Canadian's work helps launch cutting-edge pollution monitoring satellite

Caroline Nowlan has spent a decade working on a machine that she's only seen once, through a window.

And that's probably all she's going to get, now that TEMPO is 35,000 kilometres above the surface of the Earth.

The Harvard–Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics researcher is a member of the team behind a new kind of pollution measuring instrument.

According to NASA, TEMPO is the first instrument to be able to measure air pollution — in real time — over all of North America.

Once it's in orbit and calibrated, it will be making hourly measurements and delivering a terabyte of data a day to researchers like Nowlan.

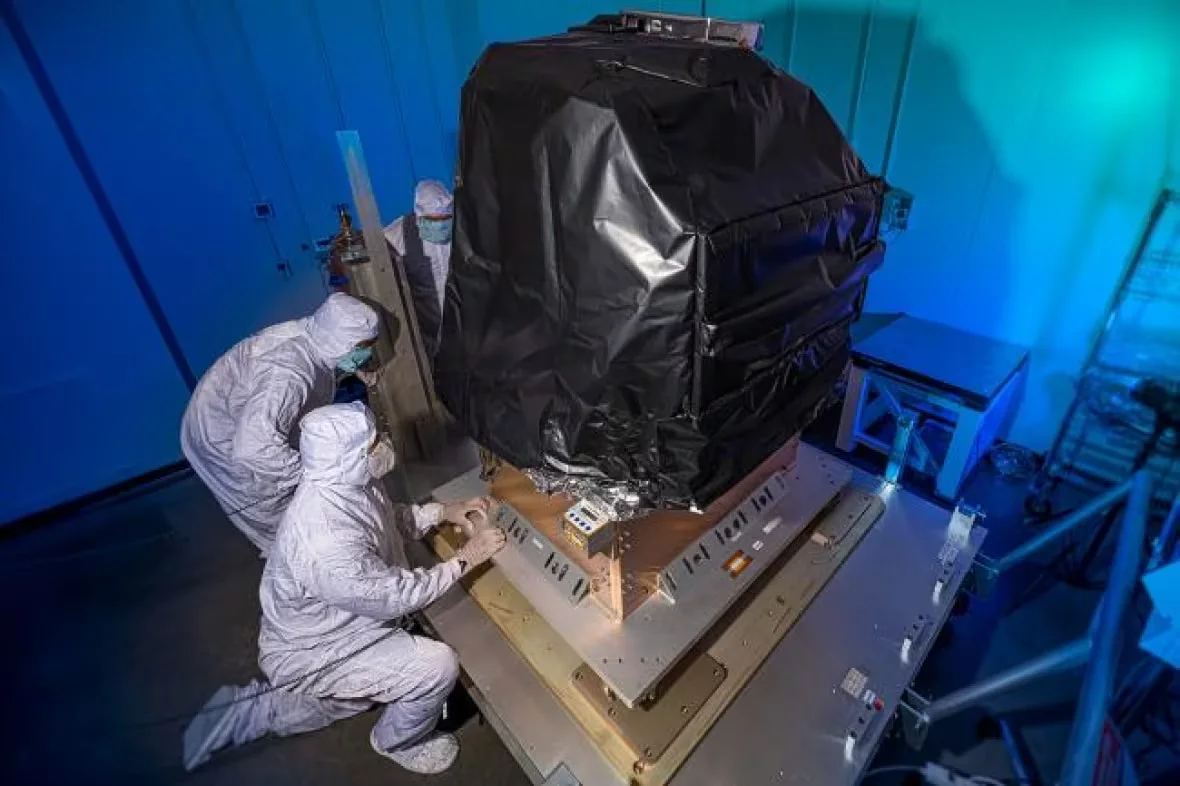

The Tropospheric Emissions: Monitoring of Pollution (TEMPO) instrument was launched on Friday, April 7 from launch pad 40 at the Cape Canaveral Space Force Station in Florida. (Walter Scriptunas/Center for Astrophysics | Harvard & Smithsonian)

"I think we're going to see a lot of things that we don't expect," said Nowlan, who will help make that raw data usable for scientists, policy makers, environmental regulators and the public.

"I think it's it's going to be really exciting to be one of the first people to see this new kind of data," she said.

Nowlan, who grew up near Saint John, said once the machine is up and running, the measurements of pollution produced by her home city's refinery and pulp mill, for example, will be accurate to the minute.

Officials can compare the levels of pollution in the morning versus the afternoon, she said. They can also evaluate how effective certain regulations are at curbing certain chemicals in the air, and deciding what needs to change if the regulations aren't working.

The measurements of ozone, nitrogen dioxide and formaldehyde, to name a few, are expected to be available online by this time next year, according to NASA.

However, it's a lot of data that may not be comprehensible to people with no research background. Nowlan said a team is also working on an app that makes the information more accessible.

How is this tech different?

People have been able to measure parts of the atmosphere from space since the 1990s. Around the earth, there are about seven spectrometers, or particulate measuring machines. Earlier technology helped scientists discover the hole in the ozone layer.

But Nowlan said a big limitation of these instruments has been their orbit. They rotate around the earth in low orbit, about 700 kilometres above the surface of the Earth, and they circle the planet 14 to 15 times a day.

This way, they go over the same location on Earth at the same local time every day.

But air pollution is different at different times of the day. Rush hour air quality, for example, is impossible to understand unless compared with a time of day when there are only a few cars on the road.

"There's a lot happening in atmospheric chemistry where different pollutants are transforming during the day and right now we're not able to capture those changes," she said.

To solve this problem, TEMPO was launched to 35,000 kilometres above the surface. At that distance, it can rotate at the same rate as Earth, so it's always pointed at the entirety of North America, and can make scans of a particular city every five to 10 minutes if needed.

Nowlan said the measurements can shed light on exactly what happens to the air during rush-hour. They can help forecast air quality changes when there's a forest fire or a volcanic eruptions, and account for pollution from industry or farming.

"We're going to be able to really get down to a high resolution of time and space that we've never been able to do before."

She said Environment and Climate Change Canada will be part of TEMPO's setup this winter. Scientists will measure Toronto's air quality on the ground, and send it to the TEMPO team.

"We'll be collaborating with them, using their data to … validate our satellite measurements," she said. "To make sure our measurements make sense basically. And then they'll be using the satellite data to understand their measurements as well."

Thumbnail image courtesy of NOAA.

This article, written by Hadeel Ibrahim, was originally published by CBC News on April 22, 2023.