Solargraphy: The art, science, and chaos of capturing the Sun's path in the sky

This unique form of photography allows us to see why our seasons change throughout the year.

As Earth moves through its orbit each year, the planet's tilt causes our perspective on the Sun to change. Over time, its path gets higher in the sky leading up to the summer solstice and then it gets lower in the sky until the winter solstice.

We experience this change through the four seasons. However, we seldom, if ever, truly see it happen in our day-to-day lives.

There is a way, though, through a special form of photography known as solargraphy.

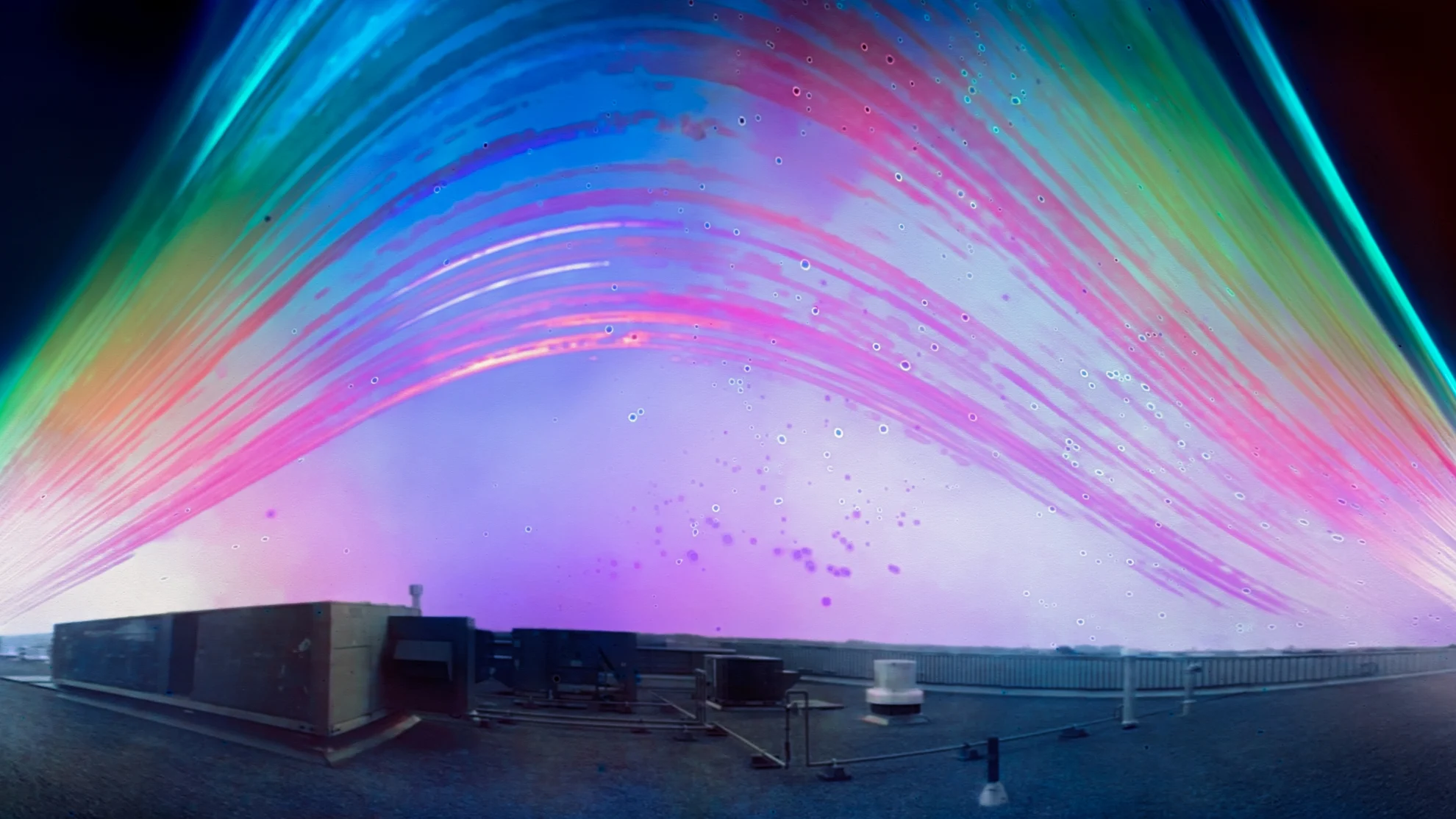

This solargraph was captured from the roof of The Weather Network between June 21 and December 21, 2023. Credit: Bret Culp

To learn more about this, I spoke with Bret Culp, a Fine Art Photographer and Visual Effects Supervisor who has worked in the television and movie industry for over 30 years. If you've watched the hit Amazon Prime science fiction series The Expanse or the Netflix horror series The Fall of the House of Usher, you've already seen some of his professional work.

Culp is also an avid photographer who seeks to capture the "impermanence" of the natural world. His photographs have been featured in art shows and galleries, internationally, and he has won over a dozen awards for his work.

For at least the past decade, Culp has also been setting up solargraph cameras, mostly in the Toronto area and along the shores of Georgian Bay, to capture the day-to-day track of the Sun across the sky.

A solargraph camera is the most basic kind of camera you can use. A piece of black and white photographic paper is sealed inside a cylinder opposite a tiny pin hole drilled into the side. The camera is then left in a safe place where it will be undisturbed for days, weeks, or even months at a time.

Now, the length of time the camera is left to record is completely up to the photographer (solargrapher?). You can record just one day — something that would be very cool to capture during a solar eclipse. Leaving the camera for an entire season is also great, but according to Culp, solstice to solstice is really the ideal period of time.

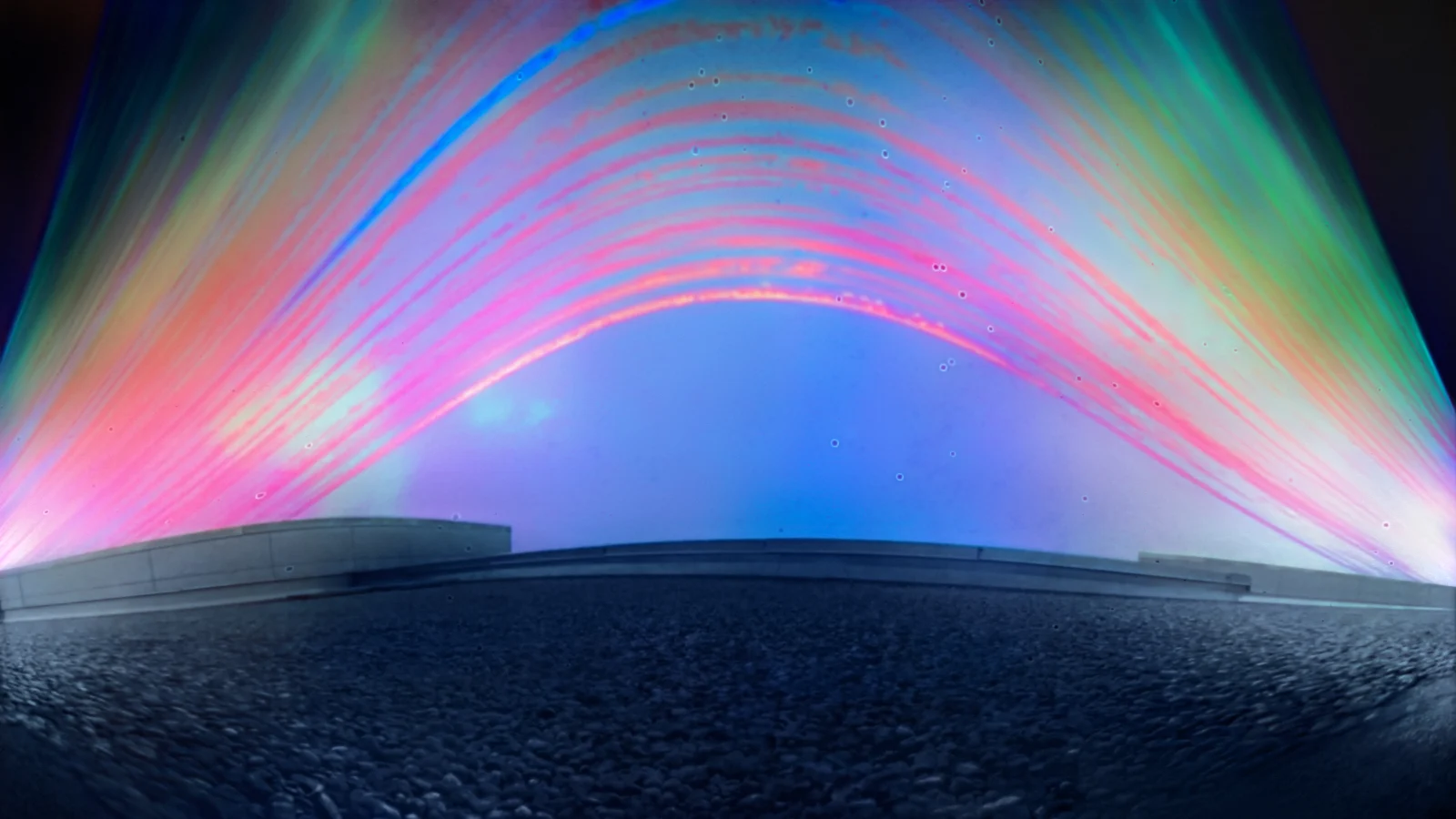

These three solargraph cameras were installed on the roof of The Weather Network in Oakville, ON, between June 21 and December 21, 2023. Painted black inside and out to reduce reflections, these cameras were positioned facing south to capture the Sun crossing the sky. Note that due to the appearance of these cameras, leaving them in a public place may result in them being taken or destroyed. Choose your location wisely! Credit: Scott Sutherland

For as long as the camera is in place, whenever the Sun is shining, sunlight will focus through the pin hole to burn a bright line of exposure onto the photographic paper. Due to the motion of Earth along its orbit, the Sun's path changes by roughly 1 degree each day. Thus, a distinct line of exposure is traced across the image for each day the camera records, which will be broken only by clouds obscuring the sky. While a completely overcast day will not show up at all, a partly cloudy day will produce a broken line of exposure.

Thus, as the photographic paper records the passage of the Sun across the sky each day, it is also capturing the change in the angle of the Sun that occurs due to the tilt of Earth's axis. As an added bonus, the image will also contain a record of the basic sky conditions that occurred above the camera's location each day.

That makes each solargraph a unique combination of art and science, with an added flare of colour that results from the extreme overexposure of the chemical photo paper, the weather conditions (heat, humidity, precipitation), and the effects of the natural environment the camera is in (dirt, mold, insects).

"I like to say that solargraphy is 'part art, part science, and part chaos'," Culp said.

The suntracks of this solargraph reveal the sky conditions over Oakville, ON, between summer solstice and winter solstice in 2023. The varying colours are a result of the photographic paper's overexposure to bright light, reflected light from the rooftop environment, and the weather conditions that occurred during that time. Credit: Bret Culp

As for how the final image is processed, a solargraph cannot be developed using normal photographic methods.

"Because it's such an extreme overexposure, you don't develop it. Otherwise the image would go completely black," Culp said. Instead, the light-sensitive photo paper is removed from the cylinder and immediately scanned into a computer using a high-quality flatbed scanner.

"As you're scanning it, you're destroying it," Culp explained, as the bright light of the scanner will completely overexpose the entire surface of the photo paper. "So, you get one shot at this."

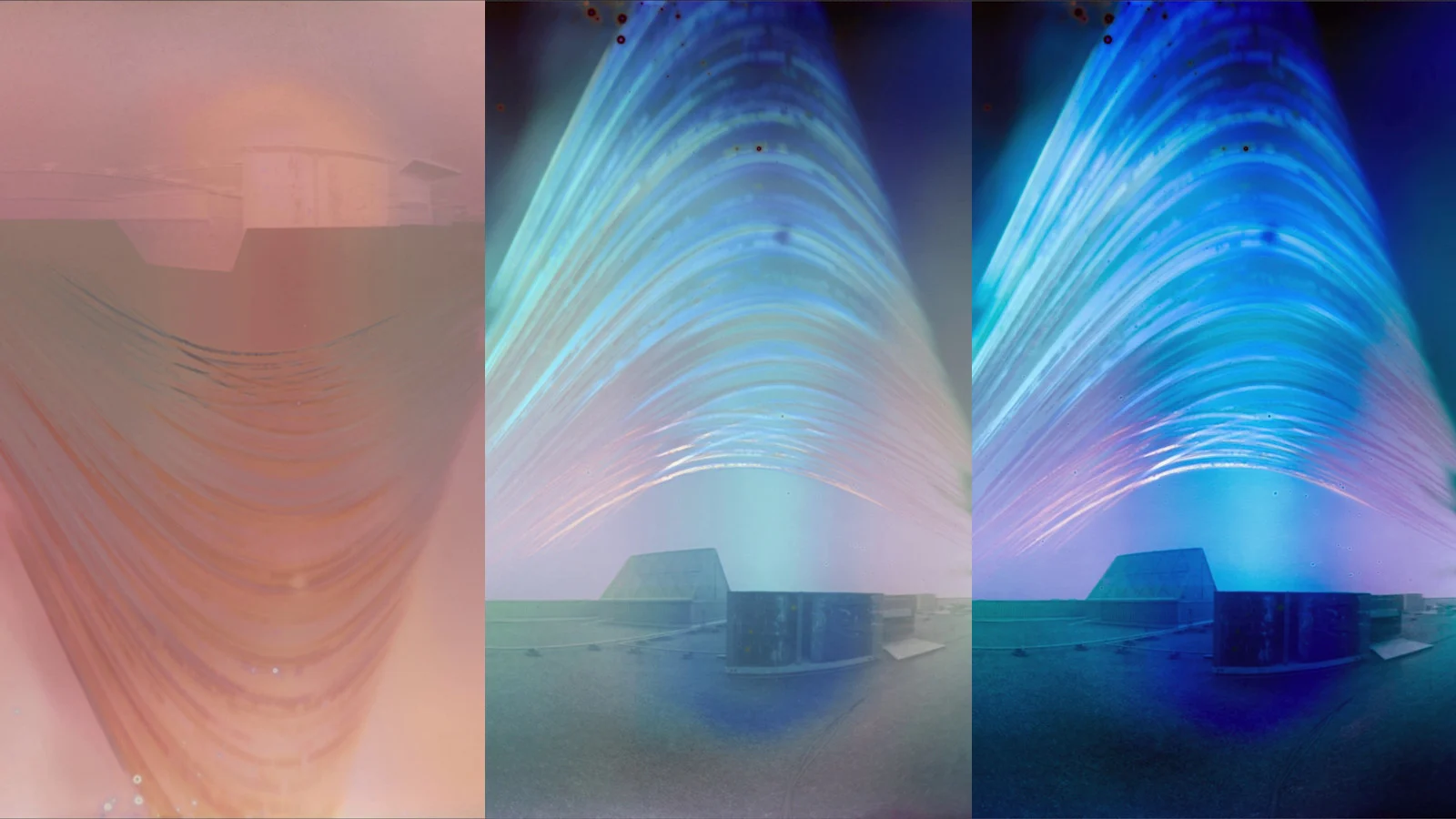

This image shows just three stages of solargraph processing, from initial scan to final image. Credit: Bret Culp

As shown above, due to the way pinhole cameras function, the resulting scan will show a flipped negative image of the camera's field of view.

From there, image processing software can be used to flip the picture vertically. The colours are then inverted from negative to positive, and the photographer can change the brightness and contrast, reduce any 'noise' in the image, and even coax out differences in the colours brought about by chemical reactions in the photo paper.

This results in a final picture that is not only unique based upon the amount of time the camera captured, the sky conditions that occurred during that time, and the colours, but also the photographer's personal taste.

For more examples of Culp's solargraphy, check out his website.