Sunday marks the earliest start to the Fall season in 228 years! Here's why

Summer's final curtain call. Here's a guide to the science behind this phenomenon, some of its most enduring myths, and why this is the earliest fall equinox in over 2 centuries.

September 22 is the Autumnal Equinox for 2024, marking the earliest start to the fall season for the northern hemisphere since 1796.

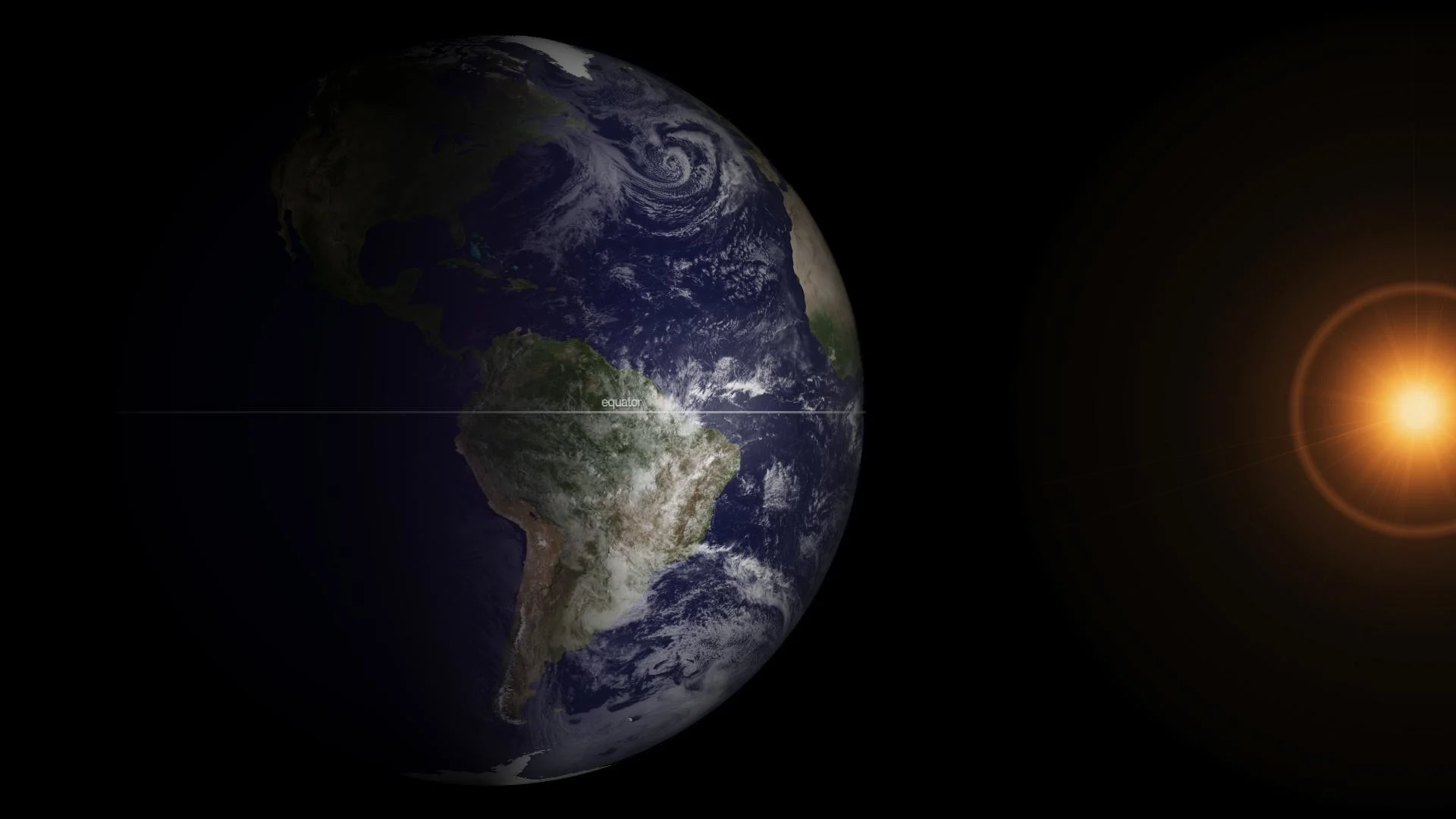

Standing here on Earth's surface, everything may seem perfectly normal with the universe. However, looking at our world from afar, the entire planet is slightly off-kilter.

As Earth follows its elliptical path around the Sun, the planet's rotational axis — the imaginary line that runs through the North and South Poles — is tilted with respect to that path, by roughly 23.4 degrees. Earth doesn't 'wobble' back and forth by that much, mind you. The tilt is constant, such that the North Pole always points roughly towards a bright binary star named Polaris.

This consistent tilt, along with our world's motion around the Sun, are the reasons for our seasons.

Credit: NASA/Scott Sutherland

We don't feel this tilt from here on the surface, since gravity is constantly pulling us towards the planet's core. However, we do see its effects. The most directly noticeable impact is how high the Sun reaches as it arcs across the sky each day throughout the year.

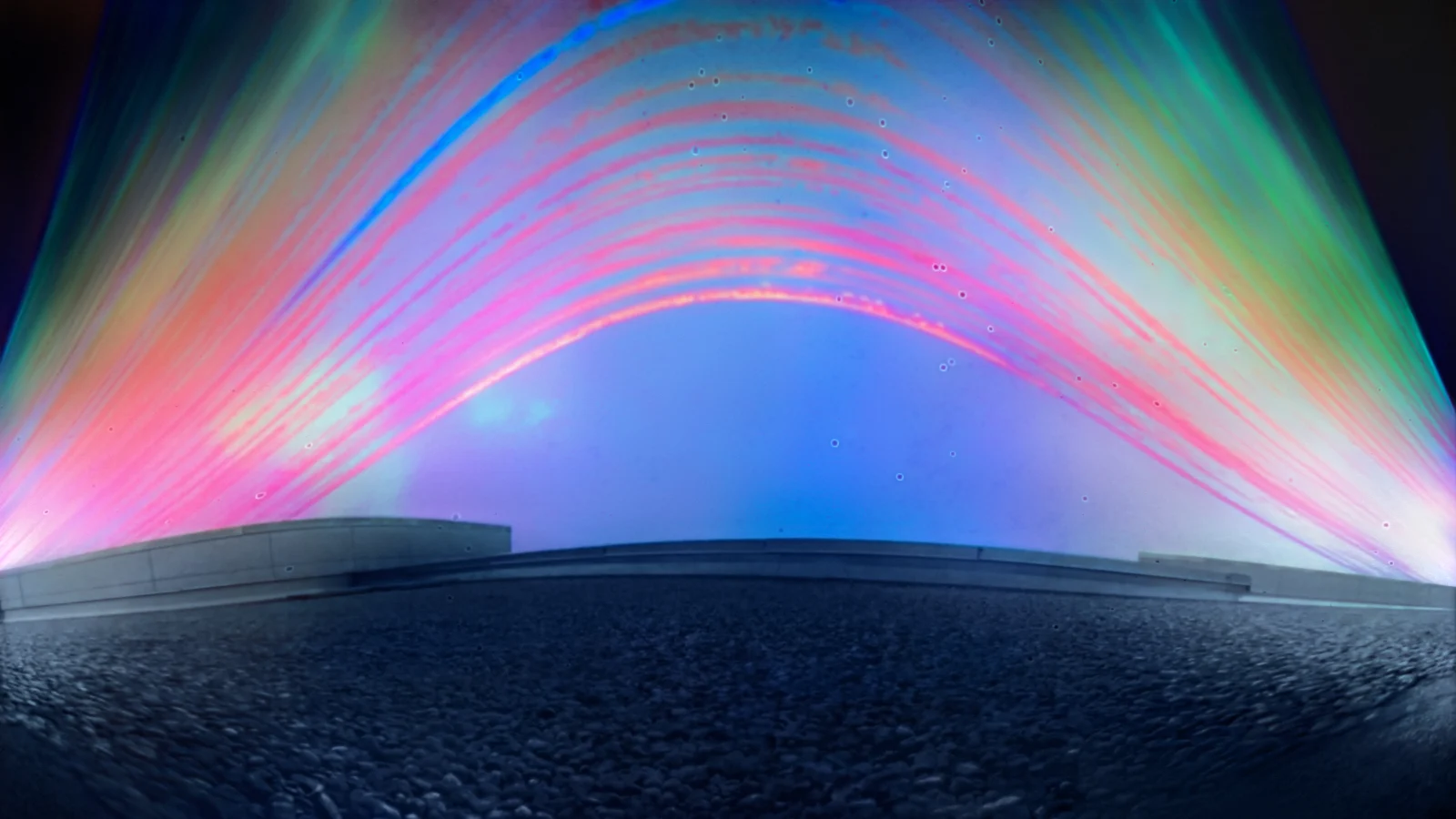

In the 'solargraph' image shown below, each arc across the image is the path the Sun took through the sky, with one arc accounting for each reasonably clear day between June 21 and December 21, 2023. In a single image, then, is revealed how high and how low the Sun reaches in the sky over Oakville, Ontario, Canada, due to the tilt of Earth's axis.

This 'solargraph' image shows the Sun's changing path through the sky from its highest point at Summer Solstice to its lowest point at Winter Solstice, in 2023. The image was achieved using a pinhole camera containing a piece of light-sensitive photographic paper, with a tiny pinhole in the side of the camera focusing sunlight onto the paper's surface each day over the six-month period. (Bret Culp)

While the solstices represent the two extremes in the image, there is one arc around the middle of the swath that was recorded on a day when the Sun lit up both the northern and southern hemispheres of Earth equally. This was the Fall Equinox.

Earliest in 228 years

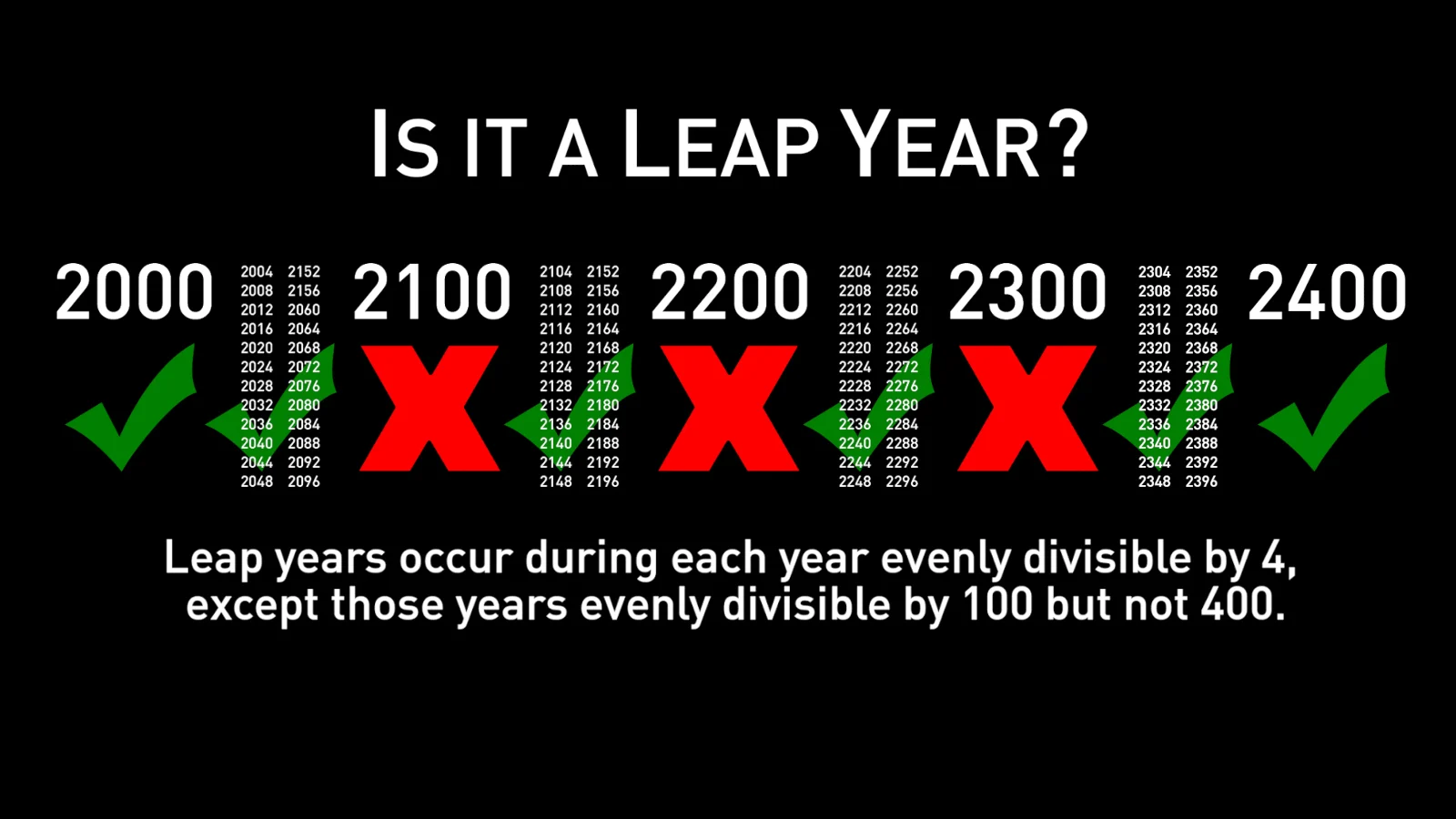

While the equinoxes and solstices happen around the same time each year, their exact day and time are never the same. Partly this is due to Earth taking a slightly different elliptical path around the Sun each year, thus changing the exact time it takes for the planet to complete that orbit by several minutes either way. The rest is because we use a 365-day calendar to track the 365.25 days of time between one spring equinox and the next.

As a result, the roughly six hours of extra time, coupled with our use of leap years, produces a very specific pattern in the timing of the equinoxes and solstices. Each year, for three years in a row, these astronomical milestones occur nearly six hours later than the year before. Then, on the fourth year — specifically the leap year — their timing shifts backwards by roughly 18 hours.

During the last full run of this pattern, fall equinox in 2021 was at 3:21 p.m. EDT on Sep 22. In 2022, it was at 9:03 p.m. EDT on Sep 22, followed by 2:50 a.m. on Sep 23 in 2023. Now, in 2024, it advanced again by nearly six hours to 8:43 a.m. EDT. Instead of being on Sep 23, though, it was pulled back a full 24 hours by the leap year, landing on Sep 22 again.

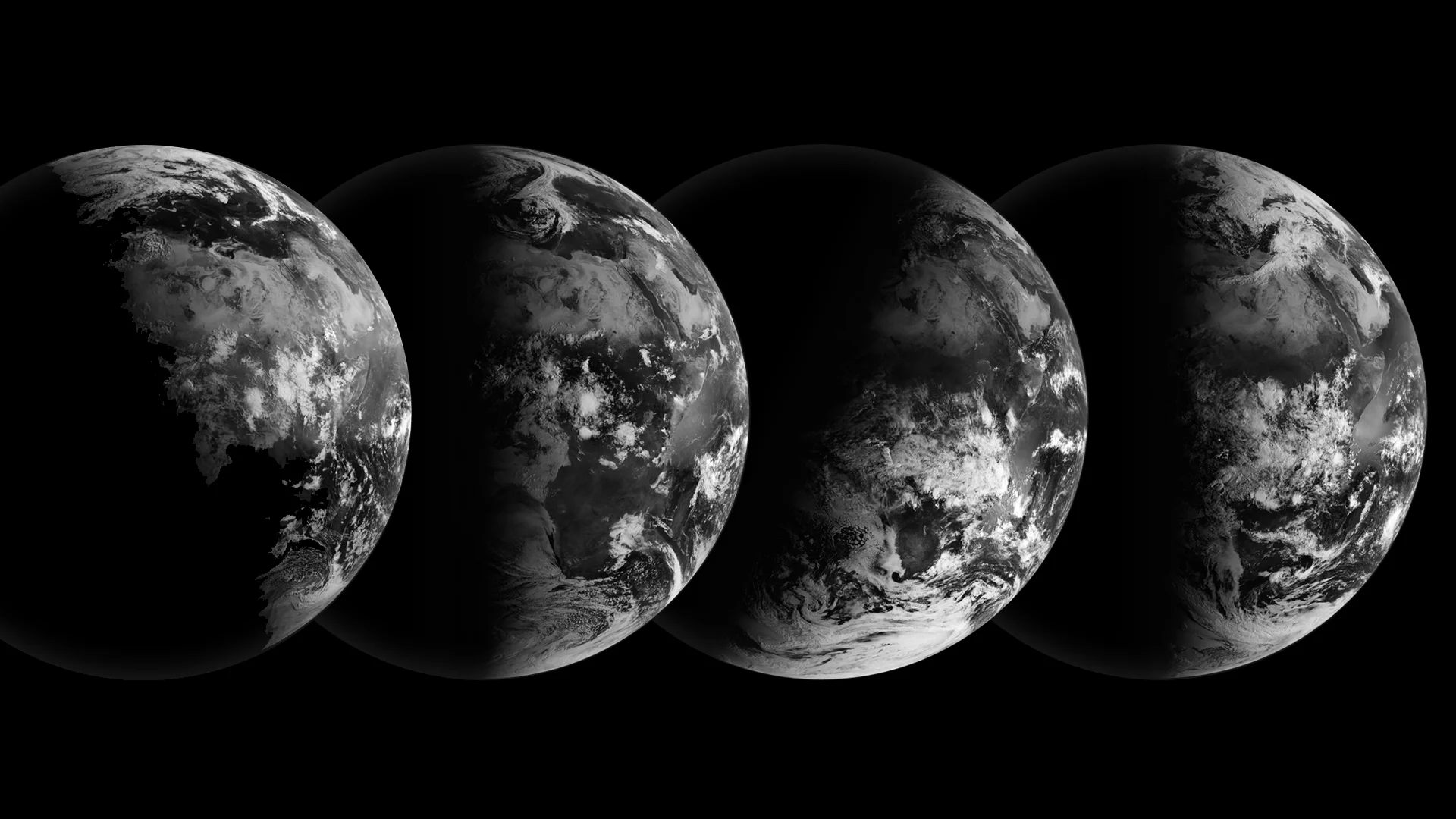

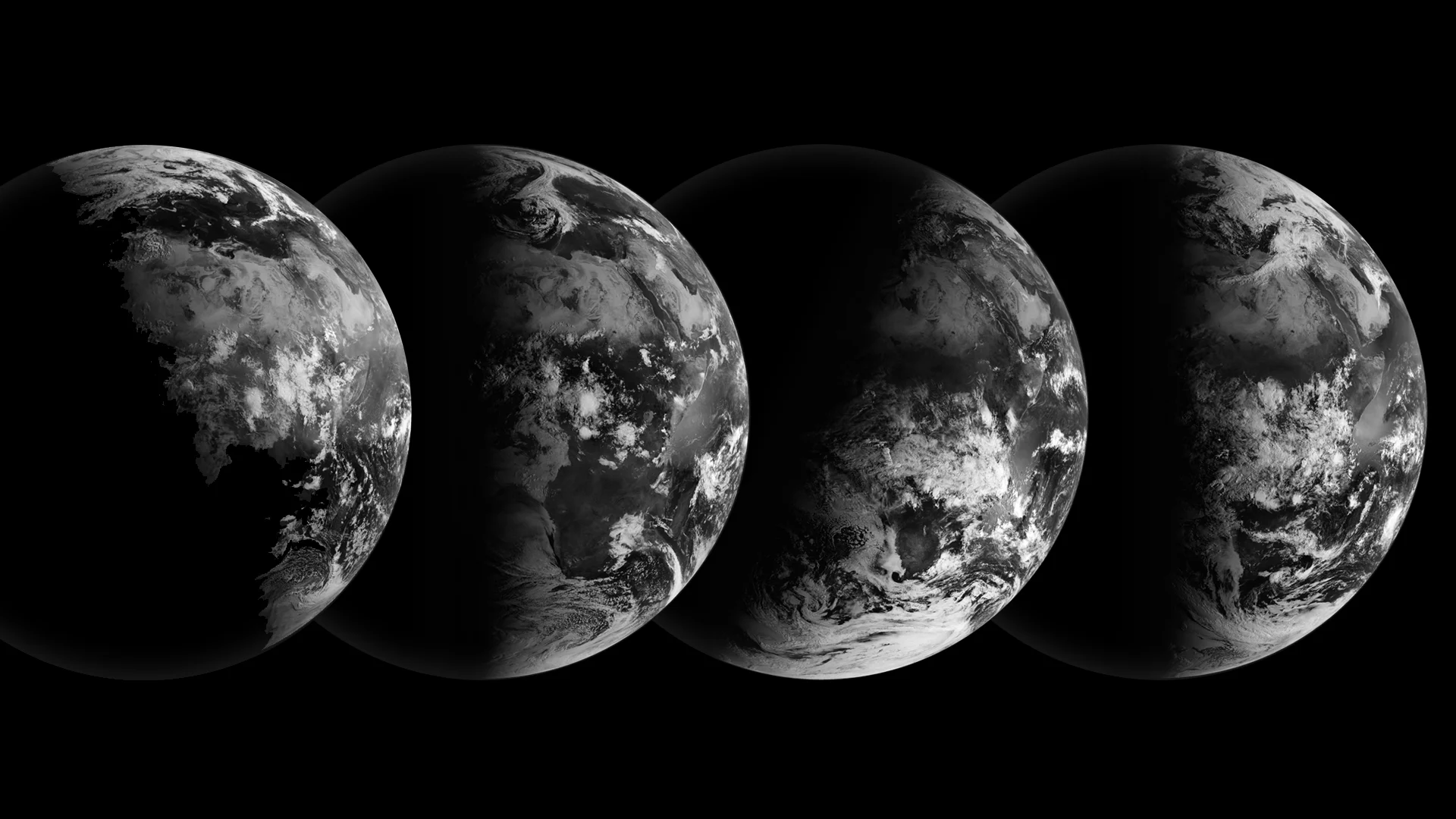

These four views of Earth from satellites in space show our planet, from left to right, during the northern summer solstice, fall equinox, winter solstice, and spring equinox (NASA)

Over the past century or two, on most years, the fall equinox has occurred on the 22nd of September, with the occasional one happening early on the 23rd. However, ever since the year 2000, we've seen an interesting new pattern: each time we have a leap year, the equinoxes and solstices set a new record for the earliest we've seen.

Why? Well, before the year 2000, whenever we've come around to a 'century' year (1800 and 1900, specifically), it hasn't counted as a leap year. Normally, it would, as we can evenly divide those years by 4, like every leap year. However, there's an additional rule for leap years, where we do not count any year that is evenly divisible by 100, but not by 400. This second rule compensates for a bit of extra time that all the other leap years add to the calendar.

When we reached the years 1800 and 1900, the skipped leap year meant that the equinoxes and solstices didn't shift back by 24 hours. Instead, just like in the previous three years, their timing advanced by nearly six hours. As a result, they occurred significantly later than usual, and essentially reset the pattern of these astronomical dates occurring earlier and earlier.

However, we skipped 2000 as a leap year. Therefore, that 'reset' didn't occur, and the equinoxes and solstices have continued to get earlier and earlier with every leap year since.

Now, in 2024, the fall equinox is at 8:43 a.m. EDT on September 22. The last September equinox that was close to that early was at 8:03 a.m., on Sep 22, 1896. However, since Daylight Saving Time wasn't in use then, that 8:03 a.m. is actually equivalent to 9:03 a.m. EDT in 2024, making it later than this year's equinox.

The last fall equinox that was earlier than 2024's was 228 years ago, back on September 22, 1796, when it occurred at 3:06 a.m. local mean time (roughly equivalent to Eastern Standard Time).

This isn't the absolute earliest fall equinox, though. Up until the mid-1700s, due to centuries of counting every fourth year as a leap year, without exception, the timing of these astronomical dates had wandered backwards by about 10 days, with the fall equinox occurring on Sep 12 in 1751.

With the calendar now corrected and us skipping three out of every four 'century' leap years to keep it corrected, we won't see the timing slip back that far again. However, they will continue to get earlier and earlier every fourth year going forward, right up until 2096. That year, the fall equinox will be at 6:56 p.m. EDT on September 21 — the earliest since the calendar reset in 1752.

READ MORE: Watch our seasons go topsy-turvy without leap years

Myths of the Equinox

There are a few urban myths surrounding the equinoxes that make their rounds on the internet each year, no matter how often they're debunked.

1. Balancing act

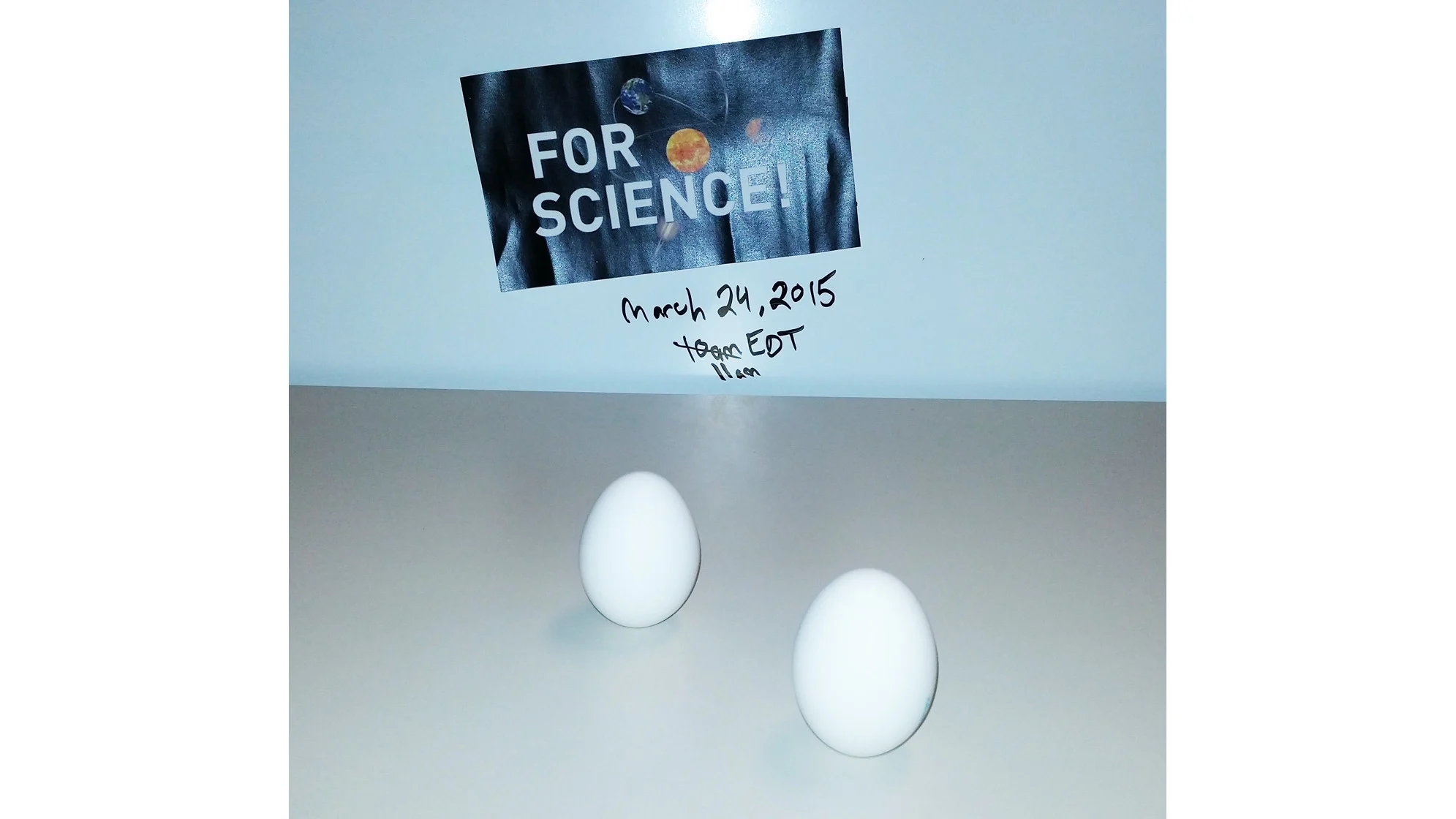

Whenever the equinox is approaching, spring or fall, word spreads that this is the day to perform a "fantastical feat" of egg balancing.

While balancing an egg on its narrow end is challenging at any time, the equinox in no way makes that task easier.

These two eggs were balanced on there ends on March 24, 2015, four days after the equinox. (Scott Sutherland)

The reason for this? Basically, while it's true that every object in the universe tugs on every other object, here on Earth's surface, our planet's gravity completely overwhelms any other gravitational forces we (or eggs we are balancing) might experience.

The Moon's gravity is the next strongest influence, followed by the Sun, and they are the reasons for our ocean tides. However, the tides only occur due to the cumulative effect of these objects simultaneously pulling on each individual molecule in an immense body of water. For something as small as an egg, the gravitational pull of the Moon and Sun is so weak that it has no effect whatsoever.

Only three factors matter in balancing eggs: the stability of the surface you are using, the 'bumpiness' of the eggs being balanced, and the steadiness of your hands.

2. Those crazy days (and nights)

There are two days during the year when night and day are roughly 12 hours long. However, despite the word equinox coming from the Latin words for 'equal' and 'night', those two days do not fall on the equinoxes.

Depending on your latitude, the dates of equal day and night can happen anywhere from a couple of days up to a few weeks before the spring equinox and after the fall equinox. The closer you are to the equator, the bigger the gap is. In southern Canada, in Fall 2024, this date is around the 24th or 25th of September, in Mexico City, it occurs on Sep 28, while in Managua, Nicaragua, it doesn't happen until the 2nd of October.

Anyone at the equator actually never sees equal day and night. The day in Quito, Ecuador, for example, is always about six minutes longer than the night.

A view of the equinox from space, courtesy the GOES geostationary weather satellite. (NOAA)

That may seem unbelievable, but we do this to ourselves simply by how we have defined sunrise and sunset.

'Sunrise' is the exact moment when the edge of the Sun crests the eastern horizon. 'Sunset' is when the Sun completely disappears below the western horizon. Based on that, we are adding several minutes to the length of our day.

To have equal day and night on the equinoxes (and on the equator), we would need to change those definitions, so those two moments were defined by when the Sun is precisely centred on the respective horizon.

3. Shadows stick to us

It's difficult for us to escape from our shadow, even during the equinox.

Occasionally, claims circulate that you will not cast a shadow, even on a sunny day, if you stand on the equator during the equinox. Unfortunately, this takes some precise timing and very specific conditions to even be almost true.

This is due to the equinox occurring at different times of the day. In 2024, for example, the autumnal equinox occurs at 8:43 a.m. EDT. Unless you have some particularly dark clouds overhead at that time, you'd most certainly cast a shadow at that time of day. Looking back to last year, though, it was at 2:50 a.m. EDT, when the only shadow you'd likely cast would be from an overhead street light or maybe a particularly bright Full Moon.

However, what if you picked your location perfectly, so that you are at the exact place on Earth where the equinox happens precisely at noon? In 2024, that would be on the equator, about 80 km west of the Prime Meridian, which would be off the west coast of Africa. Even so, you'd still see your shadow cast on, between, and around your feet. Sorry.