Heat, hurricanes, haboobs—deserts are a hotbed of extreme weather

The clear skies and intense sunshine that bake deserts for most of the year often give way to some of the wildest conditions nature can produce

The world’s hot deserts are some of the most inhospitable places on the planet during the summer months.

Despite the hazards, millions of travellers brave these brutal conditions every year and hop flights to party in Las Vegas, tour the pyramids of Giza, and take in the vibrant growth of the United Arab Emirates on the Persian Gulf.

But it’s not just clear skies and searing sunshine for as far as the eye can see.

Between the muggiest heat you’ll ever encounter, ferocious hurricanes, sudden flash floods, and dust storms that blot out the sun, deserts are susceptible to extreme conditions that make more temperate places seem docile by comparison.

DON'T MISS: Why extreme heat is one of the world’s deadliest weather disasters

Monsoons trigger mammoth flash floods

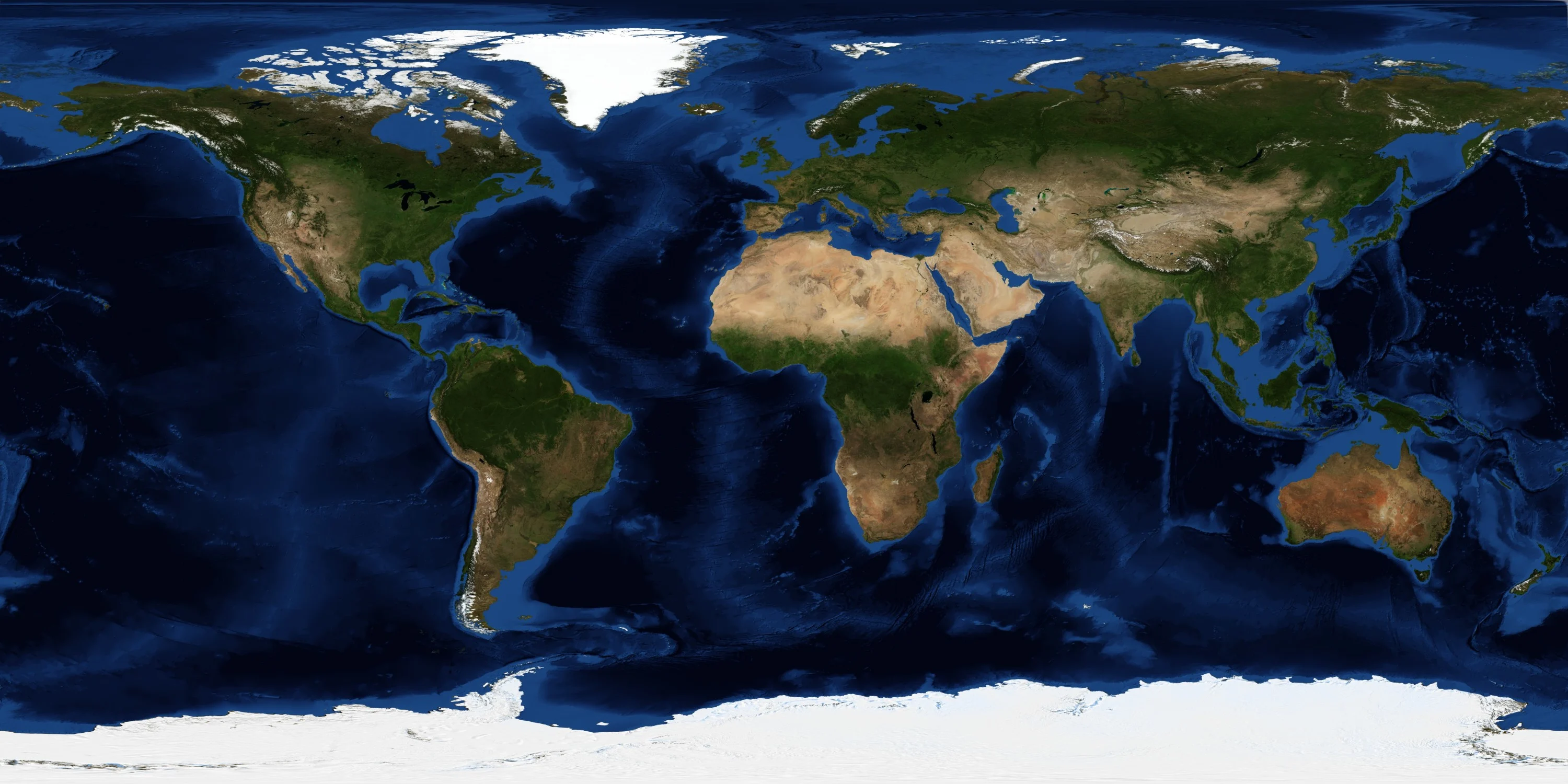

If you’ve ever gazed at a satellite image of our blue marble, you’ve probably noticed that most of the world’s hot deserts are located around the same latitude in both the northern and southern hemispheres.

These deserts form as a result of the same large-scale circulations that create the jet streams that provide us with most of our active weather.

Vast amounts of sinking air over the American Southwest, northern Africa, and southwestern Asia keep these regions hot, sunny, and dry for much of the year.

RELATED: How the driest places on Earth can see mammoth flooding rains

But that’s not always the case. Many of the world’s deserts experience an annual monsoon, a short-term shift in prevailing winds that draws moisture over deserts and fuels near-daily chances for heavy rain and thunderstorms.

Monsoonal rains are intense, sometimes producing rainfall rates of 20+ mm per hour. This doesn’t seem like much of a deluge for temperate climates, but desert soils are largely impermeable, so water simply runs off instead of absorbing into the ground.

As a result of those water-repellent soils, monsoon season is often flash flood season across the world’s deserts. The American Southwest is particularly susceptible to flash floods, even dozens of kilometres away from a raging storm where the skies are clear and unassuming.

Flash flood damage in Death Valley, California, in August 2022. (NPS).

Death Valley, California, is no stranger to this phenomenon. The infamous spot saw the world’s hottest temperature of 57°C on July 10, 1913. Unsurprisingly, they only see about 55 mm of rain in an average year.

A vigorous downpour on August 5, 2022, dumped 43 mm of rain over Death Valley National Park in a single day, the location’s wettest day ever recorded. That much rain is tolerable just about anywhere else, but the results are disastrous when such a glut of water falls over the desert soils.

Tremendous flash flooding swept through the region after the deluge, washing out roads and sending rock-filled flood waters gushing across the terrain.

These downpours can fill an arroyo, or a dry river bed, with rushing torrents of water in mere seconds. The floods that fill an arroyo can flow far away from the storm that produced the heavy rainfall, sending a wall of water and debris into areas where the weather is calm and even clear. It’s a terrifying sight—and one that often catches hikers and campers by surprise, sometimes to a tragic end.

If you ever visit a desert region during the monsoon season, pay close attention to local weather forecasts and heed the advice of local officials if they warn that flash flooding is possible.

WATCH: Flash flood tears through arroyo in Santa Fe, New Mexico

Hurricanes are more common than you’d think

Hurricanes and the remnants of hurricanes are relatively common in desert areas. The American Southwest is the common target of remnant storms that move into the region after making landfall in Mexico. These systems are often responsible for the heaviest rains on record in places like southern California and Arizona.

The Arabian Peninsula is also no stranger to ferocious storms swirling in from the Indian Ocean. Cyclones here occasionally track west toward Oman, Yemen, Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates, plowing into the region with destructive winds and prolific rains that flood the dry, sandy landscape.

Cyclone Chapala approaches Yemen on November 2, 2015, with the equivalent strength of a major Category 3 hurricane. (NASA Worldview)

Tropical cyclones are also a common occurrence in Australia, the vast majority of which is covered by rust-tinged deserts. Powerful cyclones frequently spin up off the country’s Indian and Pacific coasts and make landfall, wringing out prolific tropical rains over the vast Australian Outback.

Hurricane-fuelled rains are intense no matter where they sweep ashore. But they’re especially dangerous in the deserts, where they can produce many times the region’s annual rainfall in short order. Some of the cyclones that hit the Arabian Peninsula in recent years have produced more than half a metre of rain.

WATCH: Immense dust storm covers Iraqi town in April 2019

Haboobs are common and potentially lethal

All of the rain falling out of those monsoonal storms can churn out some pretty gusty winds. It’s not uncommon for desert thunderstorms to exceed severe limits, producing wind gusts of 100+ km/h as they bubble and collapse.

Those winds aren’t just a hazard to trees, power lines, and cacti. It’s common for an outflow boundary streaming away from a thunderstorm to gather up immense amounts of dust as they sweep the desert floor, stirring up dust storms that tower more than a kilometre into the sky as they completely shroud entire cities in darkness.

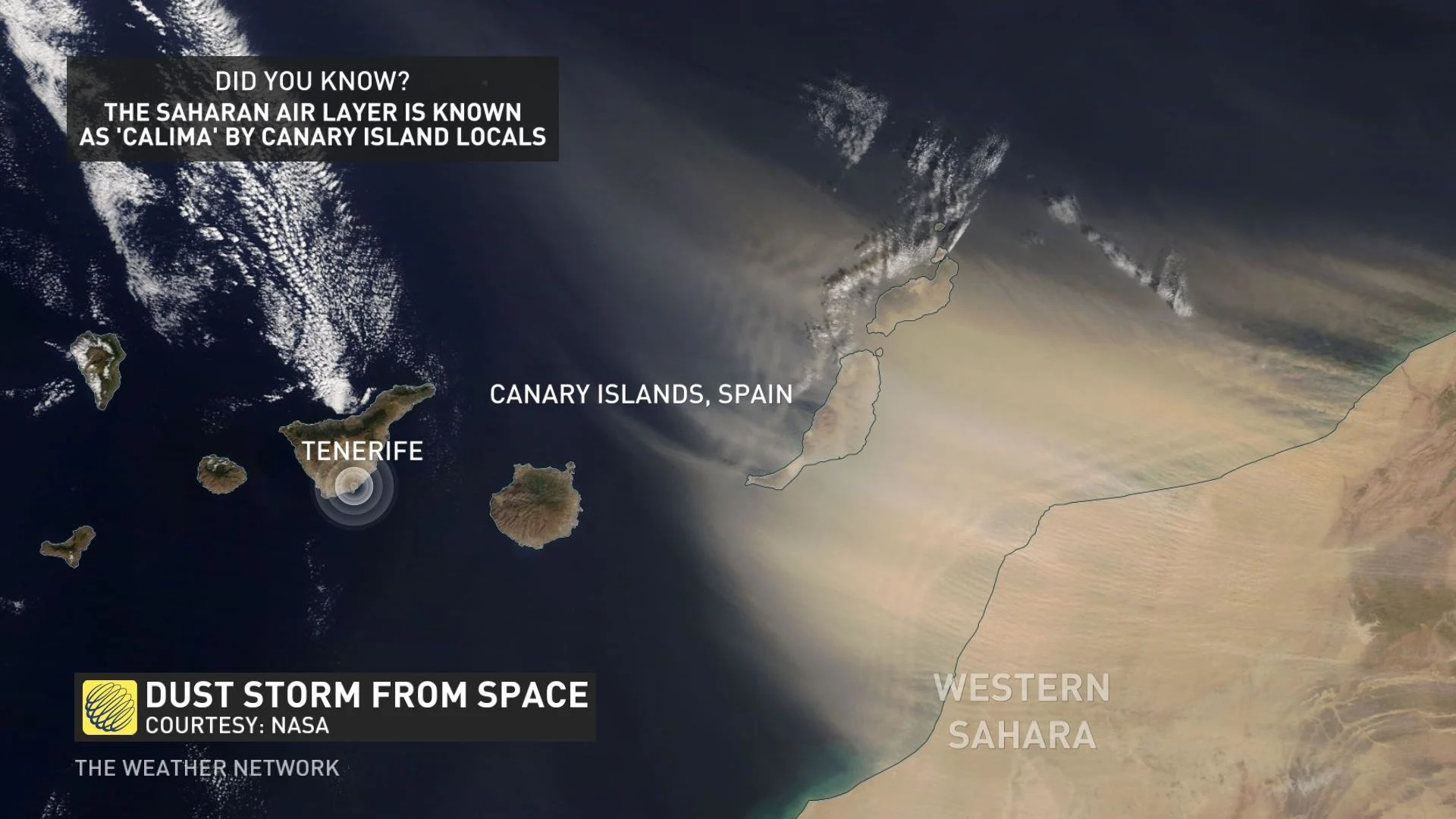

DON'T MISS: Saharan dust can make or break a monstrous Atlantic hurricane

Dust storms, commonly called haboobs when they’re particularly intense, carry their own set of unique hazards. The reduced air quality within a haboob can cause severe respiratory symptoms without adequate masks, a scary prospect for folks living with conditions like asthma.

The sudden drop in visibility can be lethal for motorists who drive into blowing dust. Large pile-up accidents are common during dust storms in places like the American Southwest, sometimes involving dozens of vehicles and high numbers of injuries and fatalities.

Dry heat isn’t as harmless as it sounds

Folks turned off by the endless sizzle of desert summers often hear that it’s a “dry heat,” a lack of humidity that seemingly makes up for the blazing temperatures.

RELATED: Five horrible things extreme heat does to the human body

But that desiccated air isn’t harmless at all. If the air temperature is 45°C, for instance, your body has to work really hard to regulate its internal temperature. You’re going to sweat a great deal in order to cool off.

Sweat readily evaporates off your skin when it’s that dry outside—a process that works too efficiently. Dehydration can set in very quickly in these dry climates, which can allow illnesses like heat exhaustion and heat stroke to set in faster than expected.

Some deserts are the muggiest places on Earth

Deserts aren’t always bathed in a dry heat.

Countries lining the Persian Gulf have to deal with some of Earth’s most inhospitable conditions. Not only do they have to contend with desert heat, with daily highs far exceeding 45°C, but the region’s geography allows humidity to reach tropical levels.

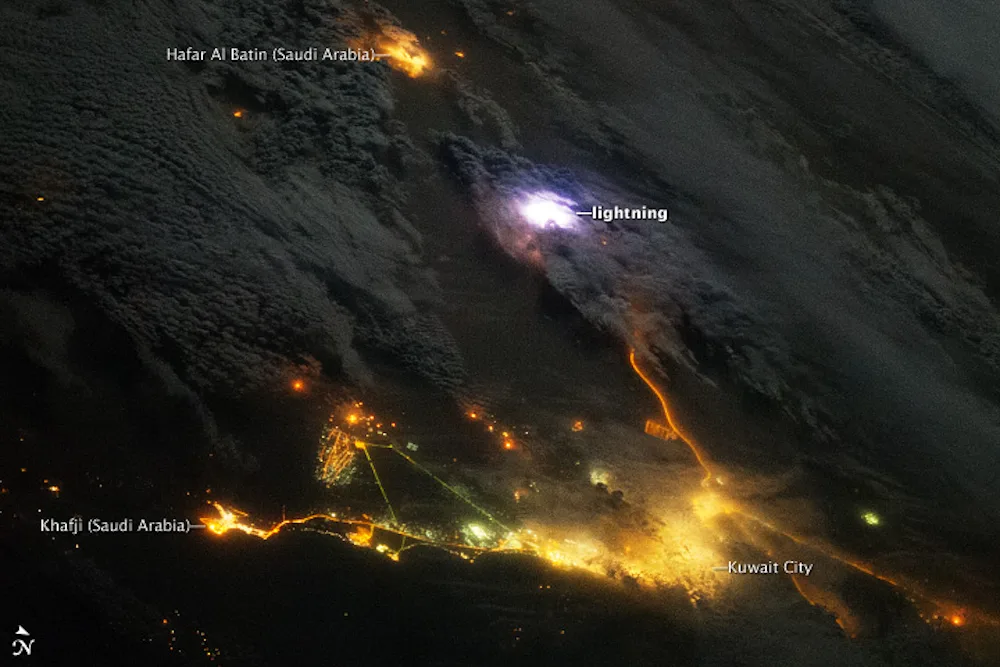

A flash of lightning illuminates a thunderstorm over Kuwait and Saudi Arabia in December 2013, as seen from the International Space Station. (NASA)

Extremely warm water surface temperatures in the Persian Gulf allow the dew point—a measure of moisture in the air, it’s the temperature at which the relative humidity reaches 100 percent—to soar above 32°C, which is far muggier than it gets even in the tropics.

STAY SAFE: How hot is too hot for the human body?

This intense humidity can push the feels-like value in places like the United Arab Emirates and the southern coast of Iran can easily exceed 55 during the heart of the summer.

Dhahran, Saudi Arabia, holds the claim for the highest dew point ever measured, according to NOAA. A high temperature of 42°C with a dew point of 35°C on July 8, 2003, sent the feels-like value that afternoon to an astounding 81—far beyond the ability for humans to survive long without adequate protection.

Header image courtesy of Nick Dunlap via Unsplash.