Giant Antarctic ozone hole grows 2.5 times bigger than Canada

European scientists recently announced that the annual hole in the ozone layer over Antarctica reached near-record extent in September

Scientists recently discovered one of the largest holes ever observed in the ozone layer high above Antarctica.

The gap in this critical protective layer in the atmosphere grew to more than 26,000,000 square kilometres in size by the middle of September—more than 2.5 times larger than all of Canada.

Earth’s ozone layer experiences natural fluctuations in thickness with the seasons, though this year’s near-historic void likely resulted from the confluence of multiple factors.

DON'T MISS: The new age of space exploration could damage the ozone layer

Near-record ozone hole grows over Antarctica in September

The stratospheric ozone layer—which forms between about 20 and 40 kilometres above the surface—naturally grows and ebbs over Antarctica as the seasons change.

Colder temperatures allow ozone levels to wane in the late winter and early spring, which leads to its lowest extent over Antarctica in September and October.

‘Holes’ in the ozone layer aren’t ozone-less holes in the literal sense. The gas is still present in these relative voids, but in concentrations low enough that ozone levels are significantly below normal.

Satellite data gathered by the Copernicus Atmosphere Monitoring Service (CAMS) revealed unusual behaviour in the ozone layer as early as August.

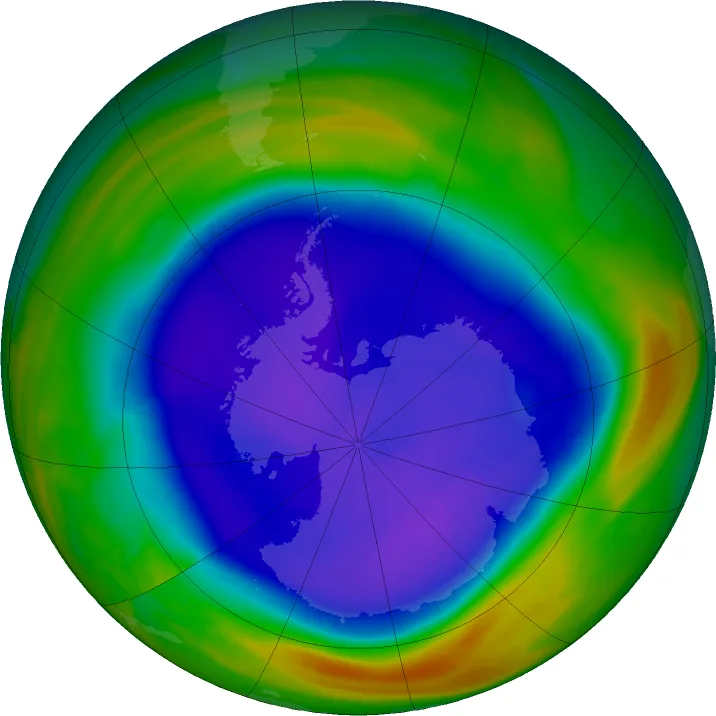

False-color view of total ozone over the Antarctic pole on September 16, 2023. The purple and blue colors are where there is the least ozone, and the yellows and reds are where there is more ozone. (NASA Ozone Watch)

The European organization announced at the end of August that the layer’s thinning began much earlier and much faster than usual as the southern hemisphere’s winter drew to a close, growing into one of the largest holes on record in the month of August.

Conditions allowed the ozone hole to continue growing at a rapid pace heading into September, reaching a near-record extent of more than 26 million square kilometres by the middle of the month.

For context, Canada is the second-largest country in the world with a total area just shy of 10 million square kilometres, making this hole about 2.6 times larger than the entire country.

Immense hole appears despite decades of ozone-friendly progress

The ozone layer dominated public environmental consciousness in the 1970s and 1980s as scientists implored companies and countries alike to curtail the use of ozone-depleting substances like chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs), a chemical compound frequently used in refrigeration and aerosol sprays.

Studies concluded that ozone-depleting substances led to a rapid degradation of this critical atmospheric component, potentially creating significant health effects for plants and animals.

Global efforts to ban CFCs culminated in the Montreal Protocol of 1987, a milestone declaration on the use of these hazardous chemicals that was unanimously ratified by all U.N. participant countries.

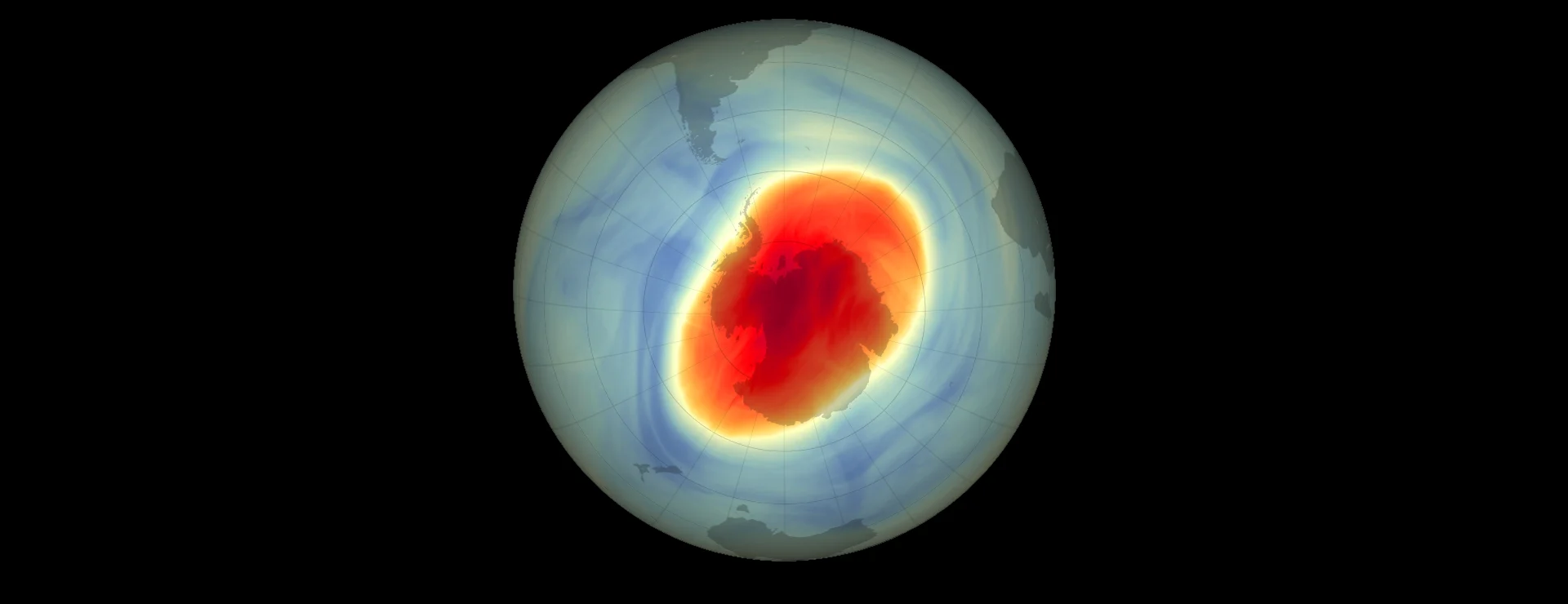

WATCH: NASA illustrates the giant 2023 ozone hole over Antarctica

DON'T MISS: Ozone layer crossed a significant milestone towards recovery in 2022

The use of substances like CFCs declined after decades of significant effort, a change that had a measurable effect on the ozone layer’s overall health.

“Since the mid-1990s, global ozone levels have become relatively stable,” NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center reported in an article published in June 2015.

The NASA article continued: “In fact, because of the Montreal Protocol, model simulations suggest the size of the hole should return to its pre-1980 levels by about 2075.”

Temperature changes and a volcanic eruption may be to blame

If conditions have markedly improved since the global community began working to curb damage to the ozone layer, then why have we seen such a notable decline in the layer so far this year?

While it’s still too early to draw concrete conclusions on this year’s accelerated loss of ozone over Antarctica, dominant weather patterns over the continent this winter likely played a role in enhancing the phenomenon.

RELATED: Tonga volcano eruption was so violent it blew ash halfway to space

A satellite image of the Hunga Tonga-Hunga Ha'apai volcanic eruption on January 15, 2022. (Japan Meteorological Agency)

A mammoth volcanic eruption in 2022 could have also played a role in this oddity. The Hunga Tonga-Hunga Ha'apai volcano erupted deep beneath the Pacific Ocean on January 15, 2022, in one of the most powerful volcanic eruptions recorded during the modern technological age.

The 2022 eruption sent a measurable shockwave around the world several times over, and it was loud enough to be heard in parts of Canada. The volcano also spewed a tremendous amount of ash and water vapour dozens of kilometres high into the atmosphere.

Hunga-Tonga “injected unprecedented amounts of water vapor into the stratosphere,” CAMS said in its August statement about the ozone layer.

The sudden infusion of millions of tons of water vapour into the atmosphere has had far-reaching consequences around the globe. This surplus of moisture may have influenced weather patterns over Antarctica in such a way that it created favourable conditions for ozone-depleting substances to react with the ozone layer and accelerate its thinning—though scientists say more research is needed to determine any connections.

Why ozone matters

Ozone is a naturally occurring gas that forms when the Sun’s ultraviolet rays react with O₂, molecular oxygen, adding one extra oxygen atom to this life-giving compound to turn it into O₃, volatile ozone gas.

A thick layer of ozone more than a dozen kilometres above Earth’s surface absorbs most of the Sun’s harmful ultraviolet radiation before it can reach the ground.

RELATED: Three scientists found a hole in the ozone layer, prompting a global treaty

This protection goes a long way toward helping humans avoid health effects like skin cancer and cataracts, and it helps plants avoid developing deadly ailments.

While it can protect us from up high, harmful ultraviolet rays interacting with pollution can create near-surface ozone, as well, leading to city-choking smog that carries its own set of health hazards.

Header image courtesy of NASA.