Large reservoir of freshwater found hidden beneath the North Atlantic

The first evidence of this reservoir dates back to the 1970s s when oil drilling sometimes brought up freshwater, but no one expected it to be this large.

Source: Getty Images

Well below the salty waters of the North Atlantic lies a huge untapped reservoir of freshwater, according to a study published in the journal Scientific Reports on June 18. Geologists have recently discovered it just off the U.S. northeast coast from New Jersey to Massachusetts. The group of scientists studying the area, led by Chloe Gustafson from Columbia University, said it this discovery was not completely unexpected, but that it is certainly surprising to find so much untouched freshwater. The first evidence of this reservoir dates back to the 1970s s when oil drilling sometimes brought up freshwater, but nobody expected it to be so large.

Gustafson's team conducted a pilot study off the coast of New Jersey and Martha's Vineyard in Massachusetts back in 2015. The initial clue came from oil companies drilling in the area, which reported finding pockets of freshwater. Rob Evans, a senior scientist of geology and geophysics at the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution in Massachusetts, spent 10 days at sea taking measurements. Evans noticed the mega aquifer while looking for groundwater deposits buried in sediments below continental shelves.

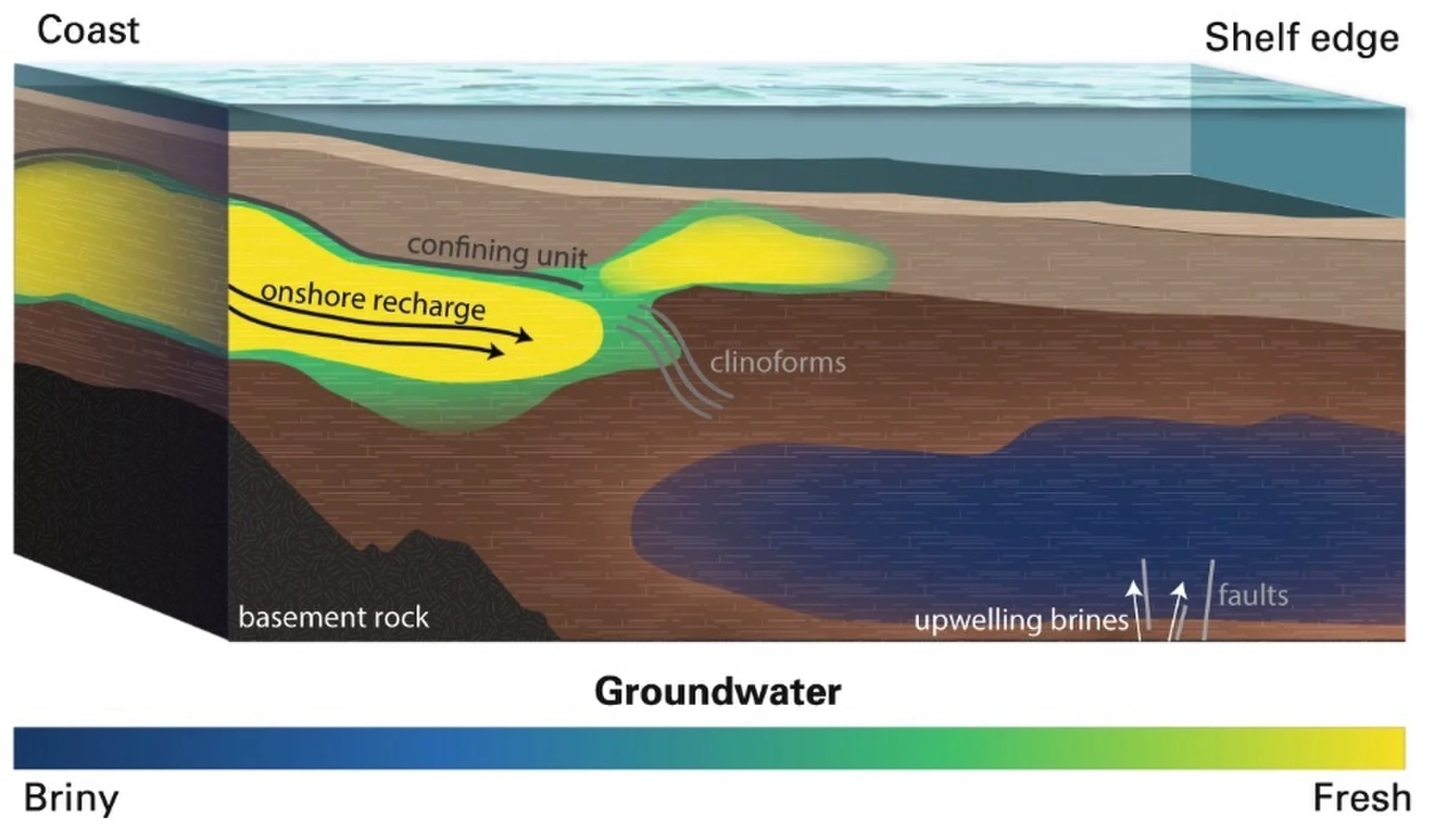

Image: The yellow hatched area shows where the giant aquifer is hiding under the Atlantic Ocean. Credit: Gustafson et al., 2019.

The exact size of the underground water swath is unknown, but it is most likely the largest of its kind, given that it extends north to south along the northeast U.S. around 350 kilometres with an approximate water volume of 2,800 cubic kilometres. The water in the reservoir is slightly salty and not exactly young, as scientists believe much of it comes from the last ice age.

To reach the aquifer, researchers dropped instruments to the seafloor and measured the electromagnetic fields below. Behind the ship carrying the sensors, a second instrument emitted artificial electromagnetic pulses and the reactions from the seafloor were measured. Since salt and freshwater conduct electromagnetic waves differently, they were able to distinguish areas of freshwater deposits. In some areas, the freshwater aquifer stretched as much as 120 kilometres away from the coast.

HOW DOES ALL THAT WATER END UP BELOW THE OCEAN?

According to the research team, the aquifer is about 20,000 to 15,000 years old, and when formed at the end of the last ice age, much of the world´s water was locked up in glaciers, and sea levels were much lower than they are today.

Image: Diagram of conceptual model showing how offshore groundwater feeds the aquifer. Credit: Gustafson et al., 2019.

With a warmer climate, experts also expect permafrost to be progressively displaced towards the northeast sector of Siberia. Moreover, the extension of frozen ground is expected to gradually fade away from the current 65% to around 40% by 2080. The de-icing of subsurface soil would also allow new species to grow and locals to harvest new crops that would otherwise never survive under the current frigid weather conditions across the region.

With temperatures rising and large masses of ice across the U.S. northeast, water washed away huge quantities of sediments, which formed river deltas on the still-exposed continental shelf. Large pockets of fresh water from the melted glaciers then got stuck in these sediment traps. Later, sea levels rose, trapping the sediment and freshwater under the ocean.

The water in this aquifer is not stagnant, with flows being fed by subterranean water running off from land. This water then goes to the sea via rising and falling tides. But somehow, it could be tapped to provide some alternative to current freshwater much needed in some communities of the northeast U.S.

Source: Scientific Reports