Earth's core confirmed to have 'reversed' its spin. So what does this mean?

The solid metal core of Earth does not rotate perfectly in time with the outer layers of the planet, and new research confirms that it has now reversed direction.

Seismic waves passing through the Earth have revealed that the inner core of our planet is now rotating out-of-sync with the layers above it.

Update: As reported below, research from January 2023 indicated that the solid metal core of Earth might have reversed its spin, as part of a decades-long pattern of slowing down and speeding up. New research published in June 2024, from an international team of scientists, has now confirmed these findings.

"We've been arguing about this for 20 years, and I think this nails it. I think we've ended the debate on whether the inner core moves, and what's been its pattern for the last couple of decades," Dr. John Vidale, a Dean's Professor of Earth Sciences at the University of Southern California's Dornsife College of Letters, Arts and Sciences, told CNN.

The original story continues below...

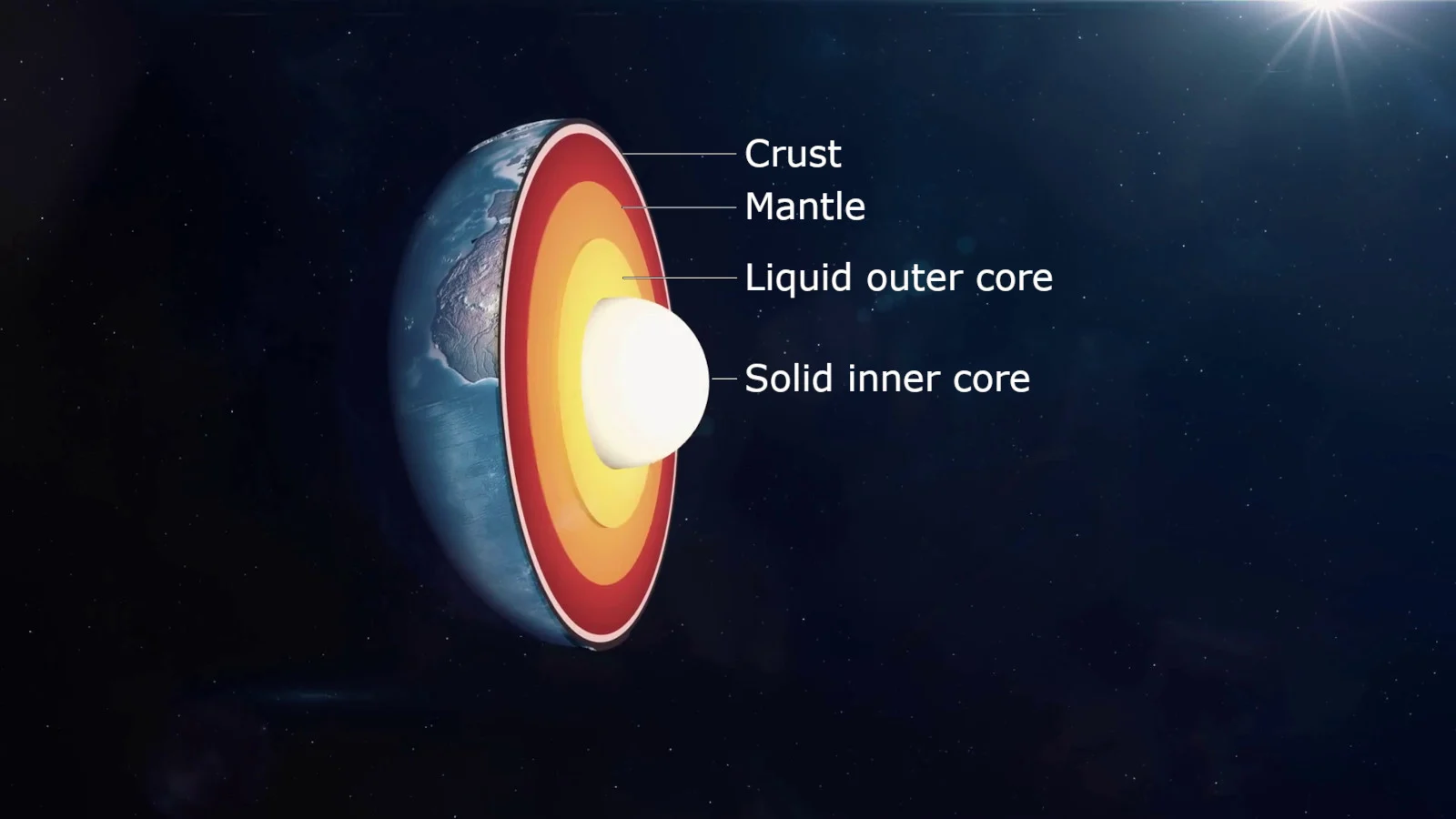

At the centre of our planet is a solid mass of nickel and iron, crushed down by gravity into a sphere roughly 2,400 kilometres wide. This solid core is surrounded by an outer layer of liquid iron and nickel, which generates Earth's protective geomagnetic field, and beyond that are the solid layers of the mantle and the crust.

This diagram shows the different layers of Earth's interior — the solid iron-nickel inner core, the molten liquid iron-nickel outer core, the layers of the mantle, and the crust. Credit: Storyblocks/SpaceStockFootage/Scott Sutherland

We know that the interior of Earth is arranged in this way due to decades of study by Earth scientists. They did so by examining the behaviour and timing of seismic waves travelling through the planet in the wake of earthquakes. While most seismic waves stop at the outer core, as they are absorbed by the liquid metal, waves from particularly powerful earthquakes can penetrate right through to the solid inner core and back out.

By carefully selecting specific seismic waves, scientists can focus on studying different properties of the inner core. Repeating earthquakes — those that occur in the same location at different times — are particularly useful for this. Since the seismic waves originate from the exact same location, they should travel along exact same paths and thus have the exact same shape when they're recorded by seismographs. If there's any difference, it's because something inside the Earth changed.

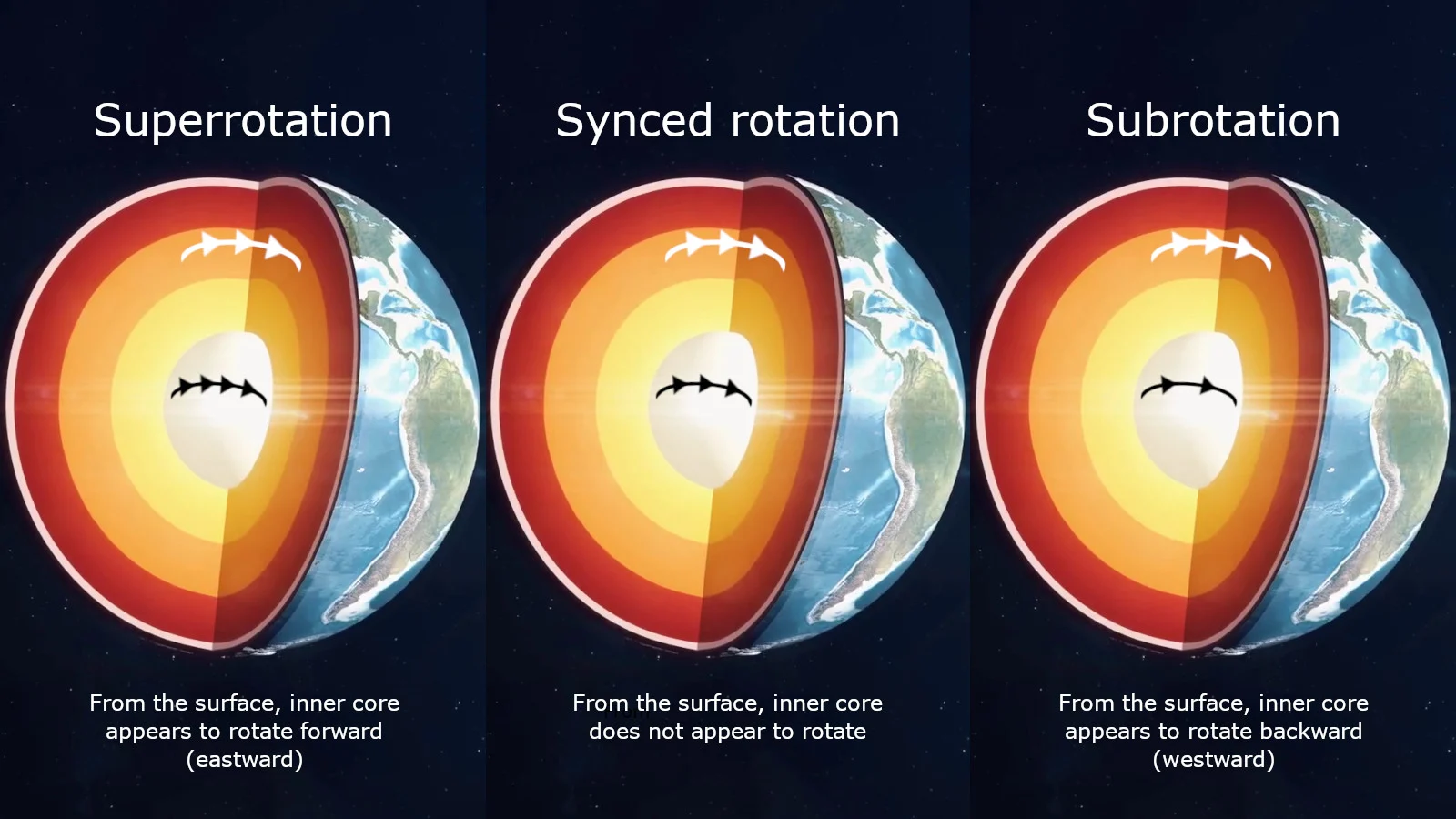

Seismic waves from powerful repeating earthquakes do show up differently at different times. The best interpretation of this is that the rotation of the core is changing over time, relative to the rotation of the mantle. That is... the core is always rotating in the same direction that the entire planet rotates (eastward), but sometimes it rotates faster than the outer layers, other times it rotates slower, and there are times when the rotations match up.

To someone standing in one spot on Earth's surface, these three states can appear, respectively, as though the core is spinning forwards, backwards, or that the spin has stopped.

This cut-away diagram of Earth's interior demonstrates the different rates of rotation of the inner core relative to the mantle and crust, and how those rotations appear to someone on the planet's surface. Credit: Storyblocks/SpaceStockFootage/Scott Sutherland

READ MORE: Earth just had its shortest day in over 60 years

So, what's this all about?

A new study, published this week in the journal Nature Geoscience, examines several decades worth of data, looking for patterns in the inner core's rotation. Researchers Yi Yang and Xiaodong Song, from SinoProbe Lab at Peking University, in Beijing, China, searched through data from 1964 to 2021 to find repeating earthquakes strong enough to produce seismic waves that could penetrate through the inner core.

Their results show that the inner core stopped spinning, relative to the mantle, from around 2009 to 2020. Since 2020, it now appears to be spinning backward. A similar pause in the rotation of the core was found in the late 1960s and early 1970s.

This graph from the research paper shows the change in the rate of core rotation since 1964 (purple and blue), along with an inverted plot of the changes in the length of a day on Earth over that same time period (gray). Credit: 2023, Yang, Y. et al/Nature Geoscience

As shown in the graph above, the changes in the rate of rotation of the inner core appear to match up with the pattern of variations in the length of day (LOD) on Earth from the past 60 years or so. Note that the graph shows the LOD variations flipped upside down, thus the more superrotation of the core, the shorter the length of day, and the more subrotation, the longer the length of day. The data is shown in this way to better line up the curves.

According to Yang and Song, variations in the length of day and Earth's geomagnetic field follow a pattern roughly six to seven decades long. With the variations in the rotation of the inner core revealed here, this means that it could also have a six to seven decade oscillation. However, they admit that since the full data record only covers a period of 56 years, they don't have enough information yet to confirm that longer oscillation.

This isn't the first research to show this kind of oscillation for the rotation of Earth's core.

In 1996, a paper by Song and Paul Richards showed the first observational evidence that the core could rotate at a different rate than the rest of the planet. Although it sparked some debate at the time, they went on to independently confirm this discovery in the years ahead.

A study published in June 2022 examined seismic data from nuclear bomb tests to closely track how the inner core rotation changed from 1969 to 1974. Their results show that the core was subrotating from 1969-1971, and superrotating from 1971-1974, the exact transition revealed in the graph above. However, the researchers note a roughly six-year cycle to the oscillation, rather than 60-year.

No need to worry

While this might seem like the plot of a sci-fi disaster movie, the change in rotation of Earth's inner core is nothing to worry about.

The core will never stop spinning, as long as we're travelling around the Sun. Plus, any talk of the core spinning backwards is only when you look at all this from the perspective of standing in one location on the surface of the planet.

The worst that can happen is that we see the length of our day increase by a tiny amount.

See, the Earth takes around 86,400 seconds to rotate on its axis once. As shown in the researchers' graph, the variation in the core's rotation ranges from two-tenths of a second slower to two-tenths of a second faster — about 0.00023 per cent of the total. The change in length of day that appears to be associated with that rotation change is, at most, around a millisecond.

To us, these are changes that we'd never notice. To the researchers, though, they're big, and they will help them to figure out even more about how our planet behaves.