the skating season since she moved to the neighbourhood in 1998.

"It was a normal thing to skate on the lake in the winter, and there are historic pictures of Chocolate Lake with hundreds of people out there," MacLeod said.

But lately, she said she's lucky if she gets a couple of skating days a year.

"We can see climate change right out the window," said MacLeod.

"The lake that used to be frozen for several weeks at a time, perhaps even two months at a time, is now rarely frozen thick enough to skate."

WATCH: Will an El Niño winter mean a rise in thin ice fatalities?

Thumbnail courtesy of Aly Thomson/CBC.

The story was originally written by Andrew Sampson and published for CBC News.