Deadly differences: The 'Snow Eater' vs the 'Devil Winds'

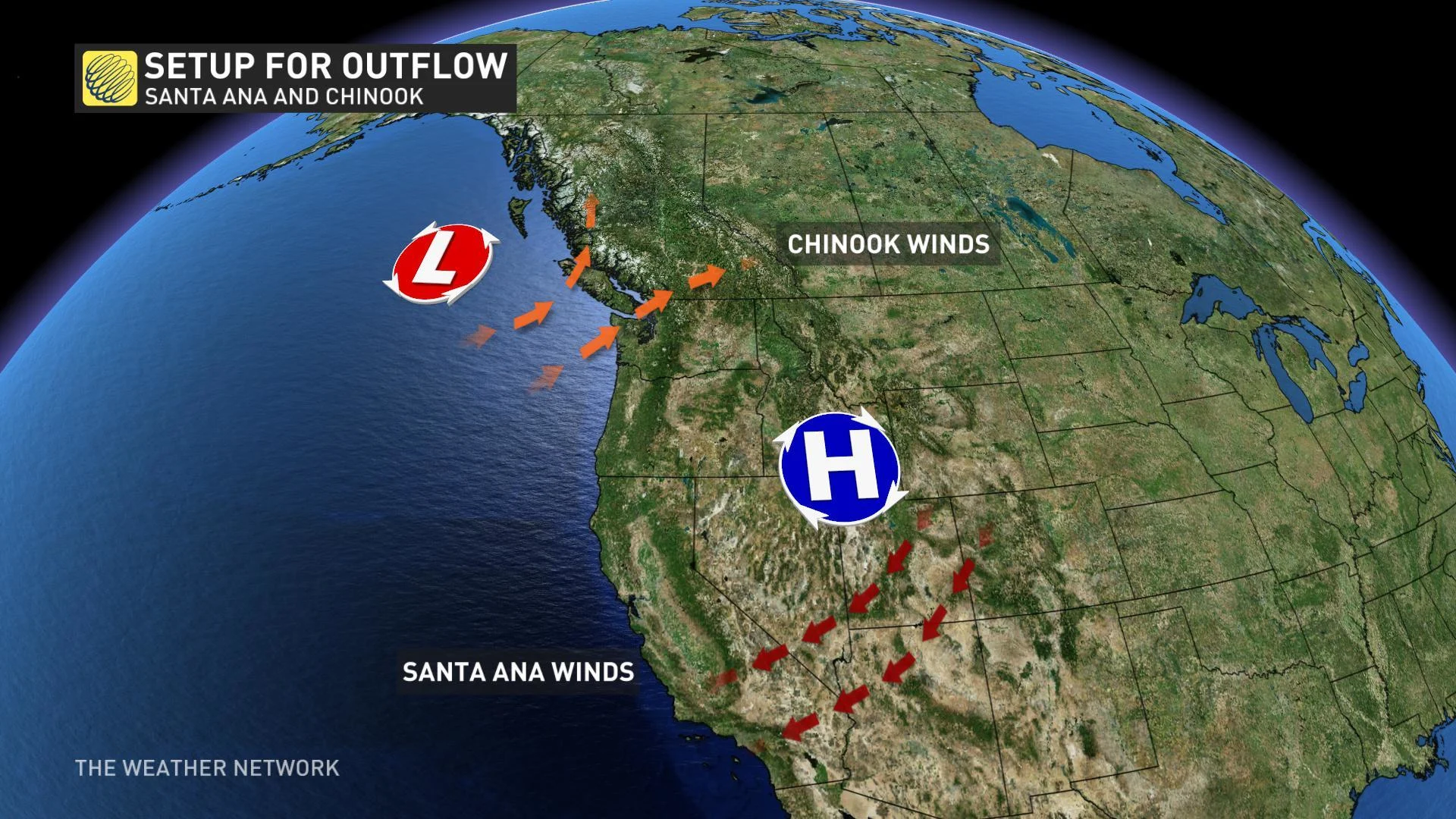

Snow eater and devil wind. As the names people have given them suggest, one of these is generally a lot more welcome than the other when it blows into town. But did you know our familiar Canadian Chinook and the wildfire-fanning Santa Ana winds are born of similar processes? We talk a lot about upsloping and downsloping winds when it comes to the weather here at home, especially across western Canada, where the western mountain ranges play a pivotal role in determining the continent's weather patterns, including the development of Chinooks and Santa Anas. So what makes one a welcome break from winter cold and the other fuel for catastrophic fires?

Like so much in life, the devil (wind) is in the details.

Welcome warm up—The Chinook

The most famous Chinook winds develop along the Front Range of the Rockies, from Alberta down to Colorado. Thanks to the typical winter-time position of the jet stream in North America, the most intense Chinooks frequent southern Alberta, from about Calgary down to central Montana.

These types of Chinook Arc clouds are often associated with the descending air. Image: Ela Thakore, Vulcan, Alta.

SEE ALSO: The difference between steam, snow, and dust devils

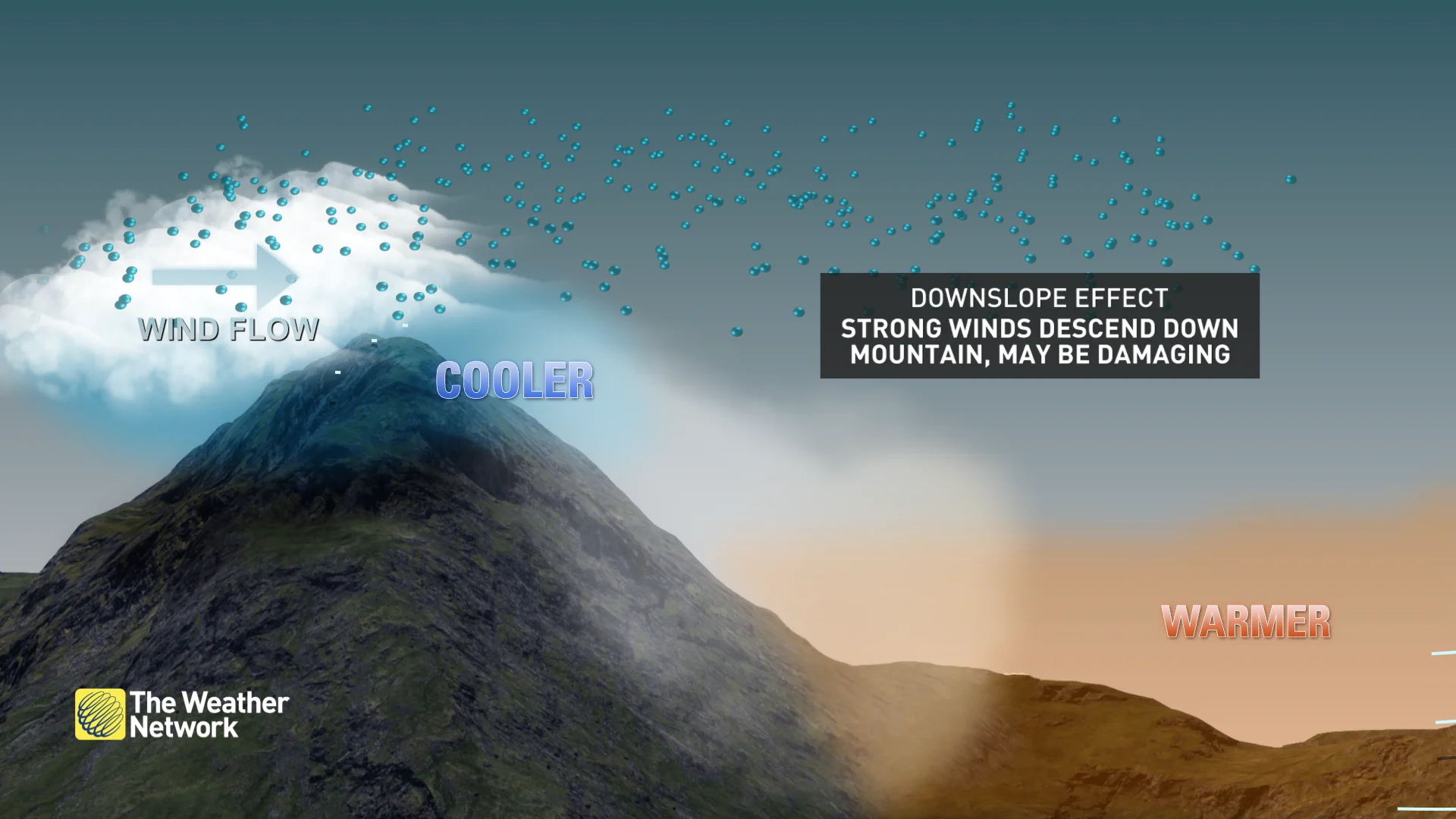

The Chinook is a downslope wind generated when westerly winds travel over the Rockies. They're particularly potent during the cool seasons, when onshore flow into British Columbia sends especially moist air up over the mountains—moisture that then condenses as the air mass rises, falling as rain or snow on the windward side of the mountain chains. As the now-drier air mass sinks on the leeward side of the mountains, it warms. This cycle of rising-condensation-sinking-warming continues until the warm, dry air mass descends from the Rockies and plows through the adjacent western Prairies and U.S. High Plains.

Explainer: Chinook winds (The Weather Network)

These winds can drastically, and abruptly, increase the surface temperature. It's not unusual to see a spike of 20 C (or more) as winds gust in excess of 100 km/h. Calgary's record high temperatures from November to March are all likely associated with Chinook wind events.

DON'T MISS: The Weather Network's hub for wildfire news in Canada

Fanning the flames—The Santa Ana

Like their northern cousins, Santa Ana winds are also downslope winds, but they are generated by high pressure over the U.S. Great Basin and Desert Southwest rather than moist air masses from the Pacific. That inland high pressure produces the pressure gradient between desert and ocean that drives the winds to flow offshore.

While this desert-source air starts out dry, whatever moisture is left in it tends to be wrung out by the same mechanism as we see with the Chinook (albeit travelling in the opposite direction). That means by the time it crashes out into Southern California, we're looking at an air mass with extremely low relative humidity. Couple that with the funnelling effect of passes through the mountain ranges of Southern California, and you're looking at a concentrated blast of hot, dry air into the region.

This is where we get back to those details, specifically timing and terrain.

Santa Ana winds are most common in the autumn—that is, on the tail end of the dry season across California. That means they arise when the terrain and the forests are already dry and the fire danger is already typically on the rise. With the aid of the dry desert winds, already-dry forests and shrubland become tinderboxes in search of a spark. Once that spark is lit, winds as strong as 90 km/h, gusting as high as 150 km/h—and occasionally in excess of 200 km/h—drive the flames to devour the dry chaparral terrain with often staggering speed.